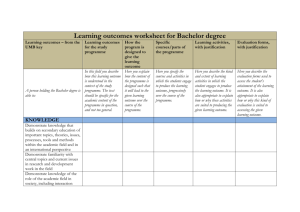

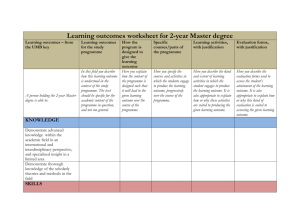

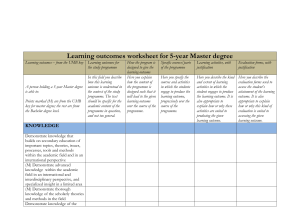

the referencing of the Irish NFQ to the EQF

advertisement