Allegheny College Revisited: Cardozo

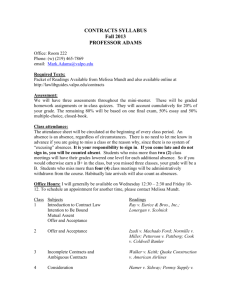

advertisement