From Private to Public: Creating a Domestic Violence Community

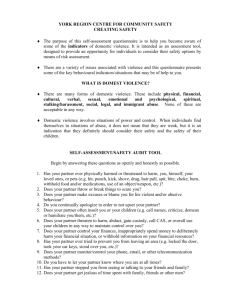

advertisement