On Justifying Punishment: The Discrepancy

advertisement

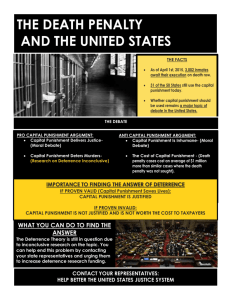

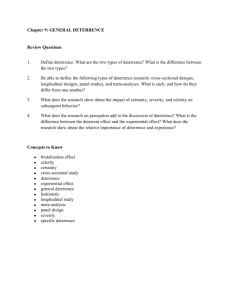

Soc Just Res DOI 10.1007/s11211-008-0068-x On Justifying Punishment: The Discrepancy Between Words and Actions Kevin M. Carlsmith ! Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2008 Abstract This article reveals a discrepancy between the actual and stated motives for punishment. Two studies conducted with nationally representative samples reveal that people support laws designed on the utilitarian principle of deterrence in the abstract, yet reject the consequences of the same when they are applied. Study 1 (N = 133) found that participants assigned punishment to criminals in a manner consistent with a retributive theory of justice rather than deterrence. The verbal justifications for punishment given by these same respondents, however, failed to correlate with their actual retributive behavior. Study 2 (N = 125) again found that people have favorable attitudes towards utilitarian laws and rate them as ‘‘fair’’ in the abstract, but frequently reject them when they are instantiated in ways that support utilitarian theories. These studies reveal people’s inability to know their own motivations, and show that one consequence of this ignorance is to generate support for laws that they ultimately find unjust. Keywords Punishment motives ! Retributive justice ! Deterrence ! Justice ! Self-knowledge Introduction The University of Virginia has one of the oldest, strictest, and perhaps most controversial honor codes in the country: any instance of lying, cheating, or stealing results in immediate and permanent expulsion from the University. This is a classic example of a zero-tolerance policy designed to deter people from behaving badly. K. M. Carlsmith (&) Department of Psychology, Colgate University, Hamilton, NY 13346, USA e-mail: kcarlsmith@colgate.edu 123 Soc Just Res Such a policy violates people’s intuitive sense of justice because it assigns extreme punishments for minor offenses. As a result, every several years there is a groundswell referendum to allow the honor code to assign more proportional sentences. Oddly, however, despite the initial popularity of these referenda, they inevitably fail and the draconian rules are retained. How does one explain this oscillating support for the honor code? One possibility is that when students focus on the policy in the abstract, they find the idea of deterrence (and the zero-tolerance policy that follows) appealing. By contrast, when they observe the policy in action, particularly those cases in which the sentence is disproportionate to the offense, the policy offends their sense of justice and leads them to support the referendum to change the policy. This example speaks to the basic question of why we punish those who break the law. Immanuel Kant (1790/1952) justifies punishment on the basis that perpetrators deserve punishment for the moral wrong committed. He argues that the future consequences of the punishment are irrelevant, and that to adjust the punishment on the expectation that it will increase or decrease future offenses is quite immoral. For Kant, it is the moral status of the offender and his ‘‘internal wickedness’’ (p. 447) that ought to determine punishment: the worse the offense, therefore, the worse the punishment should be. By contrast, utilitarians such as Jeremy Bentham (1843/ 1962) and John Stuart Mill (1871/1998) contend that the purpose of punishment is to deter others from committing crimes, and that punishment in the absence of future benefit is itself immoral. These two positions, and numerous other formulations that attempt to modify or blend them, have occupied moral philosophers for centuries. That criminals ought to be punished is rarely doubted, but why, exactly, and under what circumstances remains as an open question. These two positions are frequently described as the basis for the U.S. legal system (Robinson & Darley, 1997), but their co-existence is at best uneasy (Schroeder, Steel, Woodell, & Bembenek, 2003). Although they converge frequently enough on consensual sentences, they do so by quite different paths. Indeed, most philosophers deem them to be antithetical to each other (cf. Ezorsky, 1972). Thus, to say that one punishes on the basis of both retribution and utility is an incomplete compromise, because there are inevitable situations in which one theory calls for sanction yet the other calls for exculpation. It has thus become an interesting, important, and empirical question to understand the foundation of people’s justifications for punishment. Recent empirical studies have demonstrated that people generally behave in line with Kant’s retributive theory of punishment (Carlsmith, 2006; Carlsmith, Darley, & Robinson, 2002; Glaeser & Sacerdote, 2000; Hamilton & Rytina, 1980; Kahneman, Schkade, & Sunstein, 1998; McFatter 1982; Roberts & Gebotys, 1989; Sunstein, 2003). These studies rely on a variety of methodologies, but converge on the finding that when people punish harmdoers, they are generally responding to factors relevant to a retributive theory of punishment and ignoring factors relevant to utilitarian theories. Thus, for example, in research by Carlsmith et al. (2002), participants adjusted their sentences in response to changes in the moral status of the offender, the magnitude of the harm, and the reasons the perpetrator committed the harm in the first place. They generally ignored information about whether the 123 Soc Just Res perpetrator had committed similar crimes before and whether he was likely to commit them again in the future. These findings, however, contradict numerous polls indicating that people strongly support the deterrence arguments for punishing criminals (Ellsworth & Ross, 1983), and are further belied by the recent profusion of utilitarian laws such as zero-tolerance policies and so-called ‘‘three-strikes’’ laws. Indeed, the philosopher James Rachels (1986, p. 119) declared, ‘‘the victory of the utilitarian ideology has been virtually complete.’’ But if people are truly retributivists at heart, then why do they report such affection for utilitarian principles and laws? One possibility is that people are unaware of their own motivations when they punish. That is, they are aware of the desire, but not of the factors that mobilized the desire. This idea derives from the seminal work by Nisbett and Wilson (1977) on people’s inability to report the causes of their own behavior. I suggest that people behave like retributivists when asked to assign or evaluate sentences, but when asked to verbally justify punishment, they generate reasons on the fly. Those reasons occasionally match the true underlying motivations, but frequently the verbal response draws upon other justifications that were irrelevant to the actual behavior. This is not to say that people punish for random reasons, but rather that they are unable to articulate their true motivations (Wilson, Hodges, & LeFleur, 1995). The punishment may originate in affective sentiments but, due to the difficulty of expressing this motivation, people instead rely on more easily expressed utilitarian justifications. Research by Ellsworth and Ross (1983) provides support for this idea. They found that people frequently cited utilitarian justifications for their support of the death penalty. However, when confronted with evidence that various utilitarian justifications were untenable (e.g., capital punishment actually raises homicide rates), people’s attitudes remained unchanged. This suggests that the attitude was based on some other factor, and that their verbal response stemmed from justifications that were either more accessible to the individual, or perceived to lead to more favorable impressions. Regardless of the mechanism, these results suggest a discrepancy between the real and expressed justifications for punishment. More recent research on this topic has generally ignored self-reports of motivation and instead relied on punishment recommendations to infer the underlying motivation. This ‘‘policy capturing’’ approach (Cooksey, 1996) is particularly useful at identifying policies that will be met with public approval. Such research generally treats the self-reports as unreliable, and typically finds that they are unrelated to actual punishment behavior. For example, in Carlsmith et al. (2002) described above, participants read cases of criminal activity and assigned punishment that seemed appropriate. These punishments were highly sensitive to retributive factors yet insensitive to deterrence factors, and on this basis the authors concluded that people’s intuitions of justice were retributive in nature. However, the verbal responses that the participants gave about their motives for punishment were unrelated to their behavior. That is, people who said they cared about deterrence were no more or less sensitive to the deterrence factors than those who endorsed the retributive theory of justice. The researchers, however, were unable to draw strong conclusions from these data about the internal consistency of words and actions 123 Soc Just Res because it was a between-subjects design. Thus, although mean differences at the group level suggested inconsistency, it was not possible to test whether individuals were themselves inconsistent. The purpose of the present article is to examine how people justify punishment, and to explore the consequences of a discrepancy between what people say about punishment and what people do about punishment. The first study verifies this apparent contradiction by demonstrating that (a) people state that they are motivated by both retribution and deterrence concerns, but (b) behave in accordance with retribution rather than deterrence theory, and that (c) the justification for punishment that people verbally express bears little relationship to their actual behavior. Study 2 extends this finding by demonstrating that people’s ignorance of their motive for punishing provides at least a partial explanation for why they endorse policies that they subsequently declare unfair. Study 1 Study 1 replicates previous research demonstrating that people behave in accordance with a retributive theory of punishment. It employs a within-subjects design so that one can quantify the extent to which each individual is responsive to retributive and utilitarian concerns, and then correlate this result with the factors that participants say were most important to their sentencing. This correlation provides an index of the extent to which people accurately recount the factors that determined their punishment assignations. The key hypothesis is that people will express support for both deterrence and retribution, but that their behavior will reflect almost exclusively retributive motivations. Method Participants Data were collected via an online experimental survey with a broadly representative sample of adults (N = 133). The sample came from a standing panel of participants coordinated by Study Response at Syracuse University, who were offered a chance to win various cash lotteries. Subsets of this panel (N = 95,574) have been used in a variety of peer-reviewed publications, and the panel overall is highly representative of Western countries’ demographics (Stanton & Weiss, 2002). This particular sub-panel of respondents was 54% female with a median age of 41 years. Thirty-six percent were employed full-time, 13% were employed part-time, 23% were retired or unemployed by choice, and 6% were unemployed and searching for work. Thirty percent had only a high-school diploma, 43% had some college experience, 20% completed a baccalaureate degree, 6% had post-baccalaureate experience, and less than 5% were full time students. Eighty-four percent of the sample was Caucasian, and 60% were US residents. Non-US respondents consisted primarily of residents of English-speaking countries, including Canada (33%), Australia (28%), and the UK (13%). 123 Soc Just Res Procedure Participants completed an anonymous online experimental survey. The first page provided a brief overview of the study, and subsequent pages provided the case descriptions and follow-up questions. Materials I constructed four criminal scenarios including the following: driving the wrong way down a one-way street, assaulting a stranger at a crowded movie theater, starting a wildfire, and stealing a stop sign from a blind intersection. Four versions of each scenario were then created by crossing factors related to retribution and deterrence. Half were designed to induce high punishment from a retributive perspective, and the other half to induce low punishment. Similarly, half were designed to elicit high punishment from a deterrence perspective, and half to elicit low punishment. These manipulations are conceptual extensions of manipulations used in prior research (Carlsmith, 2006; Carlsmith et al., 2002; Darley, Carlsmith, & Robinson, 2000; McFatter, 1982), and have been shown to be largely orthogonal to each other. As an example, a high-deterrence case might reveal that the defendant has a very public profile and that the sentence would attract wide attention. For a deterrist, this is precisely the type of case that should receive severe punishment because it could deter many other potential offenders; for a retributionist, this information should be irrelevant to the assigned punishment. A high-retribution case would be one in which the moral severity of the offense was high. Thus, a perpetrator who mocks and humiliates his victim would be more deserving of punishment than one who treats the victim with a modicum of respect. Main effects in this type of design reveal whether people are sensitive to variation in deterrence or retribution factors, and thus whether the factor is a component in their motives to punish. The particular instantiations for the retribution and deterrence manipulations were carefully constructed to represent the factors typically deemed relevant to these two perspectives (see Carlsmith, 2006 for a more complete discussion of these issues). The retributive factors included: the severity of the harm,1 the moral 1 Readers may wonder whether severity of harm is truly orthogonal to utilitarian justifications of punishment. Intuitively, it may seem that society has more need to deter serious crimes than petty crimes, and thus that utilitarians ought to carefully consider the danger posed by a particular crime. There are two responses to this. First, the effect of a given crime extends far beyond the initial victim, and includes all those who subsequently live in fear of future crime and those who become more likely to commit crimes as a result of witnessing an unpunished crime. Thus, the ‘‘cost’’ of punishment (borne by the offender) is almost certainly outweighed by the benefit to society, regardless of the punishment’s severity. Second, the logic of deterrence is that it will prevent future crimes merely by the threat of severe sanction. Thus, when Draco decreed in the 7th century BC that virtually all crimes would be punished by death, he perhaps imagined that no more crimes would be committed, and thus that the sentence would never be enforced. Indeed, if one believes in the efficacy of deterrence, then one need not be concerned about ‘‘overpunishing’’ minor crimes, since the threat of punishment alone will ensure that the punishment is never, in fact, carried out. 123 Soc Just Res offensiveness of the behavior, the intent behind the action, the blameworthiness of the offender, and whether or not the offender was acting in a responsible manner. Each vignette included two of these retribution manipulations. The deterrence manipulations included: the publicity of the crime and subsequent punishment, the frequency of the crime, the likelihood of similar crimes in the future, the likelihood of detecting the crime, and the likelihood of catching the perpetrator. Each vignette included two of these deterrence manipulations. The vignettes and manipulations were pretested with a sample of adult participants (N = 150), and revised to ensure that they were perceived as expected. Each participant read and evaluated one version of each scenario. Across the four scenarios, each participant experienced the four experimental conditions that resulted from the 2 (retribution: high vs. low) 9 2 (deterrence: high vs. low) withinsubjects design. The order of scenario presentation, and the pairing of a given scenario with a particular version of the scenario, was fully counterbalanced across participants in a Greco-Latin square. After each scenario, participants completed a 4-item manipulation check to verify their perception of the deterrence and retribution manipulations, and the culpability of the perpetrator. The primary dependent variable was a standard 13-point sentencing scale that has been used previously (Darley, Carlsmith, & Robinson, 2001), ranging from no punishment to life in prison. Participants were next given a short explanation of retributive2 and deterrence theories and asked to choose the one that best described their reasons for punishing. They were also asked to estimate the importance of each theory on their sentencing (across all of the scenarios) on a 7-point scale ranging from not at all to extremely important. Additionally, participants were asked to indicate the relative influence each theory had on their sentencing using a bipolar scale anchored with deterrence and retribution. The 11-point scale ranged from ‘‘100% deterrence/0% deservingness,’’ to ‘‘50% deterrence/50% deservingness,’’ to ‘‘0% deterrence/100% deservingness.’’ Participants also completed two scales designed to assess individual differences in sentencing orientation. First, they completed the Sentencing Goals Inventory (SGI: Clements, Wasieleski, Chaplin, Kruh, & Brown, 1998), a 30-item, 3-subscale instrument designed to assess the endorsement of classical goals in punishment. The 10 items relating to rehabilitation were omitted, and the subscales for retribution and deterrence were retained. Second, they completed a different sentencing goals scale (McKee & Feather, 2006), a 20-item instrument that assesses endorsement of retribution, deterrence, incapacitation, and rehabilitation, that has been used in other published work (e.g., Feather & Souter, 2002). The 5 items relating to rehabilitation were omitted, and the subscales for retribution, incapacitation, and deterrence were retained. 2 Retributive justice is largely synonymous with Immanuel Kant’s notion of ‘‘just deserts’’ in that they both seek to punish offenders according to their level of deservingness and in proportion to their offense (see Carlsmith et al., 2002, pp. 296–297). However, due to the negative connotations associated with the term ‘‘retribution,’’ I used the more positively valenced term ‘‘deservingness’’ in the survey descriptions and questions. For presentational clarity and to be consistent with the extant literature, I retain the term ‘‘retribution’’ throughout this article. 123 Soc Just Res Results Manipulation Checks Participants perceived the manipulations as intended. The first check for retribution, which referred to the harm committed, was 3.15 in the low retribution condition and 6.57 in the high retribution condition, F(1, 129) = 478.31, p \ .001, g2 = .79. The second check, which referred to either the moral offense, intent, blameworthiness, or responsibility (according to vignette) was 4.20 in the low retribution condition and 5.28 in the high retribution condition, F(1, 126) = 58.75, p \ .001, g2 = .32. The first check for deterrence, which referred to either the frequency of the offense or the publicity of the offense, was 3.00 in the low deterrence condition and 5.74 in the high deterrence condition, F(1, 129) = 191.78, p \ .001, g2 = .60. The second check, which referred to either the difficulty in detecting or solving the crime or the future risk of this type of crime was 3.36 in the low deterrence condition and 4.09 in the high deterrence condition, F(1, 126) = 32.19, p \ .001, g2 = .20. The retribution manipulation had no effect on the deterrence questions, and the deterrence manipulation had only negligible effects on the retribution questions. The perceived harm increased slightly in the high deterrence conditions (4.74 vs. 4.99), but the effect was quite small (g2 = .05). There were no other significant cross-effects or interactions. Assigned Punishment The data replicated the punishment motivation results of previous studies (e.g., Carlsmith, 2006; Carlsmith et al., 2002). A two-way within-subjects Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) on recommended punishment severity revealed high sensitivity to the retribution manipulation such that participants increased the punishment as the moral severity of the crime increased (M = 2.16, SD = 1.46 vs. M = 6.13, SD = 2.93, F(1, 129) = 353.28, p \ .001, g2 = .73). However, they paid little attention to the deterrence manipulation, and only slightly increased punishment across the deterrence conditions (M = 4.04, SD = 2.12 vs. M = 4.25, SD = 2.27, F(1, 29) = 1.68, p = .20, g2 = .01). There was no interaction (F \ 1.0). These results are consistent with previous studies, and show that people are highly sensitive to manipulations of retributive factors, yet insensitive to deterrence factors. Stated Motives I measured stated motives for punishment in a variety of ways (see Table 1). The simplest and most direct method was to ask people to choose between deterrence and retribution as the basis for their decisions in a forced choice paradigm. Sixty percent of the participants chose retribution, 40% chose deterrence. Second, I asked people to state the importance of deterrence and retribution on their punishment decisions using separate 7-point scales. The participants endorsed both retribution (M = 5.52, SD = 1.38) and deterrence (M = 4.92, SD = 1.72) on the unipolar 123 Soc Just Res Table 1 Study 1: Scale means and their correlation with behavior Variable M SD N Correlation with behavior 1. Retributive reasons 5.52 1.38 130 +.07 2. Deterrence reasons 4.92 1.72 130 -.04 3. Other reasons 4.32 1.78 130 -.04 4. 11-point Bipolar scale (deterrence to retribution) 7.32 2.38 130 +.07 5. Forced-choice (deterrence = 1, retribution = 2) 1.59 .50 104 +.06 6. McKee: retribution 5.44 1.23 130 +.01 7. McKee: incapacitation 5.02 1.24 130 -.06 8. McKee: deterrence 5.49 1.24 130 +.01 9. SGI: retribution 5.89 .90 129 +.06 10. SGI: utilitarian 4.56 1.25 129 -.08 Note: All ps [ .35. Scales based on 7-point ratings unless otherwise noted. The 3 scales labeled ‘‘McKee’’ refer to individual subscales of a sentencing goals instrument by McKee and Feather (2006). The 2 ‘‘SGI’’ subscales come from the Sentencing Goals Inventory by Clements et al. (1998) scales (both means are above the ‘‘moderately important’’ label), but expressed a clear preference for retribution compared to deterrence, t(129) = 3.26, p \ .001. Third, on the continuous bipolar scale that forced a trade-off between deterrence and retribution, people again preferred retribution over deterrence by indicating that 63% of their judgment was determined by retribution. On the 11-point scale, the mean response was 7.32, which was significantly above the midpoint labeled ‘‘50% deservingness/50% deterrence,’’ t(129) = 6.35, p \ .001. Fourth, I used two separate measures of general sentencing orientation: the SGI and the McKee Sentencing Scale. Each of the subscales was reliable, with Cronbach Alpha’s ranging between .80 and .89. Behavioral Measure The within-subjects design permitted the creation of a statistic for individuals revealing their relative sensitivity to the retribution and deterrence manipulations. Conceptually, this statistic was the difference between a ‘‘retribution index’’ (which was the punishment assigned in the two high-retribution conditions minus the two low-retribution conditions) and an analogous ‘‘deterrence index.’’ This statistic had a theoretical range of -24 to + 24, with higher scores indicating more sensitivity to the retributive manipulations. The actual range was -7 to + 10 with a SD of 3.26, and a mean of 3.75. Consistency Between Stated and Actual Motives The most straightforward test of consistency between what people say and what people do is to divide the sample according to whether participants described themselves as deterrence punishers or retribution punishers on the initial forced 123 Soc Just Res choice question, and to examine whether their behavioral measure was different. If participants accurately report their motives, then the deterrists ought to have behavioral scores below zero and lower than retributionists. Likewise, the retributionists ought to score above zero and higher than deterrists. The results, however, show that both groups scored significantly above zero (t(42) = 7.27, p \ .001; t(60) = 9.24, p \ .001), and that they were not significantly different from each other. The retributionists’ mean was 3.98 (SD = 3.37) and the deterrists’ mean was 3.65 (SD = 3.29), t(102) = 0.50, p = .62, g2 = .002. A more precise test of the consistency hypothesis is to correlate each of the measures of stated motive with the behavioral measure. Table 1 presents these correlations, and shows clearly the lack of correspondence between the stated and actual motive. None of the correlations is significant, and the strongest correlation— between the SGI utilitarian subscale and behavior—is only -.08. Thus, what people say is not predictive of what people do. Discussion This study asked people to evaluate 4 different scenarios that varied on the dimensions of deterrence and retribution, and to assign the penalties that they deemed fair. Predictably, people were responsive to retribution but not deterrence, replicating previous research (Carlsmith et al., 2002; Carlsmith, 2006; Carlsmith & Darley, 2008). They were further asked to introspect about their reasons for punishing, and to estimate the relative importance of deterrence and retribution in their decision process. The design enabled a statistic for each individual that reflected the relative importance of retribution and deterrence. If people are aware of the motives that guide their decisions to punish, then there ought to have been a strong correlation between the claimed motives and the actual behavior. However, the data reveal no such correlation. Even immediately after assigning punishments, people were unable to report their motivations accurately. I do not claim, and the data do not show, that people do not care about deterrence. Indeed, the data reveal that people support it quite strongly. The data do show, however, that people fail to care about the details of a case that deterrists ought to care about. That is, a person focused on deterring future crime ought to be sensitive to the frequency of the crime, the likelihood of its detection, the publicity of the punishment, and so forth. These participants say they care about deterrence, but they fail to punish in a manner that deterrence theory would call for. This reveals a disconnect between the reasons a person says they punish, and the reasons that they actually punish. A frequent criticism of this type of research is that the manipulations of deterrence and retribution are arbitrary, and thus not truly comparable. Does the small effect for deterrence, for example, reflect the fact that people don’t care about deterrence, or that the factor was so poorly instantiated that the participant’s true motivations were not evoked? This argument can be rebutted in four ways. First, the manipulations were consistent with the tenets of utilitarian theory and with examples validated in previous research (cf. Carlsmith, 2006; Carlsmith et al., 2002; 123 Soc Just Res Darley et al., 2001; McFatter, 1982). Second, there were four different scenarios and multiple instantiations of deterrence to improve the generalizability and to reduce the likelihood that the idiosyncrasies of one scenario would distort the results. Third, the key finding in this research is independent of these effects. In fact, a weak deterrence manipulation would have worked against the hypotheses, since it would inevitably push people to report a greater influence on the retributive factor, and thus lead to a higher concordance between actions and words. Fourth, the manipulation check clearly indicated that people noted the manipulation. Indeed, they reported—wrongly—that it had substantial influence on their punishment. Some might wonder whether people used different punishment theories for each case, and were thus unable to provide a single accurate answer across the four scenarios. It should be noted that these punishment theories are, by their nature, contradictory, and a person who switches among them is probably being driven by some unrelated motive or bias (Carlsmith, Potocki, & West, 2006; Van Prooijen, 2006). Furthermore, no participant suggested this as a problem in their free responses, and data from other studies (Carlsmith et al., 2006) indicate that strong majorities find such ‘‘shifting theories’’ to be inappropriate and unjust. Study 1 contributes to the large collection of studies showing that people have only limited insight into the origins of their own behavior. They have no privileged information and, when asked to explain their actions, generate plausible sounding reasons that are no more accurate than a stranger might provide for them. In other contexts, this general finding has been shown to lead people to pursue courses of action that lead to decreased happiness and well-being (Carlsmith, Wilson, & Gilbert, under review; Wilson, et al., 1995). In the present case, it is possible that a failure to understand one’s own motivation to punish could lead to support of laws and policies that actually violate people’s intuitions of justice. Consider the following case that generated substantial attention nationwide (Zirkel, 1997). In 1996 in Fairborn, Ohio, a 13-year old girl ran afoul of her school’s zero-tolerance policy regarding drug use and distribution. The policy explicitly ignored proportionality between offense and punishment, and instead sought to draw a bright line between permissible and impermissible behavior. Its purpose was not to give the perpetrator what he or she deserves, but rather to deter that person and others from breaking the rule in the first place. The girl in question shared a Midol tablet (obtained from the school nurse) with a friend who was experiencing menstrual cramps, and was subsequently expelled from the school. This example is not unique, and in fact is representative of numerous cases in which utilitarian laws assign sentences wildly disproportionate to offense severity. Indeed, the sentence was subsequently upheld on appeal (Zirkel, 1997). Given that the people, or their representatives, enact these types of deterrencebased laws, how does one reconcile their continued existence with the extensive findings that people’s intuitive theories of punishment are retributive in nature? One possibility is that people who do not know the causes of their own motivation may support utilitarian policies in the abstract, but come to reject such policies when they eventually contradict their intuitive theories of retributive justice. Study 2 explores this possibility. 123 Soc Just Res Study 2 Participants made fairness judgments about two policies in the abstract (retribution and deterrence), or about two possible responses to an actual offense. The first hypothesis predicted that people would generally endorse both abstract policies, but reject the instantiation of the policies when they followed utilitarian principles rather than retributive principles. The second hypothesis predicted that after encountering instantiations of policies that violate retributive justice, participants would reject the utilitarian policies. Method Participants Data were again conducted via an online experiment with a broad sample of adults (N = 125). The demographic composition was approximately equivalent to that of Study 1. Three participants were dropped for failing to complete the survey. Procedure Participants completed an anonymous online experimental survey as before. They read an opening statement describing the problem of drugs in public schools, and that existing policies had failed to solve the incidence of drug use. Half of the participants read two potential policies to address the problem (see Appendix for complete descriptions). The policies described a deterrence-based zero-tolerance policy that was in use during the Midol case described earlier, and a standard retributive policy in which the punishment matched the severity of the offense. This condition permitted a baseline assessment of support for the deterrence and retributive policies. The other participants read one of the two descriptions of a particular drug infraction at school, and were asked to select between two possible responses: a relatively lenient response involving student–parent conferences with the guidance counselor, and the tougher response of permanent expulsion. Some participants read a veridical account of the Midol case, and the remainder read a case in which the student sold a variety of illegal recreational drugs on campus. These participants were then asked to make judgments about the two abstract policies described previously (thus adding a within-subjects component to the design). Materials In all cases participants were initially presented with two options: either two policies, or two responses to an infraction. They were asked to select, in a forcedchoice paradigm, the policy that ‘‘seems more fair to you’’ and the one that they would choose if it were up to them. Next they evaluated each potential response 123 Soc Just Res (e.g., punishment) for fairness and for effectiveness of deterring drug use with 7-point scales anchored by not at all and very. Results Support for Abstract Policies Seventy-percent of participants in the policy-evaluation condition (n = 60) chose the retributive policy over the zero-tolerance policy. This finding was mirrored in the 7-point fairness scale: M = 5.77 (SD = 1.35) vs. 4.02 (SD = 2.30), t(59) = 4.54, p \ .001. Notably, though, both means are at or above the scale midpoint of 4.0, suggesting that respondents were not rejecting either policy. These analyses reveal that people prefer the retributive policy, but that they are also favorably inclined toward the deterrence policy, a finding consistent with the results of Study 1. These data provide a baseline preference for the two policies that will be used in subsequent analyses. Support for Application of Policies This analysis examined the 63 participants who read a specific instantiation of the policies prior to evaluating the policies. They read about a case that was either low or high in offense-severity, and then rated the fairness of two possible outcomes: mild (e.g., a meeting between student, parents, and principal), and severe (e.g., expulsion). This analysis focuses on the fairness ratings made for different punishments (low vs. high, within subject) under differing conditions (mild vs. severe infraction, between subject). Deterrence and retribution theories converge on similar recommendations when the infraction is severe (since the proportional response is equal to the zero-tolerance response), and so I focus particularly on the mild infraction where the two theories make different recommendations. Figure 1 shows that the proportional response was perceived to be fair in the low-severity case (M = 5.52, SD = 1.96), whereas the zero-tolerance response (e.g., expulsion) was markedly unfair in the low-severity case (M = 1.68, SD = 1.05). Expulsion was perceived as a fair response in the high-severity case (M = 5.66, SD = 1.62). The critical cell is the strong response to the low-severity offense. This cell differentiates the utilitarian response from the retributive response in that the punishment is not proportional to the offense. This cell received significantly lower fairness ratings than all other conditions (all p \ .05). Indeed, only 3% of participants chose this option over the more proportional response. The conclusion from this analysis is that people’s perceptions of fairness track a retributive theory of justice, and that they adamantly reject the non-proportional response to infractions that is the hallmark of zero-tolerance policies. 123 Soc Just Res 7 6 5 Potential response Proportional punishment 4 Zero-tolerance 3 2 1 High Low Infraction Severity Fig. 1 Fairness judgments of potential penalties by infraction severity Support for Policies after Application Once people experience these two policies in operation, support for the policies changes dramatically. In the low-severity case, in which a zero-tolerance policy still calls for expulsion but retribution calls for a more measured response, fully 88% of the people who had supported the zero-tolerance policy changed their position and endorsed the proportional response. The baseline approval for zero-tolerance drops from 30% to 6.7%, z = 4.56, p \ .001. Thus, when the two policies are clearly shown to be in conflict, people uniformly choose the retributive policy. This change in support is almost certainly driven by a change in the perceived fairness of the two policies. I conducted a two-way mixed model ANOVA, with offense severity as the between factor and the fairness of the two policies as the repeated measure. The main effects were again qualified by the predicted two-way interaction, F(1, 60) = 83.90, p \ .001, g2 = .19. As can be seen in Fig. 2, the interaction is driven by the differences in the low-severity condition: the two policies are perceived as equally fair after having read about the severe infraction (t(30) = .27, ns), but the zero-tolerance policy is seen as significantly less fair than the retributive policy after having read about the mild infraction (M = 5.71 vs. 2.23, t(30) = 7.27, p \ .001). The retributive policy is perceived to be marginally less fair in the severe infraction condition compared to the mild infraction condition, t(60) = -1.8, p = .07, and the zero-tolerance policy is perceived to be significantly more fair in the high vs. low infraction severity condition, t(61) = 4.90, p \ .001. Mediational Analysis It appears that experiencing a violation of retributive justice leads to a rejection of the offending (e.g., zero-tolerance) policy. More specifically, it appears that this 123 Soc Just Res 7 6 Policy options 5 4 Proportional punishment (retribution) 3 Zero-tolerance (deterrence) 2 1 High Low Infraction Severity Fig. 2 Fairness judgments of policies by infraction severity, after evaluating an actual case .79* Expulsion fairness Infraction severity ______ .90* Preference for expulsion .59* (-.11, ns) Note: N = 122, * p < .001, ns p > .20 Fig. 3 Mediational analysis of infraction severity and preference for expulsion. Note: N = 122, * p \ .001, ns p [ .20 rejection is mediated by the perceived fairness of that policy. This hypothesis was tested through a mediational analysis. Figure 3 shows that the direct effect of infraction severity on policy preference (b = .59) is fully mediated by the perceived fairness of that policy. That is, as the infraction becomes more severe, people are more likely to prefer expulsion as a response. But they do so because they perceive it to be more fair. Phrased differently, people reject expulsion for minor infractions because it violates their sense of fairness. To further test the case for deterrence, I also conducted a test of mediation using the perceived effectiveness of expulsion for deterring drug use. Although perceived effectiveness did predict preference for expulsion (b = .34), it did not mediate the relationship between infraction severity and policy choice (direct b = .59, mediated b = .50, Sobel test of mediation = -.22, p = .83). Finally, I entered the 3 critical variables into a multiple regression to predict policy choice to see whether deterrence effectiveness added anything above and beyond perceived fairness. The results provided a clear answer: perceived fairness was a strong predictor, b = .82, 123 Soc Just Res p \ .001, whereas infraction severity (b = -.08, ns) and perceived effectiveness (b = .11, ns) were not. In summary, Study 2 shows that the moderate support for utilitarian policies in the abstract disappears completely when applied to a low-severity case. People support utilitarian policies when the offense is severe, because the punishment is proportional to the offense. In the low-severity case, people find the utilitarian policies to be unfair and consequently reject them. The perceived utility of the punishment does not drive support for the policies; rather, it is the perceived fairness of the policy. And this fairness tracks a proportional response that is the hallmark of retributive justice. The key finding of this study is that people fail to recognize that the deterrence policy will violate their intuition of justice until after they see it in practice. General Discussion This article presents two studies showing that people have only limited insight into the factors that motivate their desire to punish (Study 1), and that this ignorance can lead people to support policies in the abstract that they reject in actual practice (Study 2). In particular, it shows that people have favorable attitudes towards zerotolerance and other utilitarian policies in general (albeit lower than for retribution), and that they cite deterrence as an important reason for punishment. However, they largely ignore those factors that are critical to deterrence, but are highly sensitive to factors that are critical to retribution when it comes to assigning punishments to perpetrators. For scenarios in which retributive and deterrence theories diverge and logically lead to different punishments, people uniformly choose the retributive outcome and describe it as more fair. Thus, although people say that deterrence is important to them, and although they frequently support laws designed for deterrence, in actual practice they select retributive sentences and reject deterrencebased sentences. Before discussing the implications of these results, it is useful to identify some of the strengths and weaknesses of this study. First, the use of surveys made the entire procedure somewhat hypothetical in nature. I have drawn a sharp distinction between the respondent’s support for policies (‘‘verbal reports’’) and the actual sentences they assigned (‘‘behavior’’), and used the lack of correspondence between the two as the crux of my argument. It is true that what I call behavior is a full step removed from an actual interpersonal encounter, but in defense of this procedure I point out that punishments are often assigned in precisely this sort of impersonal setting. Juries are sequestered and never speak directly with the defendant; managers and professors often mete out punishment from their offices via email or other indirect media. In that sense, it is an ecologically valid approach to the problem. Some will prefer the semantic distinction that these studies measure ‘‘behavioral intentions,’’ and this also seems reasonable. Second, Study 2 relied on a single case, and one should be cautious about extrapolating too far. Although this example provides a clear prototype of 123 Soc Just Res zero-tolerance policies and is taken from a real case, it would be appropriate to verify these findings with more diverse materials. Finally, respondents completed their surveys in uncontrolled environments and may, or may not, have provided careful thinking about the problem. Based on previous experience with similar samples, I am reasonably confident that they provided at least the same minimal levels of attention typical among college samples. Indeed, based on the manipulation checks in Study 1 and the free-response answers to questions at the end of Study 2 (not otherwise reported), the respondents appear to have provided surprisingly thoughtful attention to the survey. Additionally, the sample was more broadly representative than many studies in social psychology. These findings are important for at least two reasons. First, they resolve an ongoing tension within the literature regarding people’s intuitions of justice. The reason that researchers have found support for utilitarian theories is that people frequently articulate utilitarian arguments. Likewise, the reason researchers have found support for retributivist theories is that people’s behavioral responses follow the tenets of retribution theory. The reason that people say one thing yet do another, may reflect the fact that they simply do not know the truth. The question ‘‘Why do I want to punish this person?’’ calls for an attributional analysis, and 30 years of research in social psychology has demonstrated that people are not particularly skilled at this task. Indeed, as Wilson (2002) points out, when it comes to introspection we are all ‘‘strangers to ourselves.’’ Second, these findings can inform policy-makers on the process of creating just laws. Although this recommendation may sound paternalistic, it may be best to obey public opinion cautiously when crafting new laws. For example, California was at the forefront of states that passed 3-strikes laws. These laws, which had overwhelming public support, mandated life sentences for repeat offenders. Surprisingly, though, support for the laws dropped sharply in the decade following its passage, and a recent statewide referendum very nearly repealed them. One explanation for this dramatic shift in opinion stems from the fact that people did not envision a law that would violate the retributive element of proportionality. For example, when Californians encountered the case of Leandro Andrade (Lockyer v. Andrade, 2003), who was sentenced to 50 years for stealing a pair of children’s videos for Christmas presents, they found the outcome to be deeply unjust. Their response was to seek a repeal of that law. It may be that when people encounter utilitarian laws in the abstract, particularly zero-tolerance and 3-strikes laws, they imagine quite severe offenses. That is, the importance of proportionality is so ingrained in their sense of justice that they cannot imagine a rule that ignores this factor. Further, to the extent that people trust the legal system (Tyler & Huo, 2002), they may assume that it will mete out sentences that are proportional to the offense. Thus, in thinking about laws that call for expulsion from school or life in jail, they automatically think of offenses that would deserve such a punishment. When they are confronted with actual cases that do not conform to this erroneous construal—such as Kenneth Payne who was sentenced to 16 years for stealing a Snickers bar—they see the outcome as deeply unjust. 123 Soc Just Res I tested this hypothesis in a brief follow-up study with a new sample of participants from the same general population (N = 209). I asked them to think about two schools that had different drug policies, and gave them abbreviated versions of policies used in Study 2. I hypothesized that people would construe the underlying drug problem differently depending on which policy they read about (cf. Kunda & Sherman-Williams, 1993). As predicted, people thought that the school with a zero-tolerance policy had more severe problems than did the one with a proportional policy, t(208) = 2.57, p = .01. Thus, people make inferences about the school, the students, and the severity of the problem on the basis of information that is contained within the proposed law itself. This finding is reminiscent of the Gricean rules of interpersonal communication that describe how people make inferences based on an interlocutor’s question (Grice, 1975). This finding provides some explanation for why people endorse the utilitarian based policies, but it does not fully tease apart the cognitive and motivational components. On the one hand, it could be purely a cognitive phenomenon in which people fail to accurately process the information presented and reach incorrect conclusions. On the other hand, it could be that people are motivated to justify the status quo as reasonable and just, and thus to perceive the characteristics of the school and the student body as deserving of the more severe policy. The phenomenon identified here may be a case in which people support a policy in general, but fail to perceive that specific instantiations of the policy will lead to unfair outcomes. That is, any general policy will have loopholes and exceptions, and most people are unable to anticipate those in advance. But deterrence-based policies like the ones used in these experiments systematically violate people’s intuitions of justice. For example, Bentham (1843/1962) and numerous other moral philosophers justify why it is morally acceptable, indeed morally imperative, to punish disproportionately or even to punish the innocent. The justification in all cases is the same – the outcome will lead to greater happiness for the greater number, and unhappiness for only the one punished. This phenomenon, then, results from a discrepancy between what people want (both deterrence and retribution), and the actions that people perceive as just (retributive justice). When a person is asked for a justification of punishment, they respond with some combination of motives that almost always include retribution and deterrence. Behaviorally, however, they consistently operate according to principles of retributive justice. These results are broadly supportive of Haidt’s (2001) social intuitionist model of moral judgment. He suggests that moral judgments (such as punishment decisions) are automatic processes that rely on culturally influenced intuitions rather than more formal, thoughtful, and rational processes. Haidt argues that verbal justifications for moral judgments do not reflect the internal process that led to a given decision, but rather to post-hoc processes that follow from the decision. One can conclude from these data that there is a marked discrepancy between the actual and stated motives of punishment. The discrepancy is not random, but rather is skewed such that people are relatively positively inclined towards utilitarian theories when presented with abstract policies, or when the result of a particular policy accords with retributive justice. However, that support erodes sharply when 123 Soc Just Res the outcome deviates from the punishment prescribed by retributive justice, and thus bolsters the claim that people’s intuitive theories of justice are retributive in nature. Finally, I suggest that this discrepancy can lead people to support policies that, when enacted, may lead to outcomes that are perceived to be unfair and unjust by the very people who created them. Acknowledgement I express appreciation to Jennifer Simester who collected data for a pilot version of Study 1, and who provided helpful comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript. Portions of this research were conducted while the author was on leave at Old Dominion University in Norfolk, VA. Appendix Policy A. Any violation of the policy leads to immediate expulsion with no exceptions. The policy is uniform across all grades and schools. The only question to be answered is whether the student violated the policy: if the answer is ‘‘yes’’ then the student is expelled. This policy is designed to eliminate excuses and second-chances, and to send a clear message that the possession, use, and distribution of drugs will not be tolerated in the public schools. The particular type and quantity of drug is irrelevant to this policy. Policy B. Any violation of the policy will be met with a response proportional to the severity of the offense. The most serious offenses—such as the distribution of recreational drugs or the use of ‘‘hard’’ drugs—will lead to immediate expulsion. Lesser offenses—such as the possession of a marijuana pipe—would result in lesser punishments such as suspension. This policy would take into account whether it was a repeated offense, the type and quantity of the drugs, whether they were medicinal or recreational, and whether the person was in possession, using, or distributing the drugs. Consequences would include counseling, loss of privileges, parent conferences, suspension, and expulsion. References Bentham, J. (1962). Principles of penal law. In J. Bowring (Ed.), The works of Jeremy Bentham (p. 396). Edinburgh: W. Tait. (Original work published 1843). Carlsmith, K. M. (2006). The roles of retribution and utility in determining punishment. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 42, 437–451. Carlsmith, K. M., & Darley, J. M. (2008). Psychological aspects of retributive justice. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 40, pp. 193–236). San Diego, CA: Elsevier. Carlsmith, K. M., Darley, J. M., & Robinson, P. H. (2002). Why do we punish? Deterrence and just deserts as motives for punishment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83, 284–299. Carlsmith, K. M., Potocki, A., & West, M. (2006). Shifting theories of punishment as a mechanism of bias expression. Paper presented at the Justice Preconference of the SPSP Annual Meeting. Carlsmith, K. M., Wilson, T. D., & Gilbert, D. (under review). Best served cold: The unexpected consequences of revenge. Colgate University. Clements, C., Wasieleski, D. T., Chaplin, W. F., Kruh, I. P., & Brown, K. P. (1998). The sentencing goals inventory: Development and validation. Poster session presented at the biennial meeting of the American Psychology-Law Society, Redondo Beach, CA. Cooksey, R. W. (1996). Judgment analysis: Theory, methods, and applications. San Diego: Academic Press. 123 Soc Just Res Darley, J. M., Carlsmith, K. M., & Robinson, P. H. (2000). Incapacitation and just deserts as motives for punishment. Law and Human Behavior, 24, 659–683. Darley, J. M., Carlsmith, K. M., & Robinson, P. H. (2001). The ex ante function of the criminal law. Law & Society Review, 35, 701–726. Ellsworth, P. C., & Ross, L. (1983). Public opinion and capital punishment: A close examination of the views of abolitionists and retentionists. Crime and Delinquency, 29, 116–169. Ezorsky, G. (1972). Philosophical perspectives on punishment. Albany: SUNY Press. Feather, N. T., & Souter, J. (2002). Reactions to mandatory sentences in relation to the ethnic identity and criminal history of the offender. Law and Human Behavior, 26, 417–438. Glaeser, E. L., & Sacerdote, B. (2000). The determinants of punishment: Deterrence, incapacitation, and vengeance. NBER working paper no. 7676. Grice, H. P. (1975). Logic and conversation. In D. Davidson & G. Harman (Eds.), The logic of grammar. (pp. 64–75). Encino: Dickenson. Haidt, J. (2001). The emotional dog and its rational tail: A social intuitionist approach to moral judgment. Psychological Review, 108, 814–834. Hamilton, L. V., & Rytina, S. (1980). Social consensus on norms of justice: Should the punishment fit the crime? American Journal of Sociology, 85, 1117–1144. Kahneman, D., Schkade, D., & Sunstein, C. R. (1998). Shared outrage and erratic awards: The psychology of punitive damages. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 16, 49–86. Kant, I. (1952). The science of right. (W. Hastie, Trans.). In R. Hutchins (Ed.), Great books of the western world (pp. 397–446). Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark. (Original work published 1790). Kunda, Z., & Sherman-Williams, B. (1993). Stereotypes and the construal of individuating information. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 19, 90–99. Lockyer V. Andrade, 538 U.S. 63 (2003). McFatter, R. M. (1982). Purposes of punishment: Effects of utilities of criminal sanctions on perceived appropriateness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 67, 255–267. McKee, I., & Feather, N. T. (2006, August). Sentencing goals, human values and punitive personality types: The role of revenge in attitudes towards punishment and rehabilitation. Symposium on ‘‘Legal Justice.’’ 11th biennial meeting of the International Society for Justice Research, Berlin, Germany. Mill, J. S. (1998) Utilitarianism. In R. Crisp (Ed.) J. S. Mill/Utilitarianism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. (Original work published 1871). Nisbett, R. E., & Wilson, T. D. (1977). Telling more than we can know: Verbal reports on mental processes. Psychological Review, 84, 231–259. Rachels J. (1986). The elements of moral philosophy. New York: Random House. Roberts, J. V., & Gebotys, R. J. (1989). The purposes of sentencing: Public support of competing aims. Behavioral Sciences and the Law, 7, 387–402. Robinson, P. H., & Darley, J. M. (1997). The utility of desert. Northwestern University Law Review, 91, 453–499. Schroeder, D. A., Steel, J. E., Woodell, A. J., & Bembenek, A. F. (2003). Justice within social dilemmas. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 7, 374–387. Stanton, J. M., & Weiss, E. M. (2002). Online Panels for Social Science Research: An Introduction to The Study Response Project. (Tech. Rep. No. 13001). Syracuse: Syracuse University, School of Information Studies. Sunstein, C. R. (2003). On the psychology of punishment. Supreme Court Economic Review, 11, 171– 188. Tyler T. R., & Huo, Y. J. (2002). Trust in the law: Encouraging public cooperation with the police and courts. NY: Russell Sage Foundation. Van Prooijen, J.-W. (2006). Retributive reactions to suspected offenders: The importance of social categorizations and guilt probability. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32, 715–726. Wilson, T. D. (2002). Strangers to ourselves: Discovering the adaptive unconscious. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. Wilson, T. D., Hodges, S. D., & LaFleur, S. J. (1995). Effects of introspecting about reasons: Inferring attitudes from accessible thoughts. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 16–28. Zirkel, P. A. (1997). Courtside: The Midol case. Phi Delta Kappan, 78, 803–804. 123