Transcendence of traditional melodrama—A brief

advertisement

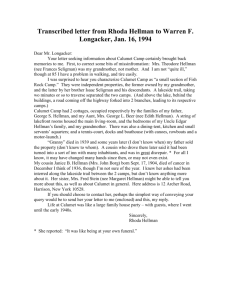

Feb. 2010, Volume 7, No.2 (Serial No.74) Sino-US English Teaching, ISSN 1539-8072, USA Transcendence of traditional melodrama—A brief analysis on Lillian Hellman’s The Little Foxes SUN Jing-bo (School of Foreign Languages, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen 518060, China) Abstract: Lillian Hellman is a leading figure in 20th century American theatre. Due to the intensity of feeling and the general theme of good vs. evil, her plays are tagged with “melodrama”. However, by examining one of her masterpieces The Little Foxes, it is revealed that Lillian Hellman transcends the confines of traditional melodrama by combining the complexity of real life into the pretense of representation, thus making her play forcefully believable. Key words: melodrama; transcendence; The Little Foxes; realism 1. Introduction Lillian Hellman was among the most famous playwrights of 20th century American theatre and was the first woman playwright who enjoyed great popularity and reputation in the male-dominant American dramatic literature. All through her life, Lillian Hellman wrote eight original plays, among which The Children’s Hour (1934) and The Little Foxes (1939) earned her great successes in American theatre and the lasting honor in her professional life. In personal life, she pursued her ideals and adhered to her beliefs: She was also an activist on political stage and an advocate of women’s social rights. Despite the high compliment and honor she receives, Lillian Hellman’s works are liable to be tagged as “melodrama”. Melodrama was a popular form of drama, which almost dominated the stage of 19th century. In traditional sense, melodrama refers to a sensational, romantic play full of impossible events where the good are always rewarded and the wicked always punished. The modern sense of melodrama is “an emotionally exaggerated conflict of pure maidenhood and scheming villainy in a plot full of suspense” (Baldick, 2000, p. 131). Due to the intensity of feeling and the general theme of good vs. evil, Lillian Hellman’s plays are tagged with “melodrama”. However, when we have a close study on her works, we may find that Hellman’s plays are not to be confined to melodrama. They transcend the concept coming close to life itself. Although all of her stage pieces carry her strong moral convictions in the constant struggle between good and evil, fortunately, in Hellman’s best plays, the characters’ talk and move in a believably realistic fashion and the neat structure of well-made play is disrupted by a sense of life’s complexity. Thus, the danger of drawing simplistic lines between the bad and the good is avoided. And the illusion of real life on stage is well maintained. The Little Foxes is one of the best examples of how Lillian Hellman combines pretense of representation and dramatic realism into one play. Focused on the social background, the characterization and the plot development of The Little Foxes, the following part examines how Hellman accomplishes the combination of the employment and the transcendence of melodrama in the play. SUN Jing-bo, lecturer of School of Foreign Languages, Shenzhen University; research field: American literature. 59 Transcendence of traditional melodrama—A brief analysis on Lillian Hellman’s The Little Foxes 2. Realistic background Set in the south at the turn of 20th century, The Little Foxes displays how a family is torn apart by greed and desire. Brothers Ben and Oscar Hubbard plan to establish a mill in their town and need $75,000 for the venture. They ask help from their sister Regina Giddens, who is married to Horace, the president of the local band. Horace, who has only a short time to live, refuses to become involved. Oscar’s Son Leo, working at the bank, steals bonds to help his father. Horace discovers the theft but will not prosecute the brothers. He makes a new will in which Regina will receive only the exact amount of the theft. Horace dies and Regina blackmails her brothers into assigning her a 75 percent interest in the mill. Alexandra, her daughter, discovers her mother’s treachery and greed, and leaves her home forever. The turning of the 20th century witnessed the United States’ shift from a rural to an urban society. The forces of modernization had a strong impact on people’s ideas and way of life, and the impact was extremely fierce on the south. During this period, Americans were experiencing “a bewildering kaleidoscope of events and pathology of uncontrolled expansion; the rise of the New South; secularized religion; an increasingly mechanized and compartmentalized daily life; the advent of the ‘New Woman’….” (Frick, 1999, p. 196). All these are well depicted in The Little Foxes—the time, the land and the incarnation of the “New Woman” Regina. Thus, we can safely get to the point that the background of The Little Foxes derives from the realistic society. The acceptability and credibility of Hellman’s central characters also has some bearing on the social background. These people exist in a historical period when material fortunes are based on merciless capitalizing on the opportunity at hand, regardless of consequences. They live in a locale where polite society is still torn apart by a desire to cling to old beliefs and by an inability to recognize the kind of change that must come. If the Hubbards do not exactly represent larger world, at least Hellman successfully creates a realistic, mercenary southern aristocratic family, and more importantly, reveals the situation of human beings deprived of self-respect and consciences, driven by desire and greed, and unable to oppose the evil. 3. Complexity in characterization Part of the definition of melodrama is that the stereotypical characters in melodrama are held to be all good or all bad, and are immediately recognized by their costumes and demeanor. However, this is not totally the case in The Little Foxes. Like in the real life, there is no clear and absolute distinguishing line between evil and good. The characters in the play have more qualities than just surface evil to define them. Regina, for instance, carries understandable human qualities as a woman—a beautiful, gracious and dignified hostess, seeking elegance, social position and public respect. Born into a southern aristocrat family, Regina is the only daughter of the Hubbards. But her father considers only sons as legal heirs, and as a result, her avaricious brothers Benjamin and Oscar inherit the entire legacy and become independently wealthy, while she must trade her marriage to Horace Giddens in return for the financial holdings he will bring to her. In struggling for freedom and wealth within the confines of the social conventions in the American south of the early 20th century, she must sacrifice love in order to satisfy her ambition for power and influence. From her maidenhood, she makes constant efforts to escape from the suffocating family and the dreary and tedious life in the south, fight against the Patriarchal constraint by her father and brothers, and pursue her individual independence of wealth and spirit as well. In this sense, Regina is the incarnation of the “New Woman” of independence and strong will. Although her desire to get money can not justify her means, Regina is a 60 Transcendence of traditional melodrama—A brief analysis on Lillian Hellman’s The Little Foxes charming woman with a complexity of qualities of boldness, ruthlessness, resolution and independent. The melodramatic stereotypical evaluation of all bad on Regina obviously does not reach the essence of the character. And the version to interpret Regina only as a greedy bad woman is too simplified, and in no sense, Lillian Hellman depicts this character as all evil. In fact, Regina herself is a victim of the society conventions. Oscar’s wife Birdie, seeming a minor character in the play, in fact, is dramatically important. Contrary to Regina, Birdie is a kind, obedient and devoted wife, but in no sense, she is happier than Regina. Actually, she lives a miserable life and happiness is a faraway dream that she can never achieve. Hellman’s craftsmanship is also embodied in this character: Readers accept Birdie as a pitiful woman, but agree that Birdie has well-expounded reasons for what she has become. Her life itself is a warning for Alexandra. It is Birdie’s ineffectual attempts to stop the happening evil and her failing to own dignity and freedom that prevent Alexandra from living a duplicate life of auntie. The closing of The Little Foxes is worthy of more attention. Regina probably wins over her brothers, but loses her daughter Alexandra, whom she has dictated all these years. Actually, throughout the play, Hellman utilizes the development of the character of Alexandra to help parallel the realization of the evil and greed within the family. Alexandra is perhaps the only innocent family member left in the Hubbard clan. After realizing her mother’s real motive and the truth, she determines to leave the house with a young man named David Hewitt, who provides her with love and all the moral support. Alexandra’s revolt is best proclaimed by the final words of the play, “Are you afraid, Mama?” (Hellman, 1979, p. 225). This quote alone foreshadows Alexandra’s breaking away from the family to live a life of truth and happiness of her own and also predicts her mother’s perpetual loneliness despite her financial triumph. Hellman divides the characters of her book into the evil and innocent. The innocent not being able to stop the evil and only standing by and watching it happen. The black maid Addie’s remark sums up the play’s moral: “Well, there are people who eat the earth and eat all the people on it like in the Bible with the locusts. Then there are people who stand around and watch them eat it. Sometimes I think it is not right to stand and watch them do it” (Hellman, 1979, p. 205). Overall, Hellman’s play is a tremendous success in developing a set of characters, who falsely show love to each other in order to help obtain riches and powers within each of their own lives. This brilliant show of intense familial greed illustrates how selfish desires can lead to the breakdown of not only a family, but each member within it. 4. The credibility of the plot In 19th century melodramas, characters development is generally not a focus of the form. The plays are driven by contrived plot and playwrights often have to manipulate the logic of the plot to bring about the happy ending. As Sarah J. Blackstone points, “Often defined as plays on serious subjects with happy endings, melodramas are thought to employ the device of poetic justice, where the good are rewarded and the evil punished on a scale commensurate with their actions” (Murphy, 1999, pp. 21-22). However, the justice implied in traditional melodrama does not occur in The Little Foxes. The greatest force of good is Horace Giddens, but in order to achieve a kind of justice he must play by the same vicious rules, and he dies before all the injustices can be corrected. Although Regina triumphs financially, she suffers from emotional alienation. The play has no definitive ending. There is triumph and defeat on both sides; nobody emerges on top. Lillian Hellman successfully 61 Transcendence of traditional melodrama—A brief analysis on Lillian Hellman’s The Little Foxes avoids falling into traditional melodramatic frame and designs the plot convincingly. The arrangement of plot is based on the structure of the play. The Little Foxes is well-organized. The entire first act serves as an exposition, revealing the past naturally and unobtrusively throughout the opening dialogue. Moreover, the mentality of the Hubbards is demonstrated thoroughly before readers’ eyes. In front of their guest, the outsider Marshall, the vicious Hubbard clan displays their ignorance, hypocrisy and greed; Marshall serves as a credible catalyst, bringing out details the audience must know. The second act is the full development and deepening of the plot. The absence of Horace in Act One leaves his attitude unknown and thus the appearance of Horace in this act becomes the focus. The tension between Regina and Horace is raised with the development of the plot. Act Three is the climax and denouement. Once the background is established, the ruthless infighting of Ben and Oscar and their black mailing of Leo evolve from realistically credible premises. This does not mean that Hellman does not use some vivid melodramatic scenes. The heart attack, for instance, is a harrowing event of pure melodrama from the start of the argument on to the broken bottle as Horace collapses on the stairs. In brief, a play contains chains of events. The control of the rhythm of action is where the art of drama lies. The good management of the rhythm of tension and the establishment of the credibility in The Little Foxes reveal Hellman’s extraordinary craft as a playwright. 5. Conclusion As is known, the nature of a play is presentation, which usually involves more suspense, tension or conflict than other literary genres. Therefore, it is very high demanding for the playwright to bring the sense of realism to spectators. Hellman’s ability to create absorbing and convincing plays and at the same time rehabilitate the melodramatic mode to good advantage in her plays makes her fascinating till today. The Little Foxes vividly represents the degeneration of a new southern aristocratic family which provides a snapshot of the pragmatic and utilitarian society of the American South at the turn of the 20th century. From the analysis above, we can draw to a more moderate view that melodrama is compatible with dramatic realism. Lillian Hellman is a master of it and her works offer good examples of combining the traditional melodramatic elements with social and dramatic realism, thus accomplishing the transcendence of traditional melodrama. References: Baldick, C.. (Ed.). 2000. Oxford concise dictionary of literary terms. Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press. Frick, J.. 1999. A changing theatre: New York and beyond. In: Wilmeth, Don B. & Bigsby, C.. (Eds.). The Cambridge history of American theatre yolume II 1870-1945. New York: Cambridge University Press. Hellman, L.. 1979. Six plays by Lillian Hellman. New York: Vintage Books. Murphy, B.. 1999. The Cambridge companion to American women playwrights. In: Blackstone, S. J.. (Ed.). Women writing melodrama. New York: Cambridge University Press. (Edited by Cathy and Sunny) 62