Cattle Marketing - Beef Quality Assurance Program

advertisement

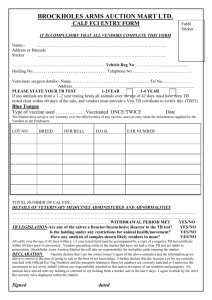

Cattle Marketing M arketing means getting reasonable value for the size, weight, number, type and condition of cattle sold. Some factors affecting these determinants of value are the subject of this chapter. O Source & Age Verified Cattle Marketing Programs ne of the hottest value added topics in our industry involves Source and Age Verified Cattle. With all the interest and buzz circling around these opportunities, it’s no surprise that there is also a growing amount of confusion about what actually makes up a Source and Age Verified animal. Many producers have already been approached by packers, feeders and/or buyers requesting that they or their consignees complete a verification form or affidavit in line with their source and/or age verification requirements. Many of these forms are part of a set of programs approved by USDA that will qualify calves to be marketed as beef for the Japanese marketplace, while others are just purely a paper affidavit with no export affiliation whatsoever. The most important thing to understand is that just because a producer has completed an affidavit, those calves may not be eligible to be sold as beef for the Japanese market. To start clearing up some of the confusion surrounding all of these different forms let’s begin with a series of definitions. Beef Export Verification Program (BEV) A BEV is a series of product requirements that the USDA and an export market (exampleJapan) agree upon and demand of any supplier wishing to export beef into that country’s marketplace. The supplier must have in place, or be a part of a USDA-approved Quality Systems Assessment (QSA) program or a Process Verified Program (PVP) that meets all of the BEV requirements. Eligible beef products must be derived from cattle that are 20 months of age or younger at the time of harvest. Cattle must be individually identified and traceable back to the ranch of origin. (Note – Neither Japan nor USDA specify visual vs. electronic ID – so long as each calf is uniquely and individually identified and that identifier matches all records. Individual programs may have specific tagging requirements.) The records for each calf must indicate either the actual date of birth of each individual calf being sold; or if the producer has a group of calves born in the same calving season each calf may be identified with the actual date of birth of the oldest calf born in the group. Example – A producer has 20 calves born between Feb. 20 and March 20, he has the option of assigning each calf with its actual individual birth date—or if the oldest calf was born on Feb. 20, 2005, all 20 calves would then be assigned the birth date of Feb. 20, 2005. Quality Systems Assessment Program (QSA) Any packer, feedlot, auction market, producer, animal health company, or other related company or group can follow the USDA QSA guidelines. If approved, they can offer a QSA program under which cattle can be enrolled to qualify for Japanese export. Each program may have unique features but the basic elements outlined by USDA will require the producer to identify animals, document birth dates and have a written management system. To date there are 43 approved QSA programs that have been granted the right by USDA to begin qualifying cattle for Japanese export. A list of programs approved and audited by USDA is available online at www.ams.usda.gov/lsg/arc/qsap.htm. Only the cow-calf producer can enroll a calf in a QSA program and all animals must have been enrolled by an approved QSA prior to being sold in order to qualify for Japanese export. These programs are accepting responsibility for each producer’s management records validating the age and source verification claims. To protect the integrity of the program, USDA and each of the approved programs will be required to do regular audits of program and producer records to confirm that all records are in place back to the herd of origin, validating the birth and source info for individual calves. Process Verified Program (PVP) The PVP is similar in design to the QSA programs with the exception that the PVP also makes claims and audits all management claims made by the program. Example – A PVP program may verify and audit only source and age info or it may also include all natural claims, preconditioned claims, etc. To date there are 23 USDA-approved PVPs that have followed the approval process and been granted the right by USDA to begin qualifying cattle as Process Verified. A list of programs is available online at http://processverified.usda.gov. What does it all mean? USDA and in this case, the Japanese, have laid down a set of requirements that our beef and edible beef by-products must meet in order to be exported. Our government and the Japanese government aren’t concerned with any product attributes other than how old the calf was when it was harvested and that each individual animal being harvested for export can be traced back to the ranch of origin. If you’re asked to complete a marketing affidavit on cattle you need to make sure you know what you are signing. Talk to your buyers and ask them to clarify what they’re wanting to accomplish. QSA and PVP programs may be a great opportunity for many producers, but if consignors are not already enrolled in a QSA or PVP program the cattle CAN NOT be represented as being eligible for export to Japan. If consignors have completed an affidavit and have records on hand to validate the claims being made then they can be represented at sale time as being simply Source and Age Verified – but again, this does not mean they are qualified for export to Japan. Participation in a QSA or PVP or even completing a general Source and Age Verification affidavit is absolutely voluntary. It is a value-added opportunity for everyone in the marketing chain. – Adapted from the Livestock Marketing Association website http://www.lmaweb.com/member/QSA/qsa.html. Cattle Marketing (cont.) Market Timing 550 lb Steer Monthly Seasonal Index 110.00 Monthly Seasonal Index 108.00 106.00 104.00 102.00 100.00 98.00 96.00 94.00 92.00 Last 5 yr A beef producer’s ultimate economic role is to convert low-value or unmarketable forage resources into a quality protein product. With foragedriven production systems, most cows calve in the spring. Weaning and selling those calves in the fall causes a supply bulge that results in lower calf prices in the fall. See figure to the left—Feeder Cattle Seasonal Index price relationships. Last 10 yr While every year will have its own price pattern, fed cattle prices are Figure 3. Monthly Seasonal Price Index for 500-599 lb. Steers in Nebraska, 1996-2005. usually highest in March, averaging about 8% above the annual average. Heavy sales of feeder calves tends to depress prices in the fall. Thus prices in August, September, October, and November tend to be about 5% below the annual average price. 90.00 JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC Nobody really knows when the variations in cattle numbers will affect cattle prices, or by how much. Anybody who has a guess can argue the point by using some previous cycle as evidence. Cow Marketing Few price graphs show opportunity in the marketplace better than the seasonal slaughter cow price data. These data for utilSeasonal Cow Prices—1997-2006 (USDA) ity slaughter cows indicate that the increase in price from November to March of the next year averaged about $6.00/cwt since 1997, equivalent to an increase of about 14%. This equates to about $72/head for a 1,200 lb cow. Since most market cows in the U.S. are sold between October and January, the marketplace is flooded and prices are lowest at that time. When a cow is determined “open” at preg-check we want to get rid of her as soon as possible. She’s no longer considered a “money-maker,” but rather a “money-taker.” The quicker she can be sold the sooner we get her out of our hair and the less money we throw away supporting her. This is a true and logical argument, but it bypasses an opportunity in the marketplace due to seasonal price patterns.—Jason Ahola, BQA Coordinator, PH.D, University of Idaho. Price Makers Within a sale period, calf weight probably affects price more than anything else. Generally, lighter calves bring more money/lb. than heavier calves. If, for example, 1,200-lb. slaughter steers were bringing $70/cwt., 800-lb. steers would be worth about $80/cwt.; 500-lb steers would be bringing over $90/cwt. These example price relationships are based on corn being "normally" priced. In years when corn is high priced, feedlot operators prefer to buy “weight” rather than feed it on, so the price of heavier cattle improves, relative to lighter feeders. In a recent year when corn was at a record high, slaughter, stocker, and feeder steers were selling within a $5/cwt. spread. Conversely, cheap corn increases the price of lightweight calves relative to heavier feeders. Uniformity, Quality, and Volume Feedlot operators want calves that will gain predictably in the feedlot. So, buyers will frequently pay a premium for cattle that are uniform. Uniformity begins with the cow herd and the type of bull used. A short breeding season is also an important aid in producing calves that are similar in age and weight. Markets are usually topped by uniform calves grouped into truckload lots (48,000-50,000 lbs.) of steers or heifers. However, most owners of small herds cannot assemble truckload lots and so must look for other ways of selling their calves. Some collaborate with other owners of small herds with similar breeding, attempting to make it easier for buyers to assemble loads of similar calves, thereby improving price per pound. Most auction markets do a very good job of grouping calves or promoting special sales for calves that have been treated similarly. They offer a variety of programs featuring different health and weaning regimes. Cattle Marketing (cont.) Feeder Calf Grades The Agricultural Marketing Act of 1946 originally mandated the standards for feeder calf grades. Changes were made to the grading standards for live feeder cattle in October 2000. They offer a valuable tool for marketing of cattle and calves and certify the grades used to make contracts for cattle on the futures market. The grade of feeder cattle is determined by evaluating three general value-determining characteristics: Frame size, thickness, and thriftiness. Frame size is a skeletal measurement that takes into consideration height and body length in Steers Heifers relation to age. Thickness refers to the development of the individual animal's muscling in Frame size Estimated harvest weight lbs. relation to its skeletal size. Thriftiness is an appraisal of the apparent health of the animal Small.... 1100 1000 and its ability to grow and fatten normally. Medium… Large… 1100-1250 1000-1150 Frame size standards for thrifty feeder cattle are assigned one of three marks, L (large frame), M >1250 >1150 (medium frame), and S (small frame). Largeframe steers and heifers would be expected to reach a U.S. Choice carcass grade at Yield Grade 3 (about 0.5 inches of fat at the 12th rib) at a weight heavier than 1,250 pounds. The chart above shows the other weight/frame size relationships for both steers and heifers. The thickness (muscling) grades range from Number 1 to 4. “Inferior” cattle are unthrifty and are not expected to perform normally in their present state and include those that are “double muscled.” Inferior cattle can have any combination of thickness and frame size. Therefore, where we have had only four grades or so to concern ourselves with in the past, we now have 13. They are L1, L2, L3, L4, M1, M2, M3, M4, S1, S2, S3, S4, and Inferior. This will give potential buyers an even clearer picture of the calves offered for sale. Producers and buyers alike will benefit as the entire beef industry looks to improve the quality and consistency of the product that eventually finds its way to our dinner table. Shrink and Its Meaning Shrink (weight loss) in cattle results from a loss of gut fill and/or tissue loss. Consequently, both buyers and sellers are concerned about shrink, especially since cattle that have undergone excessive shrink are also more likely to get sick. Pasture weight is greater than market or delivery weight. Differences in these amounts depend on time, distance, previous fill and other stresses associated with the marketing process. Recovery from shrink requires anywhere from five to 30 days. Buyers frequently want sellers to compensate for shrink by offering a 2% to 4% discount, or "pencil shrink," on direct sale bids. Buyers know that shrink is inevitable and that higher prices per pound can be offered for "shrunk" cattle. Sellers should be sure that calves are not allowed to shrink excessively before weighing so as to avoid paying for both a pencil shrink and a considerable actual shrink. For example, sellers should take care that calves are not left overnight without feed or water. Time and Distance Primary factors that affect gross shrink are time and distance traveled. Studies indicate that when water and feed are unavailable, cattle shrink about 1% per hour for the first three to four hours—and about .25% per hour for the next eight to 10 hours. Amount of Fill Affects Degree of Shrink Cattle normally have more gut fill on lush grass, silage, or haylage rations than on hay or high-concentrate feedlot rations. Ensuring calves are weaned and on a hay-grain or conditioning diet will result in less shrink than shipping them directly off grass and milk. Calves sold directly off their dams suffer additional stress because they are not accustomed to eating dry feed and drinking water from unfamiliar sources. Handling and Shipping When cattle are handled as quietly as possible and shipped directly from the farm to their final destination in minimum time, both seller and buyer For more information, go to the benefit. Weight loss, stress, and cost to regain pay weight National Beef Quality Assurance are minimized. Guide for Cattle Transportation: www.tbqa.org Dos and Don’ts for Feeder Calf Producers As you manage your cattle during transfer of owner, follow these tips: • Make sure hauling and holding times are kept to a minimum. • Don’t keep calves off feed and water before shipment; maintain them on their regular diet. • Don’t overfill before shipment. • Handle calves quietly, carefully, and slowly during sorting, loading, and hauling to minimize stress. • Make every effort not to move the calves during periods of heat stress.