A Patchwork Quilt of Perspectives: Polyphony in Faulkner Eric Lyons

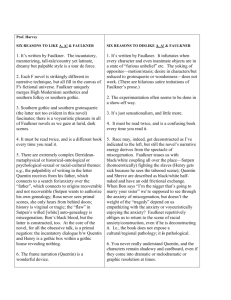

advertisement