Excerpt from Nineties

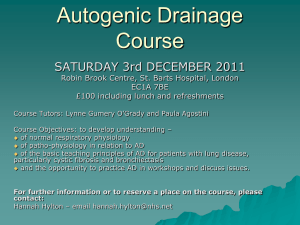

advertisement

lucy ives from NINETIES H annah’s family has a small apartment downtown. I still go there. There are two cats with eyes like cut grapes and Hannah’s parents and Hannah’s older brother and Hannah and a baby girl with dark red hair. People say Hannah’s hair is strawberry blond and reach out to touch it. Hannah calls my house so often some nights my mother asks me not to answer the phone. When I do talk to Hannah she always wants me to look at a mail-order catalogue we have both received and tell her what I think is best on every page. Hannah is refined. She knows what a kid glove is. She talks about Arabian horses. I come over and Hannah shows me a new page in her notebook. A girl in kelly green, high-heeled boots hovers above what appears to be a blue dog leash. “It’s Darla and her eel,” Hannah says. I can’t think for a second. “The eel is an electric eel who died and then came back as a ghost in order to be her talisman.” “Oh.” I nod. Another time we play dolls. I try to show how one doll might fight with another doll. I accidentally use the foot of a plastic doll to kick a porcelain doll’s face in. I stare at the pit in the head. Hannah looks calmly into my lap. She says, “I’m getting my dad.” Hannah’s father is a fat man with a beard. He is an editor at an elite literary review. He grew up in the South, “In the woods,” Hannah says. Hannah’s father owns a white guinea pig. He likes to bring the animal into the living room and place it on his chest like a bib. The guinea pig is named Daniel. Hannah’s dad claims he knows the day and month on which it was born. On the morning of Daniel’s birthday, Hannah’s dad puts a little cone-shaped hat with a chin elastic over Daniel’s snout and gives Daniel a frond of lettuce. When Hannah is bad, her father calls her “roothog.” “What are you roothogs doing?” Hannah’s mother is the editor of a magazine about parenting. She is a big woman, nearly six feet. Hannah maintains her mother is violently al- TK lergic to all varieties of imitation gold or silver. Her office is full of infant toy samples and diapers and formula and boxes of vitamin-enriched crackers. “Come here,” Hannah says when we go to visit her mother. Hannah climbs up the radiator that runs the length of the two windows that form the north and west walls of her mother’s office. Hannah presses her forehead against the glass and gazes down the side of the high-rise to the street thirty stories below, where dots flow. Hannah says that her mother grew up with nine brothers in a mansion in Maine. Hannah says that her mother’s parents are direct descendants of a lord who lived in a castle in England and there is some chance that she, Hannah, may one day be required to live there. Sometimes Hannah’s mother tells us a story about childhood. When Hannah’s mother was a little girl she went for a walk in the forest and found an old doll lying in some leaves. Hannah’s mother named the doll Diarrhea Poop Smell. Hannah and I go to a store that sells minerals. Hannah asks me to buy the same jade ring as her then flushes her ring down the toilet. Hannah says we are like twins. Hannah bites me. She makes a tourniquet with an embroidered belt from L.L. Bean. Hannah’s brother lives in the room next to hers. It smells like glue. There are posters on the walls of women kneeling in the ocean. When he is home, Hannah’s brother wears fingerless gloves and does not speak. He glides behind our backs like a statue on a mechanized track. When Hannah’s mother returns from work, she disappears into her bedroom. An hour later she emerges in compression shorts, her skin blotched from interaction with a NordicTrak. Hannah’s father comes home and goes to the fridge. He carries a glass of milk and Hydrox to the living room. Hannah’s little sister dances in front of the bookshelf. Hannah sits crosslegged and gives me a rose garden on my right arm. A Current Affair comes on. TK