Born": Slave Narratives, Their Status

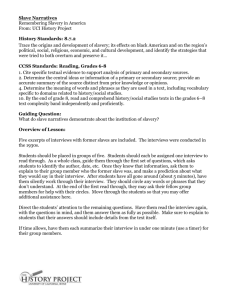

advertisement

"I Was Born": Slave Narratives, Their Status as Autobiography and as Literature Author(s): James Olney Source: Callaloo, No. 20 (Winter, 1984), pp. 46-73 Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2930678 . Accessed: 14/06/2011 03:45 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at . http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=jhup. . Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org. The Johns Hopkins University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Callaloo. http://www.jstor.org 46 "I WAS BORN": SLAVE NARRATIVES, THEIR STATUS AS AUTOBIOGRAPHY AND AS LITERATURE* by JamesOlney Anyonewho setsabout readinga singleslave narrative,or even two or threeslave narratives, thenaturalassumptionthat mightbe forgiven everysuchnarrativewillbe, or oughtto be, a uniqueproduction;forso would go the unconscious argument-are not slave narratives autobiography,and is not everyautobiographythe unique tale, uniquely told, of a unique life?If such a readershould proceed to take up anotherhalfdozen narratives,however(and thereis a greatlot of themfromwhichto choose thehalfdozen), a sensenot of uniqueness samenessis almostcertainto be theresult.And but of overwhelming if our readercontinuesthroughtwo or threedozen more slave narratives,stillhavinghardlybegunto broachthewholebody ofmaterial (one estimateputs the numberof extantnarrativesat over six thouof it sand), he is sureto come away dazed by themererepetitiveness butonly,always all: seldomwillhe discoveranythingnew or different moreand moreofthesame. This raisesa numberofdifficult questions bothforthestudentofautobiography and thestudentofAfro-American literature. be so cumulativeand so invariant, Whyshouldthenarratives so repetitiveand so muchalike? Are the slave narrativesclassifiable under some larger grouping (are they history or literatureor autobiographyor polemicalwriting?and what relationshipdo these largergroupingsbear to one another?);or do thenarrativesrepresent in kind fromany othermode a mutantdevelopmentreallydifferent ofwritingthatmightinitiallyseemto relateto themas parent,as sibling,as cousin,or as someotherformalrelation?Whatnarrativemode, do we findin the slave narratives,and what mannerof story-telling, whatis theplace ofmemorybothin thisparticularvarietyofnarrative and in autobiographymoregenerally?What is therelationshipof the slave narrativesto laternarrativemodesand laterthematiccomplexes of Afro-American writing?The questionsare multipleand manifold. I proposeto come at themand to offersome tentativeanswersby first makingsome observationsabout autobiographyand itsspecialnature as a memorial,creativeact; thenoutliningsomeofthecommonthemes and nearlyinvariableconventionsof slave narratives;and finallyattemptingto determinetheplace of the slave narrative1) in the spec*Thisessaywill appear in The Slave's Narrative,ed. CharlesT. Davis and HenryLouis Gates (New York: OxfordUniv. Press, 1984). 47 trum of autobiographicalwriting,2) in the historyof American and 3) in themakingof an Afro-American literature, literarytradition. I have arguedelsewherethatthereare manydifferent ways thatwe can legitimately understandthe word and the act of autobiography; here,however,I want to restrictmyselfto a fairlyconventionaland common-senseunderstanding of autobiography.I will not attemptto define autobiographybut merely to describe a certain kind of autobiographicalperformance-notthe only kind by any means but the one thatwill allow us to reflectmost clearlyon what goes on in slave narratives.For presentpurposes,then,autobiographymay be understoodas a recollective/narrative act in which the writer,from a certainpoint in his life-the present-, looks back over the events of thatlifeand recountsthemin such a way as to show how thatpast historyhas led to thispresentstate of being. Exercisingmemory,in orderthathe may recollectand narrate,the autobiographeris not a neutraland passive recorderbut rathera creativeand active shaper. Recollection,or memory,in this way a most creativefaculty,goes backwardso thatnarrative,itstwinand counterpart, maygo forward: memoryand narrationmove along thesame lineonlyin reversedirections.Or as in Heraclitus,theway up and theway down, theway back and theway forward,are one and thesame. WhenI say thatmemory is immensely creativeI do notmeanthatitcreatesforitselfeventsthat neveroccurred(of coursethiscan happentoo, but thatis anothermatter). What I mean insteadis thatmemorycreatesthe significanceof eventsin discoveringthepatternintowhichthoseeventsfall.And such a pattern,in thekind of autobiographywherememoryrules,will be a teleologicalone bringingus, in and throughnarration,and as itwere by an inevitableprocess,to theend of all past momentswhichis the present.It is in the interplayof past and present,of presentmemory over past experienceon itsway to becomingpresentbeing, reflecting that events are lifted out of time to be resituatednot in mere chronologicalsequence but in patternedsignificance. Paul Ricoeur,in a paper on "Narrativeand Hermeneutics,"makes thepointin a slightlydifferent way but in a way thatallows us to sort out the place of timeand memoryboth in autobiographyin general slave narrativein particular."Poiesis,"acand in theAfro-American cordingto Ricoeur'sanalysis,"bothreflectsand resolvestheparadox of time";and he continues:"It reflectsit to the extentthatthe act of combinesinvariousproportions two temporaldimensions, emplotment one chronologicaland theothernon-chronological.The firstmay be called the episodic dimension.It characterizesthe storyas made out ofevents.The secondis theconfigurational dimension,thanksto which the plot construessignificantwholes out of scatteredevents."' In autobiographyit is memorythat,in the recollectingand retellingof 48 events,effects"emplotment";it is memorythat,shapingthepast acof thepresent,is responsiblefor"theconcordingto theconfiguration that "construessignificant wholesout of scatdimension" figurational teredevents."It is forthisreason thatin a classic of autobiographical forexample,memoryis notonly likeAugustine'sConfessions, literature themodebutbecomestheverysubjectofthewriting.I shouldimagine, struck however,thatanyreaderofslave narrativesis mostimmediately of dominance "the the almost complete episodic dimension,"the by of total lack dimension,"and thevirtual any "configurational nearly absence of any referenceto memoryor any sense thatmemorydoes anythingbut make the past factsand eventsof slaveryimmediately presentto the writerand his reader. (Thus one oftengets,"I can see evennow .... I can stillhear. .. .," etc.) Thereis a verygood reason forthis,butitsbeinga verygood reasondoes notaltertheconsequence thatthe slave narrative,witha veryfewexceptions,tendsto exhibit a highlyconventional,rigidlyfixedformthatbearsmuchthesamerelationshipto autobiographyin a fullsenseas paintingby numbersbears to paintingas a creativeact. I say thereis a good reason forthis,and thereis: The writerof a slave narrativefindshimselfin an irresolvablytightbind as a result of theveryintentionand premiseof his narrative,whichis to give a pictureof "slaveryas it is." Thus it is thewriter'sclaim,it mustbe his he is not fictionalizing, and he is not claim,thathe is not emplotting, of To act performing any poiesis (=shaping, making). givea truepictureof slaveryas it it reallyis, he mustmaintainthathe exercisesa clear-glass,neutralmemorythatis neithercreativenorfaulty-indeed, if it were creativeit would be eo ipso faultyfor"creative"would be understoodby skepticalreadersas a synonymfor"lying."Thus the ex-slavenarratoris debarredfromuse of a memorythatwould make anythingof his narrativebeyond or otherthan the purely,merely episodic,and he is deniedaccess, by theverynatureand intentof his dimensionof narrative. venture,to the configurational Of the kind of memorycentralto the act of autobiographyas I describedit earlier,ErnstCassirerhas written:"Symbolicmemoryis theprocessby whichman notonlyrepeatshispast experiencebut also thisexperience.Imaginationbecomesa necessaryelement reconstructs oftruerecollection." In thatword"imagination," however,liesthejoker foran ex-slavewho would writethe narrativeof his lifein slavery. Whatwe findAugustinedoingin Book X of theConfessions-offering up a disquisitionon memorythatmakes both memoryitselfand the narrativethatit surroundsfullysymbolic-would be inconceivablein a slave narrative.Of courseex-slavesdo exercisememoryin theirnarratives,but theynevertalk about it as Augustinedoes, as Rousseau does, as Wordsworthdoes, as Thoreau does, as HenryJamesdoes, as 49 a hundredotherautobiographers(not to say novelistslikeProust)do. Ex-slavescannot talk about it because of the premisesaccordingto which theywrite,one of those premisesbeing that thereis nothing doubtfulor mysteriousabout memory:on thecontrary,it is assumed to be a clear, unfailingrecordof eventssharp and distinctthatneed intodescriptivelanguageto become the sequenonly be transformed tialnarrativeof a lifein slavery.In thesame way, theex-slavewriting his narrativecannotaffordto put thepresentin conjunctionwiththe past (again withveryrarebut significant exceptionsto be mentioned later)forfearthatin so doinghe will appear, fromthepresent,to be and falsifying thepast. As a result,theslave reshapingand so distorting narrativeis most oftena non-memorialdescriptionfittedto a preformedmold,a moldwithregulardepressionshereand equallyregular scenes,turnsofphrase, prominences there-virtually obligatoryfigures, and authentications-that over fromnarrativeto observances, carry narrativeand give to themas a group the species characterthatwe designateby the phrase "slave narrative." What is thisspecies characterby whichwe may recognizea slave narrative? The mostobviousdistinguishing markis thatitis an extrememixed ly productiontypicallyincludingany or all of the following: an engravedportraitor photographof the subject of the narrative; or postfixed;poetic testimonials, authenticating prefixed epigraphs,snatchesofpoetryin thetext,poems appended;illustrations before,in the middleof, or afterthenarrativeitself;2interruptions of thenarrative properby way of declamatoryaddressesto the readerand passages thatas to stylemightwell come froman adventurestory,a romance, or a novel of sentiment;a bewilderingvarietyof documents-letters to and fromthe narrator,bills of sale, newspaperclippings,notices of slave auctions and of escaped slaves, certificates of marriage,of manumission,of birthand death, wills, extractsfromlegal codesthatappear beforethetext,in the textitself,in footnotes,and in appendices;and sermonsand anti-slavery speechesand essaystackedon at theend to demonstratepost-narrative activitiesof thenarrator.In out the mixed of slave narrativesone imnature pointing extremely has to how mixed and impure classic mediately acknowledge are or be can also. The last three books ofAugustine's autobiographies for in are a different mode from therestof the Confessions, example, volume, and Rousseau's Confessions,which begins as a novelistic romanceand ends in a paranoid shambles,can hardlybe considered modallyconsistentand all of a piece. Or ifmentionis made of thelettersprefatory and appendedto slavenarratives, thenone thinksquickly of the lettersat the divide of Franklin'sAutobiography,whichhave muchthesameextra-textual existenceas lettersat oppositeendsofslave narratives.But all thissaid, we mustrecognizethatthenarrativelet- 50 as theFranklin tersor theappendedsermonshaven'tthesame intention moreimportant, lettersor Augustine'sexegesisofGenesis;and further, elementsin slave narratives all themixed,heterogeneous, heterogeneric come to be so regular,so constant,so indispensableto themode that theyfinallyestablisha setofconventions-a seriesof observancesthat become virtuallyde riguer-for slave narrativesunto themselves. The conventionsfor slave narrativeswere so early and so firmly establishedthatone can imaginea sortof masteroutlinedrawnfrom thegreatnarrativesand guidingthelesserones. Such an outlinewould look somethinglike this: A. An engravedportrait,signedby the narrator. B. A titlepage thatincludestheclaim,as an integralpartof thetifroma statetle,"Written by Himself"(or someclosevariant:"Written mentof FactsMade by Himself";or "Writtenby a Friend,as Related to Him by BrotherJones";etc.) C. A handfulof testimonialsand/or one or more prefacesor introductions writteneitherby a whiteabolitionistfriendofthenarrator (WilliamLloyd Garrison,WendellPhillips)or by a whiteamanuenforthetext(JohnGreenleafWhitsis/editor/author actuallyresponsible Alexis David Louis Wilson, tier, Chamerovzow),in thecourseofwhich is the reader told that the narrativeis a "plain, unvarnished preface that "has set down inmalice,nothingexaggerated, tale"and been naught drawn from the nothing imagination"-indeed,thetale, it is claimed, of the horrors understates slavery. D. A poetic epigraph,by preferencefromWilliam Cowper. E. The actual narrative: 1. a firstsentencebeginning,"I was born ... ," thenspecifying a but not a of date birth; place 2. a sketchyaccount of parentage,, ofteninvolvinga whitefather; 3. descriptionof a cruelmaster,mistress, or overseer,detailsoffirst observedwhippingand numeroussubsequentwhippings,withwomen veryfrequentlythe victims; 4. an account of one extraordinarily strong,hardworkingslaveoften"pureAfrican"-who, because thereis no reason forit, refuses to be whipped; 5. recordof thebarriersraised againstslave literacyand the overencounteredin learningto read and write; whelmingdifficulties 6. descriptionof a "Christian"slaveholder(oftenof one suchdying in terror)and the accompanyingclaim that "Christian"slaveholders are invariablyworse than those professingno religion; 7. descriptionof theamountsand kindsof food and clothinggiven to slaves, the work requiredof them,the patternof a day, a week, a year; 51 8. account of a slave auction, of familiesbeing separated and mothersclingingto theirchildrenas theyare destroyed,of distraught tornfromthem,of slave cofflesbeing drivenSouth; 9. descriptionof patrols,of failedattempt(s)to escape, of pursuit by men and dogs; 10. descriptionof successfulattempt(s)to escape, lyingby during the day, travellingby nightguidedby theNorthStar, receptionin a freestate by Quakers who offera lavish breakfastand much genial thee/thouconversation; one suggestedby a white 11. takingof a new last name (frequently as a freeman,butretenabolitionist)to accordwithnew social identity tion of firstname as a mark of continuityof individualidentity; 12. reflectionson slavery. materialF. An appendixor appendicescomposedof documentary billsof sale, detailsof purchasefromslavery,newspaperitems-, furon slavery,sermons,anti-slavery therreflections speeches,poems,appeals to the readerforfundsand moral supportin thebattleagainst slavery. Aboutthis'MasterPlan forSlave Narratives"(theironyofthephrastwo observations ing being neitherunintentionalnor insignificant) shouldbe made: First,thatit not onlydescribesratherloosely a great butthatitalso describesquitecloselythegreatest manylessernarratives of themall, Narrativeof theLifeofFrederickDouglass, An American whichparadoxicallytranscendstheslave Slave, Writtenby Himself,3 narrativemode while being at the same time its fullest,most exact Second, thatwhat is beingrecountedin thenarratives representative; of slavery,almostnever is nearlyalways therealitiesof theinstitution theintellectual, emotional,moralgrowthofthenarrator(here,as often, Douglass succeedsin beingan exceptionwithoutceasingto be thebest of describingslavery,but example:he goes beyondthesingleintention he also describesit moreexactlyand moreconvincinglythananyone else). The lives of thenarrativesare never,or almostnever,therefor and fortheirown intrinsic, butnearlyalways themselves uniqueinterest in theircapacityas illustrations of what slaveryis reallylike. Thus in one sense thenarrativelives of theex-slaveswere as muchpossessed and used by the abolitionistsas their actual lives had been by slaveholders.This is why JohnBrown's storyis titledSlave Life in and Georgia and only subtitled"A Narrativeof the Life,Sufferings, Escape of JohnBrown,A FugitiveSlave," and it is why CharlesBall's story (which reads like historicalfictionbased on very extensive research)is called Slaveryin theUnitedStates,withthesomewhatextendedsubtitle"A NarrativeoftheLifeand AdventuresofCharlesBall, A Black Man, who livedfortyyearsin Maryland,SouthCarolina and Georgia, as a slave, undervarious masters,and was one year in the 52 navywithCommodoreBarney,duringthelatewar. Containingan account of the mannersand usages of the plantersand slaveholdersof theSouth-a descriptionof theconditionand treatment of theslaves, withobservationsupon thestateofmoralsamongstthecottonplanters, ofa fugitive and theperilsand sufferings slave,who twiceescapedfrom the cottoncountry."The centralfocus of thesetwo, as of nearlyall and an externalreality,rather thenarratives,is slavery,an institution and subthana particularand individuallifeas it is knowninternally This means that unlike in the narratives autobiography general jectively. are all trainedon one and the same objective reality,they have a coherentand definedaudience,theyhave behindthemand guidingthem an organizedgroup of "sponsors,"and they are possessed of very specificmotives,intentions,and uses understoodby narrators,sponsors,and audiencealike: to revealthetruthof slaveryand so to bring about its abolition.How, then,could the narrativesbe anythingbut verymuch like one another? Severalof theconventionsof slave-narrative writingestablishedby of thistriangular relationship narrator,audience,and sponsorsand the that dictates logic developmentof thoseconventionswillbear and will reward closer scrutiny.The conventionsI have in mind are both thematicand formaland theytendto turnup as oftenin theparapherthenarrativesas in thenarrativesthemselves.I have nalia surrounding on theextra-textual remarked lettersso commonlyassociated already withslave narratives and have suggestedthattheyhave a different logic about themfromthe logic thatallows or impelsFranklinto include similarlyalien documentsin his autobiography;thesame is trueof the to be foundas signedengravedportraitsor photographsso frequently in The the slave narratives. and frontispieces signature(which portrait one mightwell find in other nineteenth-century autobiographical documentsbut withdifferent motivation),like theprefatoryand apthe titular "Written tag pendedletters, by Himself,"and thestandard "I was are intended to attestto the real existenceof born," opening a narrator,thesensebeingthatthestatusof thenarrativewill be continuallycalled intodoubt,so itcannoteven begin,untilthenarrator's realexistenceis firmly established.Of coursetheargumentof theslave narrativesis thattheeventsnarratedare factualand truthful and that all to is the but this a narrator, they reallyhappened second-stagearguis thesimple,existentialclaim: ment;priorto theclaimof truthfulness "I exist."Photographs,portraits,signatures,authenticating lettersall make thesame claim: "This man exists."Only thencan thenarrative begin.And how do mostof themactuallybegin?They beginwiththe existentialclaim repeated."I was born" are the firstwords of Moses Roper'sNarrative,and theyarelikewisethefirstwordsofthenarratives of HenryBibb and HarrietJacobs,of HenryBox Brown4and William 53 Wells Brown,of FrederickDouglass5and JohnThompson,of Samuel RinggoldWard and JamesW. C. Pennington,of AustinStewardand JamesRoberts,ofWilliamGreenand WilliamGrimes,ofLevinTilmon and PeterRandolph,of Louis Hughesand Lewis Clarke, of JohnAndrewJacksonand ThomasH. Jones,ofLewisCharltonand Noah Davis, of JamesWilliamsand William Parkerand William and Ellen Craft (wheretheopeningassertionis variedonlyto theextentofsaying,"My wifeand myselfwere born").6 We can see the necessityforthisfirstand most basic assertionon thepartof theex-slavein thecontrarysituationof an autobiographer likeBenjaminFranklin.Whileany readerwas freeto doubtthemotives ofFranklin's memoir,no one could doubthisexistence,and so Franklin beginsnot withany claimsor proofsthathe was bornand now really existsbut withan explanationof why he has chosen to writesuch a documentas the one in hand. Withtheex-slave,however,it was his existenceand his identity,not his reasonsforwriting,thatwerecalled into question: if the formercould be establishedthe latterwould be obviousand thesamefromone narrativeto another.Franklincitesfour motivesforwritinghisbook (to satisfydescendants'curiosity;to offer an exampleto others;to providehimselfthepleasureofrelivingevents in thetelling;to satisfyhis own vanity),and while one can findnarofeach ofthese rativesby ex-slavesthatmighthave in themsomething motives-JamesMars, for example, displays in part the firstof the motives,Douglass in partthesecond,JosiahHenson in partthethird, and SamuelRinggoldWard in partthefourth-thetruthis thatbehind or representative everyslave narrativethatis in any way characteristic thereis the one same persistentand dominantmotivation,which is determinedby the interplayof narrator,sponsors,and audience and whichitselfdetermines thenarrativein theme,content,and form.The themeis the realityof slaveryand the necessityof abolishingit; the contentis a seriesof eventsand descriptionsthatwill make thereader see and feelthe realitiesof slavery;and the formis a chronological, episodic narrativebeginningwith an assertionof existenceand surroundedby various testimonialevidencesfor thatassertion. In thetitleand subtitleofJohnBrown'snarrativecitedearlier-Slave and Escape ofJohn Lifein Georgia:A Narrativeof theLife,Sufferings, Brown,A FugitiveSlave-we see thatthethemepromisesto be treated on two levels, as it were titularand subtitular:the social or institutional and the personalor individual.What typicallyhappens in the actualnarratives,especiallythebestknownand mostreliableofthem, is that the social theme,the realityof slaveryand the necessityof on thepersonallevel to becomesubthemesof abolishingit,trifurcates and freedomwhich,thoughnotobviouslyand at first literacy,identity, lead intoone anotherin such sightcloselyrelatedmatters,nevertheless 54 and virtually a way thattheyend up beingaltogetherinterdependent as thematicstrands.Here,as so often,Douglass' Narindistinguishable rativeis at once thebestexample,theexceptionalcase, and thesupreme achievement.The fulltitleofDouglass' book is itselfclassic: Narrative of the Life of FrederickDouglass, An AmericanSlave, Writtenby Himself.7There is muchmore to the phrase "writtenby himself,"of course,thanthemerelaconic statementof a fact: it is literallya part ofthenarrative,becomingan importantthematicelementin theretelling of the lifewhereinliteracy,identity,and a sense of freedomare and withoutthefirst, all acquiredsimultaneously accordingto Douglass, the lattertwo would neverhave been. The dual factof literacyand identity("written"and "himself")reflectsback on theterribleironyof the phrase in apposition, "An AmericanSlave": How can both of these-"American"and "Slave"-be true?And thisin turncarriesus back to thename, "FrederickDouglass," whichis writtenall around thenarrative:in thetitle,on theengravedportrait, and as thelastwords of the text: Sincerelyand earnestlyhoping that this littlebook may do somethingtowardthrowinglighton theAmericanslave system, and hasteningtheglad day of deliveranceto the millionsof my brethrenin bonds-faithfullyrelyingupon the power of truth, love, and justice,forsuccessin myhumbleefforts-andsolemnly pledgingmyselfanew to thesacredcause,--I subscribemyself, FREDERICK DOUGLASS "I subscribemyself"-I writemyselfdown in letters,I underwrite my identityand myverybeing,as indeedI have done in and all through theforegoing narrativethathas broughtme to thisplace, thismoment, thisstate of being. The abilityto utterhis name, and more significantly to utterit in the mysteriouscharacterson a page whereit will continueto sound in silenceso longas readerscontinueto construethecharacters,is what Douglass' Narrativeis about, forin thatletteredutteranceis assertion of identityand in identityis freedom-freedomfromslavery,freedom fromignorance,freedomfromnon-being,freedomeven fromtime. WhenWendellPhillips,in a standardletterprefatory to Douglass' Narthat in the he avoided has rative,says knowingDouglass' past always "real name and birthplace" because it is "still dangerous, in Massachusetts,forhonestmen to tell theirnames," one understands well enough what he means by "yourreal name" and the dangerof tellingit-"Nobody knows my name," JamesBaldwinsays. And yet in a veryimportantway Phillipsis profoundlywrong,forDouglass had been sayinghis "real name" ever since escapingfromslaveryin 55 theway in whichhe wentabout creatingand assertinghis identityas a freeman: FrederickDouglass. In theNarrativehe says his real name not whenhe revealsthathe "was born" FrederickBaileybut whenhe below hisportrait beforethebeginning and subscribes putshissignature himselfagain afterthe end of thenarrative.Douglass' name-changes and self-namingare highlyrevealingat each stage in his progress: "FrederickAugustusWashingtonBailey" by the name given him by hismother,he was knownas "Frederick Bailey"or simply"Fred"while growingup; he escaped fromslaveryunderthe name "Stanley,"but when he reachedNew York took thename "FrederickJohnson."(He was marriedin New York underthatname-and gives a copy of the in thetext-by theRev. J.W. C. Penningtonwho marriagecertificate had himselfescaped fromslaverysome tenyearsbeforeDouglass and who would producehis own narrativesomefouryearsafterDouglass.) Finally,in New Bedford,he foundtoo manyJohnsonsand so gave to hishost( one ofthetoo many-Nathan Johnson)theprivilegeofnaminghim,"buttoldhimhe mustnottakefromme thenameof 'Frederick.' I musthold on to that,to preservea senseofmyidentity."Thus a new social identitybut a continuityof personalidentity. In narratingthe eventsthatproducedboth change and continuity in his life,Douglass regularlyreflectsback and forth(and herehe is verymuchtheexception)fromthepersonwrittenabout to theperson writing,froma narrativeof past eventsto a presentnarratorgrown out of thoseevents.In one marvellouslyrevealingpassage describing thecold he suffered fromas a child,Douglass says, 'My feethave been so crackedwiththefrost,thatthepen withwhichI am writingmight be laid in thegashes."One mightbe inclinedto forgetthatitis a vastly different personwritingfromthepersonwrittenabout, but it is a very reminderto referto thewritinginand immenselyeffective significant strumentas a way of realizingthe distancebetweenthe literate,articulatewriterand the illiterate,inarticulatesubject of the writing. Douglasscouldhave said thatthecold causedlesionsin hisfeeta quarter of an inchacross, but in choosingthe writinginstrument held at the I with moment-"the which am writing"-by one now pen present known to the world as FrederickDouglass, he dramatizeshow far removedhe is fromtheboy once called Fred(and other,worsenames, of course)withcracksin his feetand withno moreuse fora pen than forany of theothersignsand appendagesof theeducationthathe had been deniedand thathe would finallyacquire only withthe greatest but also withthegreatest,mosttellingsuccess,as we feelin difficulty thequalityof thenarrativenow flowingfromtheliteraland symbolic and freedom, pen he holdsin hishand. Herewe have literacy,identity, theomnipresent thematictrioof themostimportantslave narratives, all conveyedin a singlestartlingimage.8 56 Thereis, however,onlyone Frederick Douglass amongtheex-slaves who told theirstoriesand the storyof slaveryin a singlenarrative, and in even the best known, most highlyregarded of the other narratives-those,forexample,by WilliamWellsBrown,CharlesBall, HenryBibb, JosiahHenson, Solomon Northup,J.W. C. Pennington, and Moses Roper--all theconventionsare observed-conventionsof content,theme,form,and style-but theyremainjust that: conventionsuntransformed and unredeemed.The firstthreeof theseconventionalaspectsof thenarrativesare, as I have alreadysuggested,pretty betweenthenarratorhimselfand clearlydetermined by therelationship thoseI have termedthesponsors(as well as theaudience) of thenarrative.When the abolitionistsinvitedan ex-slaveto tell his storyof experiencein slaveryto an anti-slaveryconvention,and when they subsequentlysponsoredthe appearance of thatstoryin print,10 they well understoodby themselvesand well had certainclearexpectations, understoodby theex-slavetoo, about thepropercontentto be observed, theproperthemeto be developed,and theproperformto be followed. Moreover,content,theme,and formdiscoveredearly on an appropriatestyleand thatappropriatestylewas also thepersonalstyle displayedby the sponsoringabolitionistsin the lettersand introductionstheyprovidedso generouslyforthenarratives.It is not strange, of course,thatthestyleof an introduction and thestyleof a narrative shouldbe one and thesame in thosecases whereintroduction and narrativewere writtenby the same person-Charles Stears writingintroductionand narrativeof Box Brown,forexample,or David Wilson writingprefaceand narrativeof Solomon Northup.What is strange, is theinstancein whichthe perhaps,and a good deal moreinteresting, of the abolitionist introducer carries over into a narrativethat style is certified as "Writtenby Himself,"and thislatterinstanceis notnearly so isolatedas one mightinitiallysuppose. I want to look somewhat thatI taketo reprecloselyat threevariationson stylisticinterchange sentmoreor less adequatelythespectrumofpossiblerelationships betweenprefatorystyleand narrativestyle,or moregenerallybetween sponsorand narrator:HenryBox Brown,wheretheprefaceand narrativeare bothclearlyin themannerof CharlesStearns;SolomonNorthup,where the enigmaticalprefaceand narrative,althoughnot so both in themanclearlyas in thecase of Box Brown,are nevertheless nerof David Wilson; and HenryBibb,wheretheintroduction is signed by Lucius C. Matlack and theauthor'sprefaceby HenryBibb, and wherethenarrativeis "Writtenby Himself"-but wherealso a single author'spreface,and narrativealike. styleis in controlofintroduction, Box Brown's we are told on the title-page,was Narrative, Henry WRITTEN FROM A STATEMENT OF FACTS MADE BY HIMSELF. WITH REMARKS UPON THE REMEDY FOR SLAVERY. BY CHARLES STEARNS. 57 or not,theorderoftheelementsand thepuncWhetheritis intentional tuationof thissubtitle(withfullstopsafterlinestwo and three)make itveryunclearjustwhatis beingclaimedabout authorshipand stylistic for the narrative.Presumablythe "remarksupon the responsibility for remedy slavery"are by CharlesStearns(who was also, at 25 Cornhill,Boston,thepublisherof theNarrative),but thistitle-pagecould wellleave a readerin doubtabout thepartyresponsibleforthestylistic mannerof thenarration.Such doubtwill soon be dispelled,however, ifthereaderproceedsfromCharlesStearns'"preface"to Box Brown's "narrative"to CharlesStearns'"remarksupon theremedyforslavery." The prefaceis a most poetic, most high-flown,most grandiloquent perorationthat,once crankedup, carriesrightover intoand through thenarrativeto issue in theappendedremarkswhichcome to an end in a REPRESENTATION OF THE BOX in which Box Brown was fromRichmondto Philadelphia.Thus fromthe preface: transported "Not forthepurposeof administering to a prurientdesireto 'hearand see some new thing,'nor to gratifyany inclinationon thepart of the hero of thefollowingstoryto be honoredby man, is thissimpleand touchingnarrativeof theperilsof a seekerafterthe 'boon of liberty,' introducedto the public eye . ... ," etc.-the sentencegoes on three timeslongerthanthisextract,describingas itproceeds"thehorridsufofone as, in a portableprison,shutoutfromthelightofheaven, ferings and nearly deprived of its balmy air, he pursued his fearful journey..... " As is usual in such prefaces,we are addresseddirectly tale,let the by theauthor:"O reader,as you perusethisheart-rending tearofsympathyrollfreelyfromyoureyes,and let thedeep fountains of humanfeeling,whichGod has implantedin thebreastof everyson and daughterof Adam, burstforthfromtheirenclosure,untila stream on to thesurroundingworld, of so invigorating shall flowtherefrom and purifying a nature,as to arousefromthe'deathofthesin'ofslavery, and cleanse fromthe pollutionsthereof,all withwhom you may be connected."We may notbe overwhelmedby thesenseof thissentence but surelywe mustbe by its richrhetoricalmanner. The narrativeitself,whichis all firstpersonand "theplain narrative of our friend,"as the prefacesays, beginsin thismanner: I am not about to harrowthefeelingsof myreadersby a terrificrepresentation of the untoldhorrorsof thatfearfulsystem ofoppression,whichforthirty-three longyearsentwineditssnaky foldsabout my soul, as theserpentof South Americacoils itself around theformof its unfortunate victim.It is not my purpose to descenddeeplyintothedark and noisomecavernsof thehell of slavery,and drag fromtheirfrightful abode thoselost spirits who haunt the souls of the poor slaves, daily and nightlywith theirfrightful presence,and withthefearfulsound of theirter- 58 rificinstruments of torture;for otherpens far abler than mine thatportionof thelabor ofan exposer have effectually performed of the enormitiesof slavery. Sufficeit to say of thispiece of finewritingthatthepen-than which therewereothersfarabler-was heldnotby Box Brownbutby Charles removedthanit is fromthe Stearnsand thatitcould hardlybe further Frederick that that could have been laid in held Douglass, pen by pen thegashes in his feetmade by thecold. At one point in his narrative Box Brownis made to say (afterdescribinghow his brotherwas turned away froma streamwiththeremark"We do not allow niggersto fish"),"Nothingdaunted,however,by thisrebuff,my brotherwent obtainto anotherplace, and was quite successfulin his undertaking, of tribe."" It be Box Brown's a the that finny may ing plentiful supply storywas told from"a statementof factsmade by himself,"but after thosefactshave been dressedup in theexoticrhetoricalgarmentsprovided by Charles Stearnsthereis preciouslittleof Box Brown (other of thebox itself)thatremainsin thenarrative. thantherepresentation And indeed for every fact there are pages of self-conscious,selfgratifying, self-congratulatory philosophizingby Charles Stearns,so thatif thereis any lifehere at all it is the lifeof thatman expressed in his veryown overheatedand foolishprose.12 David Wilsonis a good deal morediscreetthanCharlesStearns,and the relationshipof prefaceto narrativein Twelve Years a Slave is therefore a greatdeal morequestionable,butalso moreinteresting, than in theNarrativeof HenryBox Brown. Wilson'sprefaceis a page and a halflong; Northup'snarrative,witha song at theend and threeor four appendices, is threehundredthirtypages long. In the preface Wilsonsays, "Many of thestatements containedin thefollowingpages are corroboratedby abundant evidence-others rest entirelyupon to thetruth,theeditor, Solomon'sassertion.Thathe has adheredstrictly at least, who has had an opportunityof detectingany contradiction or discrepancyin his statements,is well satisfied.He has invariably repeated the same story without deviating in the slightest particular.... "13 Now Northup'snarrativeis not only a verylong one butis filledwitha vast amountof circumstantial detail,and hence it strainsa reader'scredulitysomewhatto be told thathe "invariably repeatedthesame storywithoutdeviatingin theslightestparticular." Moreover,since the styleof the narrative(as I shall argue in a monotNorthup'sown, we mightwellsuspecta fillment)is demonstrably ingin and fleshingout on thepartof-perhaps not the"onliebegetter" butat least-the actualauthorof thenarrative.Butthisis notthemost interesting aspect of Wilson'sperformancein theprefacenor theone thatwill repay closestexamination.That comes withthe conclusion of the prefacewhich reads as follows: 59 It is believedthatthefollowingaccountof his [Northup's]experienceon Bayou Boeufpresentsa correctpictureof Slavery, in all itslightsand shadows,as it now existsin thatlocality.Unbiased, as he conceives,by any prepossessionsor prejudices,the only object of the editorhas been to give a faithfulhistoryof Solomon Northup'slife,as he receivedit fromhis lips. In theaccomplishment of thatobject,he trustshe has succeeded,notthe numerous faultsof styleand of expressionit may be withstanding foundto contain. To sortout, as faras possible,whatis beingassertedherewe would do well to startwith the final sentence,which is relativelyeasy to understand.To acknowledgefaultsin a publicationand to assume forthemis of coursea commonplacegesturein prefaces, responsibility the thoughwhy questionof styleand expressionshould be so important in giving"a faithfulhistory"of someone's life "as . . . received . . . fromhislips" is notquiteclear; presumablythevirtuesof style and expressionare superaddedto thefaithful historyto giveitwhatever it as thesefall shortthe merits claim and insofar to, literary may lay author feels the need to acknowledgeresponsibilityand apologize. Nevertheless, aside,thereis no doubtabout who puttingthisambiguity is responsibleforwhat in thissentence,which,ifI mightreplaceproof that nouns withnames, would read thus: "In the accomplishment notDavid Wilson trusts has that he [David succeeded, object, Wilson] of which the numerous faults of and withstanding style expression[for it may be foundby the reader David Wilson assumesresponsibility] to contain."The two precedingsentences,however,are altogetherimpenetrableboth in syntaxand in the assertiontheyare presumably designedto make. Castingthe firststatementas a passive one ("It is believed .. .") and danglinga participlein the second ("Unbiased . . . "), so thatwe cannotknow in eithercase to whom the statementshould be attached,Wilson succeeds in obscuringentirelythe It would take too much authoritybeing claimed for the narrative.14 to the the (one might,however,glance space analyze syntax, psychology at the familiaruse of Northup'sgivenname), and the sense of these but I would challengeanyone to diagram the second affirmations, sentence("Unbiased . . . ") with any assuranceat all. As to thenarrativeto whichtheseprefatorysentencesrefer:When we get a sentencelike this one describingNorthup'sgoing into a swamp-"My midnightintrusionhad awakened the featheredtribes [nearrelativesofthe'finnytribe'ofBox Brown/Charles Steams],which seemedto throngthemorassin hundredsof thousands,and theirgarsounds-therewas such rulousthroatspouredforthsuchmultitudinous a fluttering ofwings-such sullenplungesin thewaterall aroundmethat I was affrighted and appalled" (p. 141)-when we get such a 60 sentencewe may thinkit prettyfinewritingand awfullyliterary,but thefinewriteris clearlyDavid WilsonratherthanSolomon Northup. novelist Perhapsa betterinstanceof thewhiteamanuensis/sentimental as received from Norlayinghismanneredstyleoverthefaithful history thup'slips is to be foundin thisdescriptionof a Christmascelebration wherea huge meal was providedby one slaveholderforslaves from surroundingplantations:"They seat themselvesat the rustictablethemaleson one side,thefemaleson theother.The twobetweenwhom theremay have been an exchangeof tenderness, invariablymanageto sitopposite;fortheomnipresent Cupid disdainsnot to hurlhis arrows into the simpleheartsof slaves" (p. 215). The entirepassage should be consultedto get the fulleffectof Wilson's stylisticextravagances when he pulls the stops out, but any readershould be forgivenwho declinesto believethatthislastclause, withitsreference to "thesimple heartsofslaves"and itsself-conscious, invertedsyntax("disdainsnot"), was writtenby someonewho had recentlybeen in slaveryfortwelve years."Red,"we are toldby Wilson'sNorthup,"isdecidedlythefavorite color amongtheenslaveddamselsof myacquaintance.Ifa redribbon does notencircletheneck,you willbe certainto findall thehairoftheir wooly heads tiedup withred stringsof one sortor another"(p. 214). In the light of passages like these, David Wilson's apology for "numerousfaultsof styleand of expression"takes on all sortsof interestingnew meaning.The rustictable, the omnipresentCupid, the simpleheartsof slaves, and thewoollyheads ofenslaveddamsels,like thefinnyand featheredtribes,mightcomefromany sentimental novel of the nineteenthcentury-one, say, by HarrietBeecherStowe; and so it comes as no greatsurpriseto read on the dedicationpage the following:"To HarrietBeecherStowe: Whose Name, Throughoutthe withtheGreatReform:This Narrative,Affording World,Is Identified AnotherKey to UncleTom's Cabin, Is Respectfully Dedicated." While notsurprising, giventhestyleof thenarrative,thisdedicationdoes littleto clarifytheauthoritythatwe are asked to discoverin and behind the narrative,and the dedication,like the pervasivestyle,calls into seriousquestionthestatusof Twelve Years a Slave as autobiography and/or literature.15 ForHenryBibb'snarrativeLuciusC. Matlack suppliedan introduction in a mightypoeticvein in whichhe reflectson theparadox that out of thehorrorsof slaveryhave come some beautifulnarrativeproductions. "Gushingfountainsof poetic thought,have startedfrom beneaththerod ofviolence,thatwilllongcontinueto slakethefeverish thirstofhumanityoutraged,untilswellingto a flooditshallrushwith wastingviolenceover theill-gotten heritageoftheoppressor.Startling incidentsauthenticated,farexcellingfictionin theirtouchingpathos, fromthepen ofself-emancipated slaves,do now exhibitslaveryin such 61 revoltingaspects, as to secure the execrationsof all good men, and becomea monumentmoreenduringthanmarble,in testimony strong as sacredwritagainstit."16The pictureMatlack presentsof an outraged humanitywitha feverishthirstforgushingfountainsstartedup by therodofviolenceis a peculiarone and one thatseems,psychologically speaking, not very healthy. At any rate, the narrativeto which Matlack'sobservationshave immediatereference was, as he says,from the pen of a self-emancipated slave (self-emancipated several times), withmuchtouchingpathos and itdoes indeedcontainstartling incidents about them;but thereallycuriousthingabout Bibb'snarrativeis that it displaysmuchthesame florid,sentimental, declamatoryrhetoricas we findin ghostwritten or as-told-tonarrativesand also in prefaces such as those by Charles Stearns,Louis Alexis Chamerovzow, and LuciusMatlack himself.ConsidertheaccountBibb givesof his courtshipand marriage.Having determined by a hundredsignsthatMalinda loved himeven as he loved her-"I could read itby heralways givof her company;by her pressinginvitationsto ing me thepreference visit even in oppositionto her mother'swill. I could read it in the languageofherbrightand sparklingeye,penciledby theunchangable fingerofnature,thatspake butcould notlie" (pp. 34-35)-Bibb decided to speak and so, as he says, "broachedthe subjectof marriage": I said, "I neverwillgivemyheartnorhand to any girlin marsubriage,untilI firstknowhersentiments upon theall-important of No how I and well love jects Religion Liberty. matter might her,nor how greatthesacrificein carryingout theseGod-given principles.And I here pledge myselffromthiscourse neverto be shakenwhilea singlepulsationof my heartshall continueto throbfor Liberty." And did his "dear girl"funkthe challengethusproposed by Bibb? Far fromit-if anythingshe proved more high-mindedthan Bibb himself. Withthisidea Malinda appeared to be well pleased, and with a smileshe looked me in the face and said, "I have long entertained the same views, and this has been one of the greatest reasonswhyI have notfeltinclinedto enterthemarriedstatewhile a slave; I have always felta desireto be free;I have longcherished a hope thatI shouldyetbe free,eitherby purchaseor running away. In regardto thesubjectof Religion,I have always feltthat itwas a good thing,and somethingthatI would seekforat some futureperiod." It is all to thegood, of course,thatno one has everspokenor could everspeak as Bibb and hisbelovedare said to have done-no one, that novel of date c. 1849.17Though actualis, outsidea bad, sentimental written the narrative,forstyleand tone,mightas wellhave ly by Bibb, 62 been the productof thepen of Lucius Matlack. But the combination of the sentimentalrhetoricof whitefictionand whitepreface-writing witha realisticpresentationof thefactsof slavery,all paradingunder the banner of an authentic-and authenticated-personalnarrative, producessomethingthatis neitherfishnor fowl. A textlike Bibb's is to twoconventionalforms,theslave narrativeand thenovel committed of sentiment, and caughtby both it is unable to transcendeither.Nor thatproducedUncleTom'sCabin is thereasonfarto seek:thesensibility thatsponsoredtheslave was closelyalliedto theabolitionistsensibility narrativesand largelydeterminedthe formthey should take. The master-slaverelationshipmightgo undergroundor it mightbe turned insideout but it was not easily done away with. and tellingdetail in the relationConsiderone small but recurrent ship of whitesponsor to black narrator.JohnBrown'snarrative,we are toldby Louis AlexisChamerovzow,the"Editor"(actuallyauthor) of Slave Life in Georgia, is "a plain, unvarnishedtale of real Slavewritesto Austin life";EdwinScrantom,in hisletter"recommendatory," Stewardofhis Twenty-TwoYearsa Slave and FortyYearsa Freeman, "Let its plain, unvarnishedtale be sentout, and the storyof Slavery and its abominations,again be told by one who has feltin his own heel";thepreface personitsscorpionlash,and theweightofitsgrinding writer("W. M. S.") forExperienceof a Slave in South Carolina calls it "theunvarnished,but ower truetale of JohnAndrewJackson,the thedupe apparently escapedCarolinianslave";JohnGreenleafWhittier, ofhis "ex-slave,"says of The NarrativeofJamesWilliams,"The followingpages containthesimpleand unvarnishedstoryofan AMERICAN SLAVE"; RobertHurnardtellsus thathe was determinedto receive and transmitSolomon Bayley'sNarrative"in his own simple,unvarnished style"; and HarrietTubman too is given the "unvarnished" honorific by Sarah Bradfordin herprefaceto Scenesin theLifeofHarrietTubman: "It is proposedin thislittlebook to give a plain and unvarnishedaccountofsomescenesand adventuresin thelifeofa woman who, thoughone of earth'slowly ones, and of dark-huedskin, has shownan amountofheroismin hercharacterrarelypossessedby those of any stationin life."The factthatthevarnishis laid on verythickly indeed in several of these(Brown,Jackson,and Williams,forexambut it is not theessentialpoint,whichis to ple) is perhapsinteresting, be found in the repeateduse of just this word-"unvarnished"-to describeall thesetales.The OxfordEnglishDictionarywilltellus (which we shouldhave surmisedanyway)thatOthello,anotherfigureof"darkhuedskin"butvastlyheroiccharacter,firstused theword "unvarnished"-"I will a roundunvarnish'dtale deliver/Of mywhole courseof love"; and that,at least so faras theOED recordgoes, theword does notturnup againuntilBurkeuseditin 1780,some175 yearslater("This 63 is a true,unvarnished,undisguisedstateof the affair").I doubt that had an obscure anyonewould imaginethatwhiteeditors/amanuenses passagefromBurkein theback of theircollectivemind-or deep down in thatmind-when theyrepeatedlyused thisword to characterizethe narrativeof theirex-slaves.No, itwas certainlya Shakespeareanhero evoking,and notjustany Shakespeareanhero theywereunconsciously but always Othello, the Noble Moor. Various narratorsof documents"writtenby himself"apologize for theirlack of grace or styleor writingability,and again various narratorssay that theirsare simple,factual,realisticpresentations;but no ex-slavethatI have foundwho writeshis own storycalls it an "unvarnished"tale: the phrase is specificto whiteeditors,amanuenses, and authenticators. writers, Moreover,to turnthematteraround,when an ex-slavemakesan allusionto Shakespeare(whichis naturallya very occurrence)to suggestsomethingabout his situationor iminfrequent ofhischaracter, theallusionis neverto Othello.Frederick plysomething Douglass, forexample,describingall theimaginedhorrorsthatmight overtakehimand his fellowsshouldtheytryto escape, writes,"I say, thispicturesometimesappalled us, and made us: 'ratherbear those ills we had, Than flyto others,thatwe knew not of."' Thus it was in the lightof Hamlet's experienceand characterthat Douglass saw his own, not in the lightof Othello's experienceand character.Not so WilliamLloyd Garrison,however,who says in the prefaceto Douglass' Narrative,"I am confidentthat it is essentially truein all its statements;thatnothinghas been set down in malice, nothingexaggerated,nothingdrawnfromtheimagination.... "18We can be sure that it is entirelyunconscious,this regularallusion to ofwhite Othello,butitsaysmuchabout thepsychologicalrelationship patronto black narratorthattheformershouldinvariablysee thelatter not as Hamlet, not as Lear, not as Antony, or any other Shakespeareanhero but always and only as Othello. When you shall theseunluckydeeds relate, Speak of themas theyare. Nothingextenuate, Nor set down aught in malice. Then mustyou speak Of one thatlov'd not wiselybut too well; Of one not easily jealous, but, being wrought, Perplex'din the extreme.... The Moor, Shakespeare'sor Garrison's,was noble, certainly,but he was also a creatureofunreliablecharacterand irrational passion-such, at least,seemsto have beenthelogicof theabolitionists' attitudetoward 64 theirex-slavespeakersand narrators-and it was just as well forthe whitesponsorto keep him,ifpossible, on a prettyshortleash. Thus it was thattheGarrisonians-thoughnot Garrisonhimself-wereopposed to the idea (and let theiroppositionbe known) thatDouglass and WilliamWellsBrownshouldsecurethemselves againsttheFugitive Slave Law by purchasingtheirfreedomfromex-masters;and because it mightharmtheircause the Garrisoniansattemptedalso to prevent WilliamWells Brownfromdissolvinghis marriage.The reactionfrom the Garrisoniansand fromGarrisonhimselfwhen Douglass insisted on goinghis own way anyhowwas bothexcessiveand revealing,suggestingthatforthemtheMoor had ceased to be noble whilestill,unfortunately, remaininga Moor. My Bondage and My Freedom,Garrisonwrote,"in its second portion,is reekingwith the virus of pertowardsWendellPhillips,myself,and theold organizasonal malignity and basenesstowardsas true tionistsgenerally,and fullof ingratitude and disinterested friendsas any man everyethad upon earth."19That thissimplyis not trueof My Bondage and My Freedomis almostof secondaryinterestto what the words I have italicizedreveal of Garrison'sattitudetoward his ex-slaveand the unconsciouspsychology of betrayed,outragedproprietorship lyingbehindit. And whenGarrisonwrote to his wifethatDouglass' conduct"has been impulsive, inconsiderateand highlyinconsistent"and to Samuel J. May that ofeveryprincipleofhonor,ungrateful Douglass himselfwas "destitute to thelast degreeand malevolentin spirit,"20 thepictureis prettyclear: forGarrison,Douglass had becomeOthellogone wrong,Othellowith all his dark-huedskin,his impulsivenessand passion but none of his nobilityof heroism. The relationship ofsponsorto narratordid notmuchaffectDouglass' own Narrative:he was capable of writinghis storywithoutaskingthe Garrisonians'leave or requiringtheirguidance. But Douglass was an man and an altogether extraordinary exceptionalwriter,and othernarrativesby ex-slaves,even thoseentirely"Writtenby Himself,"scarcely rise above the level of the preformed,imposedand acceptedconventional.Of thenarrativesthatCharlesNicholsjudgesto have been writtenwithoutthehelp of an editor-those by "FrederickDouglass, William Wells Brown, JamesW. C. Pennington,Samuel Ringgold Ward, Austin Steward and perhaps Henry Bibb"21-none but Douglass' has any genuineappeal in itself,apart fromthe testimony itmightprovideabout slavery,or any realclaimto literarymerit.And whenwe go beyond thisbare handfulof narrativesto considerthose writtenunderimmediateabolitionistguidanceand control,we find, as we mightwell expect,even less of individualdistinctionor distinctivenessas thenarratorsshow themselvesmore or less contentto remain slaves to a prescribed,conventional,and imposed form; or 65 perhapsit would be morepreciseto say thattheywere captiveto the abolitionistintentionsand so the question of theirbeing contentor otherwise embracing hardlyenteredin. Justas thetriangular relationship otherthan sponsor,audience,and ex-slavemade ofthelattersomething an entirelyfreecreatorin the tellingof his lifestory,so also it made ofthenarrativeproduced(alwayskeepingtheexceptionalcase in mind) somethingotherthanautobiographyin any fullsense and something of thattermas otherthanliteraturein any reasonableunderstanding an act of creativeimagination.An autobiographyor a piece of imaginativeliteraturemay of course observecertainconventions,but it cannot be only, merelyconventionalwithoutceasing to be satisfacand thatis thecase, I should toryas eitherautobiographyor literature, say, with all the slave narrativesexcept the great one by Frederick Douglass. But herea mostinteresting paradox arises. While we may say that or literature, do notqualifyas eitherautobiography theslave narratives and whilewe mayargue,againstJohnBaylissand GilbertOsofskyand others,thattheyhave no real place in AmericanLiterature(justas we mightargue,and on thesame grounds,againstEllenMoers thatUncle Tom's Cabin is not a greatAmericannovel), yet the undeniablefact is thattheAfro-American literarytraditiontakesitsstart,in themecertainlybut also oftenin contentand form,fromthe slave narratives. RichardWright'sBlack Boy, which many readers(myselfincluded) would take to be his supremeachievementas a creativewriter,providestheperfectcase inpoint,thougha hostof otherscould be adduced thatwouldbe nearlyas exemplary(DuBois' variousautobiographical works; Johnson'sAutobiographyof an Ex-ColouredMan; Baldwin's autobiographicalfictionand essays; Ellison'sInvisibleMan; Gaines' Autobiographyof Miss JanePittman;Maya Angelou'swriting;etc.). In effect,Wrightlooks back to slave narrativesat thesame timethat he projectsdevelopmentsthatwould occurin Afro-American writing afterBlack Boy (publishedin 1945). Thematically,Black Boy reenacts both thegeneral,objectiveportrayalof the realitiesof slaveryas an to whatWrightcalls "The Ethicsof LivingJim institution (transmuted Crow" in thelittlepiece thatlies behindBlack Boy) and also theparthatwe find ticular,individualcomplexof literacy-identity-freedom at the thematiccenterof all of the most importantslave narratives. In contentand formas wellBlackBoy repeats,mutatismutandis,much of thegeneralplan givenearlierin thisessaydescribing thetypicalslave after more or less narrative:Wright,liketheex-slave, a chronological, Crow, includinga episodic account of theconditionsof slavery/Jim or near impossibilityparticularlyvivid descriptionof thedifficulty but also theinescapablenecessity-ofattainingfullliteracy,tellshow he escaped fromsouthernbondage, fleeingtowardwhat he imagined 66 to exercisehis would be freedom,a new identity,and theopportunity hard-wonliteracyin a northern,free-state city.That he did not find exactlywhat he expectedin Chicago and New York changesnothing about Black Boy itself:neitherdid Douglass findeverythinghe anticipatedor desiredin theNorth,but thatpersonallyunhappyfactin no way affectshis Narrative.Wright,impelledby a nascentsense of freedomthatgrew withinhim in directproportionto his increasing in thereadingofrealisticand naturalistic fiction), literacy(particularly fledthe world of the South, and abandoned the identitythatworld had imposedupon him("I was whatthewhiteSouthcalleda 'nigger"'), in searchof anotheridentity,the identityof a writer,preciselythat writerwe know as "RichardWright.""Fromwherein thissouthern darknesshad I caughta sense of freedom?"22 Wrightcould discover only one answer to his question: "It had been only through books . . . thatI had managedto keepmyselfalive in a negatively vital way" (p. 282). It was in his abilityto construelettersand in thebare possibilityof puttinghis lifeintowritingthatWright"caughta sense of freedom"and knewthathe mustworkout a new identity."I could submitand live thelifeof a genialslave," Wrightsays, "but,"he adds, "thatwas impossible"(p. 276). It was impossiblebecause,likeDouglass and otherslaves,he had arrivedat thecrossroadswherethethreepaths ofliteracy,identity, freedommet,and aftersuchknowledgetherewas no turningback. in manywaysbutin otherways BlackBoy resemblesslave narratives itis cruciallydifferent fromitspredecessorsand ancestors.It is ofmore thantrivialinsignificance thatWright'snarrativedoes not beginwith "I was born,"nor is it undertheguidanceof any intentionor impulse otherthanitsown, and whilehis book is largelyepisodicin structure, itis also-precisely by exerciseofsymbolicmemory-"emplotted"and in such a way as to construe"significant wholesout "configurational" of scatteredevents."Ultimately, WrightfreedhimselffromtheSouthat least thisis whathis narrativerecounts-and he was also fortunately free,as theex-slavesgenerallywere not, fromabolitionistcontrol and freeto exercisethatcreativememorythatwas peculiarlyhis. On thepenultimate page ofBlackBoy Wrightsays,"I was leavingtheSouth to flingmyselfintotheunknown,to meetothersituationsthatwould perhapselicitfromme otherresponses.And if I could meetenough of a different life,then,perhaps,graduallyand slowlyI mightlearn who I was, what I mightbe. I was not leavingtheSouth to forgetthe South,butso thatsomeday I mightunderstand it,mightcometo know whatitsrigorshad done to me, to itschildren.I fledso thatthenumbnessof mydefensivelivingmightthawout and let me feelthepainyearslaterand faraway-of whatlivingin theSouthhad meant."Here Wrightnot only exercisesmemorybut also talks about it, reflecting 67 on its creative,therapeutic,redemptive,and liberatingcapacities.In his conclusionWrightharksback to the themesand the formof the slave narratives,and at thesame timehe anticipatesthemeand form in a greatdeal of more recentAfro-American writing,perhapsmost notablyin InvisibleMan. Black Boy is like a nexusjoiningslave narrativesof thepast to themostfullydevelopedliterarycreationsof the theearlier present:throughthepowerofsymbolicmemoryittransforms narrativemode into what everyonemust recognizeas imaginative, creativeliterature, bothautobiographyand fiction.In theirnarratives we mightsay, theex-slavesdid thatwhich,all unknowinglyon their partand onlywhenjoined to capacitiesand possibilitiesnot available to them,led righton to the traditionof Afro-American literatureas we know it now. NOTES 1ProfessorRicoeur has generouslygiven me permissionto quote fromthisunpublishedpaper. 2 I have in mindsuch illustrations as thelargedrawingreproduced to JohnAndrewJackson'sExperienceofa Slave in South as frontispiece Carolina (London: Passmore& Alabaster,1862), describedas a "FacsimileofthegimletwhichI usedto borea hole in thedeckofthevessel"; theengraveddrawingof a torturemachinereproducedon p. 47 of A Narrative of the Adventuresand Escape of Moses Roper, from AmericanSlavery (Philadelphia:Merrihew& Gunn, 1838); and the "REPRESENTATION OF THE BOX, 3 feet1 inchlong, 2 feetwide, 2 feet6 incheshigh,"in whichHenryBox Browntravelledby freight fromRichmondto Philadelphia,reproducedfollowingthetextof the Narrativeof HenryBox Brown,Who Escaped fromSlaveryEnclosed in a Box 3 Feet Long and 2 Wide. Writtenfroma Statementof Facts Made by Himself.WithRemarksupon the Remedyfor Slavery. By Charles Steams. (Boston: Brown & Stearns,1849). The verytitleof Box Brown'sNarrativedemonstrates somethingof themixedmode of slave narratives.On thequestionof thetextof Brown'snarrativesee also notes 4 and 12 below. 3 Douglass' Narrativedivergesfromthemasterplan on E4 (he was himselftheslave who refusedto be whipped),E8 (slave auctionshappenednot to fallwithinhis experience,but he does talkof theseparation of mothersand childrenand the systematicdestructionof slave families),and E10 (he refusesto tellhow he escaped because to do so would close one escape routeto thosestillin slavery;in the Lifeand Times of FrederickDouglass he reveals thathis escape was different fromthe conventionalone). For the purposesof the presentessay- 68 and also, I think,in general-the Narrativeof 1845 is a much more and a betterbook thanDouglass' two laterautobiographical interesting texts:My Bondage and My Freedom(1855) and Life and Times of FrederickDouglass (1881). These lattertwo are diffuseproductions (Bondage and Freedomis threeto fourtimeslongerthan Narrative, Lifeand Timesfiveto sixtimeslonger)thatdissipatethefocalizedenergy of the Narrative in lengthyaccounts of post-slaveryactivitiesabolitionistspeeches,recollectionsof friends,tripsabroad, etc. In interesting ways it seemsto me thattherelativeweaknessof thesetwo laterbooks is analogous to a similarweaknessin theextendedversion of Richard Wright'sautobiographypublishedas AmericanHunger (orginallyconceivedas part of the same textas Black Boy). 4 This is true of the version labelled "first English edition"Narrativeof theLifeof HenryBox Brown,Writtenby Himself(Manchester:Lee & Glynn,1851)-but notoftheearlierAmericaneditionNarrativeof HenryBox Brown,Who Escaped fromSlaveryEnclosed in a Box 3 Feet Long and 2 Wide. Writtenfroma Statementof Facts Made by Himself.WithRemarksupon the Remedyfor Slavery. By CharlesSteams. (Boston: Brown & Stearns,1849). On thebeginning of theAmericaneditionsee the discussionlaterin thisessay, and on the relationshipbetweenthe two textsof Brown'snarrativesee note 12 below. 5 Douglass' Narrative begins this way. Neither Bondage and Freedomnor Lifeand Timesstartswiththeexistentialassertion.This is one thing,thoughby no meanstheonlyor themostimportantone, thatremovesthelattertwobooks fromthecategoryof slave narrative. It is as ifby 1855 and evenmoreby 1881 FrederickDouglass' existence and his identitywere secureenoughand sufficiently well knownthat he no longerfeltthe necessityof the firstand basic assertion. 6 With the exceptionof William Parker's"The Freedman'sStory" (publishedin theFebruaryand March1866 issuesofAtlanticMonthly) all thenarratives listedwereseparatepublications.Therearemanymore brief"narratives"-so briefthat theyhardlywarrantthe title"narrative":froma singleshortparagraphto threeor fourpagesin lengththatbeginwith "I was born"; thereare, forexample,twenty-five or in such the collection of Drew as The Benjamin thirty published Refugee: A North-SideViewofSlavery.I have nottriedto multiplytheinstances by citingminorexamples;thoselistedin thetextincludethemostimportantof the narratives-Roper, Bibb, W. W. Brown, Douglass, Thompson, Ward, Pennington,Steward, Clarke, the Crafts-even is a fraud JamesWilliams,thoughitis generallyagreedthathisnarrative In on Whittier. an Greenleaf unwittingamanuensis,John perpetrated additionto thoselistedin the text,thereare a numberof othernarrativesthatbegin withonly slightvariationson the formulaictag- 69 WilliamHayden:"Thesubjectofthisnarrativewas born";Moses Grandy: "My nameis Moses Grandy;I was born";AndrewJackson:"I, AndrewJackson,was born";ElizabethKeckley:"Mylifehas beenan eventfulone. I was born"; Thomas L. Johnson:"Accordingto information " receivedfrommymother,ifthereckoningis correct,I was born... is more than these the variation Solomon interesting Perhaps playedby Northup,who was born a freeman in New York State and was kidnapped and sentintoslaveryfortwelveyears;thushe commencesnot with"I was born"but with"Havingbeen borna freeman"-as itwere the participialcontingencythat endows his narrativewith a special fromothernarratives. poignancyand a markeddifference Thereis a nice and ironicturnon the"I was born"insistencein the ratherfoolishscene in Uncle Tom's Cabin (ChapterXX) when Topsy famouslyopinesthatshewas notmadebutjust"grow'd."Miss Ophelia catechizesher: " 'Wherewere you born?' 'Neverwas born!' persisted Topsy." Escaped slaves who hadn'tTopsy's peculiarcombinationof Stowe-icresignationand manichighspiritsin theface of an imposed were impelledto assertover and over, "I non-existence non-identity, was born." 7 Douglass' titleis classic to the degreethatit is virtuallyrepeated by HenryBibb, changingonly thename in theformulaand inserting readers:Narrative "Adventures," presumablyto attractspectacle-loving the and An Adventures American Bibb, Slave, Writof Life of Henry tenby Himself.Douglass' Narrativewas publishedin 1845, Bibb's in 1849. I suspectthatBibb derivedhis titledirectlyfromDouglass. That ex-slaveswritingtheirnarrativeswereaware of earlierproductionsby fellowex-slaves(and thuswere impelledto samenessin narrativeby outrightimitationas well as by the conditionsof narrationadduced in thetextabove) is madeclearin theprefaceto TheLifeofJohnThompson, A FugitiveSlave; ContainingHis Historyof25 Yearsin Bondage, and His ProvidentialEscape. Writtenby Himself(Worcester:Published by JohnThompson,1856), p. v: "It was suggestedto me about two yearssince,afterrelatingto manythemain factsrelativeto my bondage and escape to theland of freedom,thatit would be a desirable thingto put thesefactsintopermanentform.I firstsoughtto discover whathad been said by otherpartnersin bondage once, but in freedom now...." Withthisforewarning thereadershould not be surprised to discoverthatThompson'snarrativefollowstheconventionsof the formveryclosely indeed. 8 However much Douglass changed his narrativein successive incarnations-theopeningparagraph,for example, underwentconchose to retainthissentenceintact.It ocsiderabletransformation-he curson p. 52 of theNarrativeof theLifeof FrederickDouglass . . . ed. BenjaminQuarles (Cambridge,Mass., 1960); on p. 132 ofMy Bon- 70 dage and My Freedom,intro.PhilipS. Foner(New York, 1969); and on p. 72 of Lifeand Timesof FrederickDouglass, intro.RayfordW. Logan (New York, 1962). 9 For convenienceI have adopted thislistfromJohnF. Bayliss'introductionto Black Slave Narratives(New York, 1970), p. 18. As will be apparent,however,I do not agreewiththepointBaylisswishesto makewithhis list. Having quoted fromMarion Wilson Starling'sunpublished dissertation,"The Black Slave Narrative: Its Place in AmericanLiteraryHistory,"to theeffectthattheslave narratives,except those from Equiano and Douglass, are not generallyvery as literature, distinguished Baylisscontinues:"Starlingis beingunfair heresincethenarrativesdo show a diversityofinteresting styles... The leadingnarratives, suchas thoseofDouglass,WilliamWellsBrown, and Roperdeserveto be conBall,Bibb,Henson,Northup,Pennington, for a in sidered place Americanliterature,a place beyond themerely historical."Since Ball's narrativewas writtenby one "Mr. Fisher"and Northup'sby David Wilson,and sinceHenson'snarrativeshowsa good one mightexpectfroma man who billedhimself deal of thecharlantry as 'The OriginalUncleTom,"itseemsat besta strategic errorforBayliss to includethemamongthoseslave narrativessaid to show thegreatest literarydistinction.To putit anotherway, itwould be neithersurprisifMr. Fisher(a whiteman),David Wilson ingnorspeciallymeritorious white and Henson (a man), Josiah (The OriginalUncle Tom) were to of "a display diversity interesting styles"whentheirnarrativesare put those W. W. Brown,Bibb, Pennington,and alongside by Douglass, But the fact,as I shallarguein thetext,is that Roper. reallyinteresting do not show a of they diversity interesting styles. 10Here we discoveranotherminorbut revealingdetail of the conventionestablishing itself.Justas itbecameconventionalto have a signed portraitand authenticating so it became at least letters/prefaces, semi-conventional to have an imprintreadingmore or less like this: "Boston:Anti-Slavery Office,25 Cornhill."A Cornhilladdressis given the for,amongothers, narrativesof Douglass, WilliamWells Brown, Box Brown,Thomas Jones,JosiahHenson,Moses Grandy,and James Williams.The lastoftheseis especiallyinteresting for,althoughitseems thathis narrativeis at leastsemi-fraudulent, Williamsis on thispoint, as on so many others,altogetherrepresentative. 11Narrativeof HenryBox Brown.... (Boston: Brown& Stears, 25. 1849), p. 12 The questionof thetextof Brown'sNarrativeis a good deal more complicatedthanI have space to show, but thatcomplicationrather than invalidatesmy argumentabove. The textI analyze strengthens above was publishedin Boston in 1849. In 1851 a "firstEnglishedition"was publishedin Manchesterwiththespecification"Writtenby 71 Himself."It would appear that in preparingthe Americanedition Steamsworkedfroma ms. copy ofwhatwould be publishedtwoyears lateras the firstEnglishedition-or fromsome ur-textlyingbehind both. In any case, Stearnshas laid on theTrue AbolitionistStylevery heavily,but thereis already,in the version"Writtenby Himself,"a good deal of the abolitionistmannerpresentin diction,syntax,and tone.IfthefirstEnglisheditionwas reallywrittenby Brownthiswould makehiscase parallelto thecase ofHenryBibb,discussedbelow,where theabolitioniststyleinsinuatesitselfinto the textand takes over the styleof the writingeven when thatis actuallydone by an ex-slave. This is not theplace forit, but therelationshipbetweenthetwo texts, thevariationsthatoccurin them,and theexplanationforthosevariationswould provide the subjectforan immenselyinteresting study. 13 Twelve Years a Slave: Narrative of Solomon Northup,a Citizen of New-York,Kidnapped in WashingtonCity in 1841, and Rescued in 1853, froma Cotton PlantationNear the Red River,in Louisiana (Auburn: Derby & Miller,1853), p. xv. Referencesin the textare to thisfirstedition. 14 I am surprised thatRobertStepto,in his excellentanalysisof the internalworkingsof theWilson/Northup book, doesn'tmake moreof thisquestionofwhereto locatetherealauthority ofthebook. See From Behindthe Veil: A Study of Afro-American Narrative(Urbana, Ill., 1979), pp. 11-16. Whetherintentionally or not,GilbertOsofskybadlymisleadsreaders of thebook unfortunately called Puttin'On Ole Massa when he fails to includethe"Editor'sPreface"by David Wilsonwithhis printingof TwelveYearsa Slave: NarrativeofSolomonNorthup.Thereis nothing in Osofsky'stextto suggestthatDavid Wilsonor anyoneelse butNorthuphad anythingto do withthe narrative-on the contrary:"Northup,Brown,and Bibb, as theirautobiographiesdemonstrate,were menof creativity, wisdomand talent.Each was capable of writinghis lifestorywithsophistication" (Puttin'On Ole Massa [NewYork,1969], p. 44). Northuppreciselydoes not writehis lifestory,eitherwithor withoutsophistication,and Osofskyis guiltyof badly obscuringthis fact.Osofsky'sliteraryjudgement,withtwo-thirds of whichI do not agree,is that"The autobiographiesofFrederick Douglass, HenryBibb, and SolomonNorthupfuseimaginativestylewithkeennessof insight. and self-critical, They are penetrating superiorautobiographyby any standards"(p. 10). 15 To anticipateone possibleobjection,I would argue thatthecase is essentiallydifferent withThe AutobiographyofMalcolm X, written by Alex Haley. To put it simply,therewere manythingsin common between Haley and Malcolm X; between white amanuenses/editors/authors and ex-slaves, on the other hand, almost nothingwas shared. 72 Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Henry Bibb, An AmericanSlave, Writtenby Himself.Withan Introductionby Lucius C. Matlack (New York: Publishedby the Author; 5 Spruce Street, 1849), p. i. Page citationsin the textare fromthisfirstedition. of slave narratives-the It is a greatpitythatin modernreprintings threein Osofsky'sPuttin'On Ole Massa, forexample-the illustrations in theoriginalsare omitted.A modemreadermissesmuchof theflavor so fullof pathos and of a narrativelike Bibb's when theillustrations, tendersentiment, not to mentionsome exquisitecrueltyand violence, are not withthe text.The two illustrationson p. 45 (captions: "Can a motherforgether sucklingchild?" and "The tendermerciesof the wicked are cruel"),the one on p. 53 ("Never mindthe money"),and theone on p. 81 ("My heartis almostbroken")can be takenas typical. in Bibb's narAn interesting psychologicalfactabout theillustrations rativeis thatof the twenty-onetotal,eighteeninvolve some formof of physicalcruelty,torture,or brutality.The uncaptionedillustration p. 133 of two naked slaves on whom some infernalpunishmentis beingpractisedsaysmuchabout (in Matlack'sphrase)thereader'sfeverish thirstforgushingbeautifulfountains"startedfrombeneaththerod of violence." 17 Or 1852, the date of Uncle Tom's Cabin. HarrietBeecherStowe recognizeda kindrednovelisticspiritwhenshe read one (justas David Wilson/SolomonNorthupdid). In 1851, when she was writingUncle Tom's Cabin, Stowe wroteto FrederickDouglass sayingthatshe was about lifeon a cottonplantationforhernovel: "I seekinginformation have beforeme an able paper writtenby a southernplanterin which thedetails& modus operandiare givenfromhis pointof sight-I am anxiousto have some morefromanotherstandpoint-I wishto be able to make a picturethatshallbe graphic& trueto naturein itsdetailsSuch a person as HenryBibb, if in thiscountry,mightgive me just I desire."This letteris dated July9, 1851 and thekindof information has been transcribedfroma photographiccopy reproducedin Ellen Moers, HarrietBeecher Stowe and American Literature(Hartford, Conn.: Stowe-Day Foundation,1978), p. 14. 18 Since writingthe above, I discover that in his Life and Times Douglass says of theconclusionof his abolitionistwork,"Othello'soccupationwas gone" (New York: Collier-Macmillan,1962, p. 373), but matterfromthewhitesponsor's thisstillseemsto me rathera different oftheblack invariantallusionto Othelloin attesting to thetruthfulness account. narrator's A contemporaryreviewerof The Interesting Narrativeof the Life the or Gustavus Vassa, Africanwrote,in The of Olaudah Equiano, GeneralMagazine and ImpartialReview (July1789), "This is 'a round unvarnishedtale'of thechequeredadventuresof an African .... "(see 16 73 appendixto vol. I of The Lifeof Olaudah Equiano, ed. Paul Edwards [London: Dawsons of Pall Mall, 1969]. JohnGreenleafWhittier,thoughstungonce in his sponsorshipof JamesWilliams'Narrative,did not shrinkfroma second,similarvennote" to theAutobiographyof the ture,writing,in his "introductory Rev. JosiahHenson (Mrs. HarrietBeecherStowe's "Uncle Tom") also knownas UncleTom's StoryofHis LifeFrom1789 to 1879-"The earlylifeof theauthor,as a slave, . . . provesthatin theterriblepicturesof 'Uncle Tom's Cabin' thereis 'nothingextenuateor aughtset down in malice"' (Boston: B. B. Russell & Co., 1879, p. viii). 19 Quoted by Philip S. Foner in the introduction to My Bondage and My Freedom,pp. xi-xii. 20 Both quotationsfromBenjaminQuarles, "The Breach Between Douglass and Garrison,"JournalofNegroHistory,XXIII (April1938), p. 147, note 19, and p. 154. 21 The listis fromNichols' (Brown unpublisheddoctoraldissertation University,1948), "A Study of the Slave Narrative,"p. 9. 22Black Boy: A Record Childhoodand Youth(New York, 1966), of p. 282.