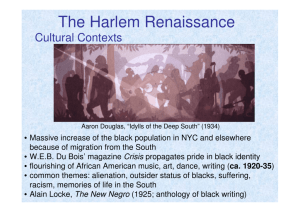

Literature - Washington University in St. Louis

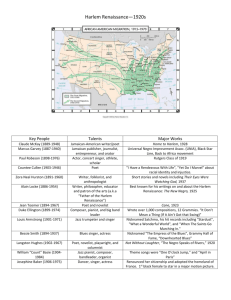

advertisement