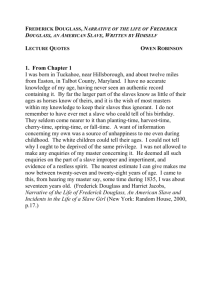

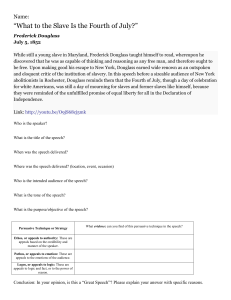

Postcolonial Counter-discourse in The Life and Times of Frederick

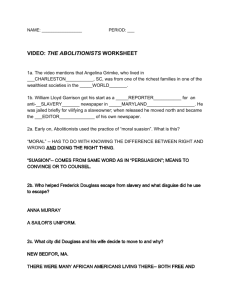

advertisement