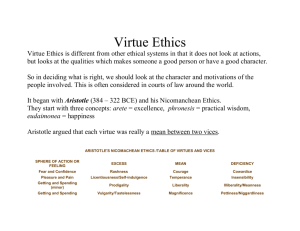

ARISTOTLE NICOMACHEAN ETHICS :Index.

advertisement