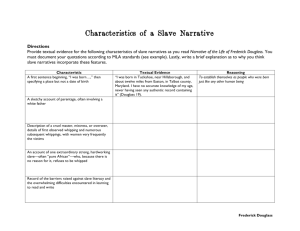

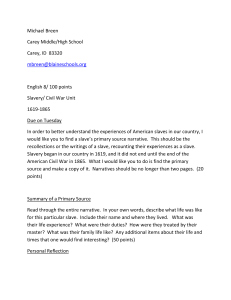

Genre, Authenticity, and Authority in the Antebellum Slave Narrative

advertisement