Isidore of Seville

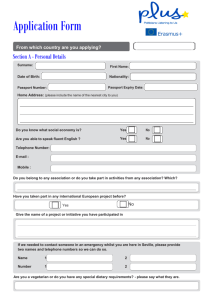

advertisement

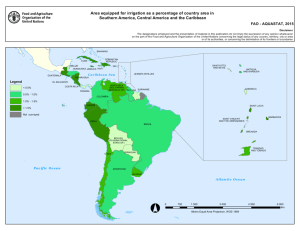

Isidore of Seville 1 Isidore of Seville This article is about the Archbishop of Seville. For the Spanish peasant and patron saint of Madrid, see Isidore the Laborer. Saint Isidore of Seville St. Isidore, depicted by Murillo Bishop, Confessor, and Doctor of the Church Born c. 560 Cartagena, Spain Died 4 April 636 Seville, Spain Honored in Roman Catholic Church Eastern Orthodox Church Canonized 1598, Rome by Pope Clement VIII Feast 4 April Attributes bees; Bishop holding a pen while surrounded by a swarm of bees; bishop standing near a beehive; old bishop with a prince at his feet; pen; priest or bishop with pen and book; with Saint Leander, Saint Fulgentius, and Saint Florentina; with his Etymologiae Patronage the Internet, computer users, computer technicians, programmers, students Saint Isidore of Seville (Latin: Isidorus Hispalensis; c. 560 – 4 April 636) served as Archbishop of Seville for more than three decades and is considered, as the 19th-century historian Montalembert put it in an oft-quoted phrase, "The last scholar of the ancient world".[1] At a time of disintegration of classical culture,[2] and aristocratic violence and illiteracy, he was involved in the conversion of the royal Visigothic Arians to Catholicism, both assisting his brother Leander of Seville, and continuing after his brother's death. He was influential in the inner circle of Sisebut, Visigothic king of Hispania. Like Leander, he played a prominent role in the Councils of Toledo and Seville. The Visigothic legislation that resulted from these councils influenced the beginnings of representative government. His fame after his death was based on his Etymologiae, an etymological encyclopedia which assembled extracts of many books from classical antiquity that would have otherwise been lost. Isidore of Seville 2 Life Childhood and education Isidore was probably born in Cartagena, Spain to Severianus and Theodora. His father belonged to a Hispano-Roman family of high social rank while his mother was of Visigothic origin and apparently, was distantly related to Visigothic royalty.Wikipedia:Citation needed His parents were members of an influential family who were instrumental in the political-religious manoeuvring that converted the Visigothic kings from Arianism to Catholicism. The Catholic Church celebrates him and all his siblings as known saints: • An elder brother, Saint Leander of Seville, immediately preceded Saint Isidore as Archbishop of Seville and, while in office, opposed king Liuvigild. • A younger brother, Saint Fulgentius of Cartagena, served as the Bishop of Astigi at the start of the new reign of the Catholic King Reccared. • His sister, Saint Florentina, served God as a nun and allegedly ruled over forty convents and one thousand consecrated religious. This claim seems unlikely; however, given the few functioning monastic institutions in Iberia during her lifetime, the claim could be creditable.[3] Isidore received his elementary education in the Cathedral school of Seville. In this institution, the first of its kind in Iberia, a body of learned men including Archbishop Saint Leander of Seville taught the trivium and quadrivium, the classic liberal arts. Saint Isidore applied himself to study diligently enough that he quickly mastered at least a pedestrian level of Latin,[4] a smattering of Greek, and some Hebrew. Two centuries of Gothic control of Iberia incrementally suppressed the ancient institutions, classic learning, and manners of the Roman Empire. The associated culture entered a period of long-term decline. The ruling Visigoths nevertheless showed some respect for the outward trappings of Roman culture. Arianism meanwhile took deep root among the Visigoths as the form of Christianity that they received. Scholars may debate whether Isidore ever personally embraced monastic life or affiliated with any religious order, but he undoubtedly esteemed the monks highly. Bishop of Seville After the death of Saint Leander of Seville on 13 March 600 or 601, Isidore succeeded to the See of Seville. On his elevation to the episcopate, he immediately constituted himself as protector of monks. Saint Isidore recognized that the spiritual and material welfare of the people of his See depended on assimilation of remnant Roman and ruling barbarian cultures, and consequently attempted to weld the peoples and subcultures of the Visigothic kingdom into a united nation. He used all available religious resources toward this end and succeeded. Isidore practically eradicated the heresy of Arianism and completely stifled the new heresy of Acephali at its very outset. Archbishop Isidore strengthened religious discipline throughout his See. Archbishop Isidore also used resources of education to counteract increasingly influential Gothic barbarism throughout his episcopal jurisdiction. His quickening spirit animated the educational movement centered on Seville. Saint Isidore introduced Aristotle to his countrymen long before the Arabs studied Greek philosophy extensively. Statue of Isidore of Seville by José Alcoverro, 1892, outside the Biblioteca Nacional de España, in Madrid. In 619, Saint Isidore of Seville pronounced anathema against any ecclesiastic who in any way should molest either the monasteries. Isidore of Seville 3 Second Synod of Seville (November 618 or 619) Through the enlightened statecraft of his two brothers, the Councils of Seville and Toledo emanated Visigothic legislation which influenced the beginnings of representative government.Wikipedia:Citation needed Saint Isidore presided over the Second Council of Seville, begun on 13 November 619, in the reign of King Sisebut. The bishops of Gaul and Narbonne and the Hispanic prelates all attended. The Acts of the Council fully set forth the nature of Christ, countering Arian conceptions. Fourth National Council of Toledo Main article: Fourth Council of Toledo All bishops of Hispania attended the Fourth National Council of Toledo, begun on 5 December 633. The aged Archbishop Saint Isidore presided over its deliberations and originated most enactments of the council. Through Isidore's influence, this Council of Toledo promulgated a decree, commanding all bishops to establish seminaries in their cathedral cities along the lines of the cathedral school at Seville, which had educated Saint Isidore decades earlier. The decree prescribed the study of Greek, Hebrew, and the liberal arts and encouraged interest in law and medicine.[5] The authority of the Council made this education policy obligatory upon all bishops of the Kingdom of the Visigoths. The council granted remarkable position and deference to the king of the Visigoths. The independent Church bound itself in allegiance to the acknowledged king; it said nothing of allegiance to the Bishop of Rome. Death Saint Isidore of Seville died on 4 April 636 after serving more than 32 years as archbishop of Seville. Work Isidore's Latin style in the Etymologiae and elsewhere, though simple and lucid, reveals increasing local Visigothic traditions. Etymologiae Main article: Etymologiae Isidore was the first Christian writer to try to compile a summa of universal knowledge, in his most important work, the Etymologiae (taking its title from the method he uncritically used in the transcription of his era's knowledge). It is also known by classicists as the Origines (the standard abbreviation being Orig). This encyclopedia — the first such Christian epitome—formed a huge compilation of 448 chapters in 20 volumes. In it, as Isidore entered his own terse digest of Roman handbooks, miscellanies and compendia, he continued the trend towards abridgements and summaries that had characterised Roman learning in Late Antiquity. In the process, many fragments of classical learning are preserved which otherwise would have been hopelessly lost; "in fact, in the majority of his works, including the Origines, he contributes little more than the mortar which connects excerpts from other authors, as if he was aware of his deficiencies and had more confidence in the stilus maiorum than his own" his translator Katherine Nell MacFarlane remarks;[6] on the other hand, some of these fragments were lost in the first place because Isidore’s work was so highly regarded—Braulio Page of Etymologiae, Carolingian manuscript (8th century), Brussels, Royal Library of Belgium Isidore of Seville 4 called it quecunque fere sciri debentur, "practically everything that it is necessary to know"—[7] that it superseded the use of many individual works of the classics themselves, which were not recopied and have therefore been lost: "all secular knowledge that was of use to the Christian scholar had been winnowed out and contained in one handy volume; the scholar need search no further".[8] The fame of this work imparted a new impetus to encyclopedic writing, which bore abundant fruit in the subsequent centuries of the Middle Ages. It was the most popular compendium in medieval libraries. It was printed in at least ten editions between 1470 and 1530, showing Isidore's continued popularity in the Renaissance. Until the 12th century brought translations from Arabic sources, Isidore transmitted what western Europeans remembered of the works of Aristotle and other Greeks, although he understood only a limited amount of Greek.[9] The Etymologiae was much copied, particularly into medieval bestiaries.Wikipedia:Citation needed On the Catholic faith against the Jews Isidore's De fide catholica contra Iudaeos furthers Augustine of Hippo's ideas on the Jewish presence in Christian society. Like Augustine, Isidore accepted the necessity of the Jewish presence because of their expected role in the anticipated Second Coming of Christ. In De fide catholica contra Iudaeos, Isidore exceeds the anti-rabbinic polemics of earlier theologians by criticizing Jewish practice as deliberately disingenuous.[10] He contributed two decisions to the Fourth Council of Toledo: Canon 60 calling for the forced removal of children from parents practicing Crypto-Judaism and their education by Christians and Canon 65 forbidding Jews and Christians of Jewish origin from holding public office. Other works Isidore's other works, all in Latin, include: The medieval T-O map represents the inhabited world as described by Isidore in his Etymologiae. • Historia de regibus Gothorum, Vandalorum et Suevorum, a history of the Gothic, Vandal and Suebi kings • his Chronica Majora, a universal history • De differentiis verborum, a brief theological treatise on the doctrine of the Trinity, the nature of Christ, of Paradise, angels, and men • On the Nature of Things, a book of astronomy and natural history dedicated to the Visigothic king Sisebut • Questions on the Old Testament • a mystical treatise on the allegorical meanings of numbers • a number of brief letters • Sententiae libri tres Codex Sang. 228; 9th century[11] • De viris illustribus • De ecclesiasticis officiis Isidore of Seville 5 Legacy Isidore was one of the last of the ancient Christian philosophers; he was the last of the great Latin Church Fathers and was contemporary with Maximus the Confessor. Some consider him to be the most learned man of his age, and he exercised a far-reaching and immeasurable influence on the educational life of the Middle Ages. His contemporary and friend, Braulio of Zaragoza, regarded him as a man raised up by God to save the Iberian peoples from the tidal wave of barbarism that threatened to inundate the ancient civilization of Hispania. The Eighth Council of Toledo (653) recorded its admiration of his character in these glowing terms: "The extraordinary doctor, the latest ornament of the Catholic Church, the most learned man of the latter ages, always to be named with reverence, Isidore". This tribute was endorsed by the Fifteenth Council of Toledo, held in 688. Isidore (right) and Braulio (left) in an Ottonian illuminated manuscript from the 2nd half of the 10th century. Isidore was interred in Seville. His tomb represented an important place of veneration for the Mozarabs during the centuries after the Arab conquest of Visigothic Hispania. In the middle of the 11th century, with the division of Al Andalus into taifas and the strengthening of the Christian holdings in the Iberian peninsula, Fernando I of León found himself in a position to extract tribute from the fractured Arab states. In addition to money, Abbad II al-Mu'tadid, the Abbadid rule of Seville (1042–1069), agreed to turn over St. Isidore's remains to Fernando I.[12] A Catholic poet described al-Mutatid placing a brocaded cover over Isidore's sarcophagus, and remarked, "Now you are leaving here, revered Isidore. You know well how much your fame was mine!" Fernando had Isidore's remains reinterred in the then recently constructed Basilica of San Isidoro in Leon.Wikipedia:Citation needed Isidore was canonized a saint by the Roman Catholic Church in 1598 by Pope Clement VIII and declared a Doctor of the Church in 1722 by Pope Innocent XIII. In Dante's Paradise (X.130), Isidore is mentioned among theologians and Doctors of the Church alongside the Scot Richard of St. Victor and the Englishman Bede the Venerable. The University of Dayton has named their implementation of the Sakai Project in honor of Saint Isidore.[13] Many of his bones are buried in the cathedral of Murcia, Spain. His likeness is used in a trio including Leander of Sevile and Ferdinand III of Castile on Sevilla FC's crest badge. To honour St. Isidore, a modern day knightly order was formed on January 1, 2000. Membership is open to all men and women worldwide. One of the aims of the order is to honour Saint Isidore of Seville as the patron saint on the internet and to promote Christian chivalry through the internet. Members receive a modern day knighthood.[14] References [1] Montalembert, Charles F. Les Moines d'Occident depuis Saint Benoît jusqu'à Saint Bernard [The Monks of the West from Saint Benoit to Saint Bernard]. Paris: J. Lecoffre, 1860. [2] Jacques Fontaine, Isidore de Séville et la culture classique dans l'Espagne wisigothique (Paris) 1959 [3] Roger Collins, Early Medieval Spain. New York: St Martin's Press, 1995, pp. 79-86. [4] "His literary style, though lucid, is pedestrian": Katherine Nell MacFarlane's observation, in "Isidore of Seville on the Pagan Gods (Origines VIII. 11)", Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, New Series, 70.3 (1980):1-40, p. 4, reflects mainstream secular opinion. [5] Isidore's own work regarding medicine is examined by William D. Sharpe, Isidore of Seville: The Medical Writings (Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 54.2) 1964. [6] MacFarlane 1980:4; MacFarlane translates Etymologiae viii. [7] Braulio, Elogium of Isidore appended to Isidore's De viris illustribus, heavily indebted itself to Jerome. [8] MacFarlane 1980:4. [9] St. Isidore of Seville (http:/ / www. newadvent. org/ cathen/ 08186a. htm) [10] , books.google.com Isidore of Seville [11] Cesg.unifr.ch (http:/ / www. cesg. unifr. ch/ cesg-cgi/ kleioc/ g0010/ exec/ pagesmaframe/ "csg-0228_001. jpg"/ segment/ "body") [12] Father Alban Butler. “Saint Isidore, Bishop of Seville”. Lives of the Fathers, Martyrs, and Principal Saints, 1866. Saints.SQPN.com. 2 April 2013. Web. 9 August 2014. Saints SQPN (http:/ / saints. sqpn. com/ butlers-lives-of-the-saints-saint-isidore-bishop-of-seville/ ) [13] Isidore.udayton.edu (http:/ / isidore. udayton. edu) [14] The Order of St. Isidore of Seville (http:/ / www. st-isidore. org). Accessed 28 June 2014. Primary sources • The Etymologiae (http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Isidore/home.html) (complete Latin text) • Barney, Stephen A., Lewis, W. J., Beach, J. A. and Berghof, Oliver (translators). The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006. ISBN 0-521-83749-9, ISBN 978-0-521-83749-1. • Castro Caridad, Eva and Peña Fernández, Francisco (translators). "Isidoro de Sevilla. Sobre la fe católica contra los judíos". Sevilla:Universidad de Sevilla, 2012. ISBN 978-84-472-1432-7. • Throop, Priscilla, (translator). Isidore of Seville's Etymologies. Charlotte, VT: MedievalMS, 2005, 2 vols. ISBN 1-4116-6523-6, 978-1-4116-6523-1; ISBN 1-4116-6526-0, 978-1-4116-6526-1. • Throop, Priscilla, (translator). Isidore's Synonyms and Differences. (a translation of Synonyms or Lamentations of a Sinful Soul, Book of Differences I, and Book of Differences II) Charlotte, VT: MedievalMS, 2012 (EPub ISBN 978-1-105-82667-2) • Online Galleries, History of Science Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries (http://hos.ou.edu/ galleries/03Medieval/Isidore/) High resolution images of works by Isidore of Seville in .jpg and .tiff format. Secondary sources • Henderson, John. The Medieval World of Isidore of Seville: Truth from Words. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007. ISBN 0-521-86740-1. • Herren, Michael. "On the Earliest Irish Acquaintance with Isidore of Seville." Visigothic Spain: New Approaches. James, Edward (ed). Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1980. ISBN 0-19-822543-1. • Englisch, Brigitte. "Die Artes liberales im frühen Mittelalter." Stuttgart, 1994. • Henry Wace, Dictionary of Christian Biography (http://www.ccel.org/w/wace/biodict/htm/TOC.htm), ccel.org • Encyclopædia Britannica, 1911 edition: Isidore of Seville (http://www.1911encyclopedia.org/ Isidore_Of_Seville), 1911encyclopedia.org • "'St. Isidore of Seville" (http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/08186a.htm). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913. Other material • The Order of Saint Isidore of Seville (http://www.st-isidore.org), st-isidore.org • Jones, Peter. "Patron saint of the internet" (http://www.telegraph.co.uk/arts/main.jhtml?xml=/arts/2006/08/ 27/bobar20.xml), telegraph.co.uk., 27 August 2006 (Review of The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville, Cambridge University Press, 2006 (ISBN 0-521-83749-9) • Shachtman, Noah. "Searchin' for the Surfer's Saint" (http://www.wired.com/news/culture/1,49995-0.html), wired.com., 25 January 2002 • SaintIsidoreOfSeville.com (http://www.saintisidoreofseville.com) 6 Isidore of Seville External links • Quotations related to Isidore of Seville at Wikiquote • Works written by or about Isidorus Hispalensis at Wikisource 7 Article Sources and Contributors 8 Article Sources and Contributors Isidore of Seville Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?oldid=623954296 Contributors: 12.31.6.xxx, 1exec1, A bit iffy, AMC0712, Adam Bishop, Aethralis, AidanP02, Aldux, Alex299006, Almaliq, Ambrosius007, AnakngAraw, Anbu121, Andreas Kaganov, AndrewNJ, Andycjp, Anneyh, Antiquary, Antony-22, Arasaka, Arthena, Ashley Y, Attilios, Auntof6, Avjoska, Barbatus, Bede735, Bill Thayer, Billinghurst, Blainster, Bryan Derksen, Buddhaamaatya, Bwpach, Carl.bunderson, CarolusAndreas, Charles Matthews, Chiswick Chap, Chris55, Cmontero, Conversion script, CrazyChemGuy, DBigXray, DO'Neil, Dauwa, Dbachmann, Dclown50, Dimadick, Discospinster, Divineskies, Dlohcierekim, Dufekin, Egmontaz, Elizium23, Esoglou, EstherLois, Evrik, Fauban, FeanorStar7, FinnWiki, FourthAve, Func, Garcilaso, Garing, Gilliam, Grailknighthero, Gwernol, Haeinous, Hailey C. Shannon, Haw81, Headbomb, Hmains, Ianlopez12, Iblardi, Ihcoyc, Isidore, JASpencer, JackofOz, Jacob Haller, Jaraalbe, Jauhienij, Jbribeiro1, JediKnyghte, Jerome Charles Potts, Jlg3926, Jlg4104, JoanneB, John, Johnbod, Jondel, Jonel, Julien1978, K6ka, Kanbun, Kate, Keichwa, Khazar2, Kingpaul, Knowledgge, Koyaanis Qatsi, Krakkos, Leinad-Z, Lima, Liz Henderson, Llywrch, Lockley, Lotje, LovesMacs, Ludi, Luisldq, Lyonski, MichaelTinkler, Mild Bill Hiccup, Miracle Pen, Mlindroo, Naohiro19, Neddyseagoon, Nerissa-Marie, Nighm, Olivier, Omnipaedista, Pastordavid, Paul August, Phe, Philippe, Playclever, Polly, Polylerus, Pratyya Ghosh, R'n'B, RafaAzevedo, RandomCritic, Randy Kryn, Raven in Orbit, Rbraunwa, Red45joe, Renice, Rhinoracer, Rhododendrites, Rholton, Rich Farmbrough, Rkachelriess, Rojypala, Roltz, Ruy Pugliesi, Rwflammang, Sailko, Sbonsor, Schinleber, SchreiberBike, Searchme, Senjuto, Serafín33, Sisebut, Srnec, Staffelde, Stefanomione, SteveSims, Stevenmitchell, Suruena, The Ogre, Thryduulf, Tom harrison, Tomisti, Tony Sidaway, Tucoxn, Tzartzam, Unk3mpt, Vaquero100, Velho, Waacstats, Wareh, Webclient101, Wegesrand, Wesley, West.andrew.g, Wetman, Who, WikHead, William Avery, Wingman4l7, Witger, XPTO, Xandar, Zacatecnik, Zaqarbal, Александър, 221 anonymous edits Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors File:Isidor von Sevilla.jpeg Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Isidor_von_Sevilla.jpeg License: Public Domain Contributors: AndreasPraefcke, Anual, Dionisio, Ecummenic, Enrique Cordero, Evrik, Ixtzib, JMCC1, Ketamino, Kokodyl, Mattes, Schaengel89, Sebastian Wallroth, Svencb Image:Isidoro de Sevilla (José Alcoverro) 01.jpg Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Isidoro_de_Sevilla_(José_Alcoverro)_01.jpg License: Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 2.5 Contributors: Zaqarbal, 1 anonymous edits Image:Isidoro di siviglia, etimologie, fine VIII secolo MSII 4856 Bruxelles, Bibliotheque Royale Albert I, 20x31,50, pagina in scrittura onciale carolina.jpg Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Isidoro_di_siviglia,_etimologie,_fine_VIII_secolo_MSII_4856_Bruxelles,_Bibliotheque_Royale_Albert_I,_20x31,50,_pagina_in_scrittura_onciale_carolina.jpg License: Public Domain Contributors: Sailko Image:Diagrammatic T-O world map - 12th century.jpg Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Diagrammatic_T-O_world_map_-_12th_century.jpg License: Public Domain Contributors: Leinad-Z, Rd232 Image:Meister des Codex 167 001.jpg Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Meister_des_Codex_167_001.jpg License: Public Domain Contributors: AndreasPraefcke, Copydays, Dsmdgold, Goldfritha, Kurpfalzbilder.de, MRB, Mel22 Image:PD-icon.svg Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:PD-icon.svg License: Public Domain Contributors: Alex.muller, Anomie, Anonymous Dissident, CBM, MBisanz, PBS, Quadell, Rocket000, Strangerer, Timotheus Canens, 1 anonymous edits file:Wikiquote-logo.svg Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Wikiquote-logo.svg License: Public Domain Contributors: -xfi-, Dbc334, Doodledoo, Elian, Guillom, Jeffq, Krinkle, Maderibeyza, Majorly, Nishkid64, RedCoat, Rei-artur, Rocket000, 11 anonymous edits File:wikisource-logo.svg Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Wikisource-logo.svg License: logo Contributors: ChrisiPK, Guillom, INeverCry, Jarekt, Leyo, MichaelMaggs, NielsF, Rei-artur, Rocket000, Steinsplitter License Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 //creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/