Assignment #9 Solutions

advertisement

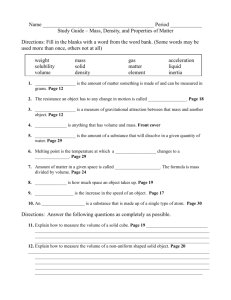

PC235 Winter 2013 Classical Mechanics Assignment #9 Solutions #1 (10 points) JRT Prob. 11.2 A massless spring (force constant k1 ) is suspended from the ceiling, with a mass m1 hanging from its lower end. A second massless spring (force constant k2 ) is suspended from m1 , and a second mass m2 is suspended from the second spring’s lower end. Assuming that the masses move only in a vertical direction and using coordinates y1 and y2 measured from the masses’ equilibrium positions, show that the equations of motion can be written in the matrix form Mÿ = −Ky, where y is the 2 × 1 column made up of y1 and y2 . Find the matrices M and K. Solution Let ŷ1 and ŷ2 be the extensions of the two springs from their unstretched lengths and y10 and y20 be their values at equilibrium. The displacements from equilibrium are y1 = ŷ1 − y10 and y2 = ŷ2 − y20 . (1) The net downward forces on the two masses are F1 = m1 g − k1 ŷ1 + k2 (ŷ2 − ŷ1 ) and F2 = m2 g − k2 (ŷ2 − ŷ1 ), (2) and thus the conditions for equilibrium are m1 g = k1 y10 = k2 (y20 − y10 ) and m2 g = k2 (y20 − y10 ). (3) Now, applying Newton’s 2nd law and using eq. (1) to eliminate ŷ1 and ŷ2 from eq. (2), we find that m1 ÿ1 = F1 = m1 g − k1 (y1 + y10 ) + k2 [y2 − y1 + (y20 − y10 )] = −k1 y1 + k2 (y2 − y1 ) (4) (5) (the equilibrium condition is used to eliminate several terms in the last line.) Similarly, m2 ÿ2 = F2 = m2 g − k2 (ŷ2 − ŷ1 ) = −k2 (y2 − y1 ). (6) 1 The last two results combine to give the matrix equation Mÿ = −Ky, where k1 + k2 −k2 m1 0 and K = M= . (7) −k2 k2 0 m2 #2 (15 points) JRT Prob. 11.10 (a) Write down the equations of motion corresponding to eq. (11.2) for the case of two equal-mass carts with three identical springs, but with each cart subjected to a linear resistive force −bv (same coefficient b for both carts). (b) Show that if you change variables to the normal coordinates ξ1 = 12 (x1 + x2 ) and ξ2 = 12 (x1 − x2 ), the equations of motion for ξ1 and ξ2 are uncoupled. (c) Write down the general solutions for the normal coordinates and hence for x1 and x2 (assume that b is small, so that the oscillations are underdamped.) (d) Find x1 (t) and x2 (t) for the initial conditions x1 (0) = A and x2 (0) = v1 (0) = v2 (0) = 0, and plot them for 0 ≤ t ≤ 10π using the values A = k = m = 1, b = 0.1. Solution (a) As in section 5.4, we define β = b/2m and ω02 = k/m. Then, the equations of motion are ẍ1 = −2β ẋ1 − 2ω02 x1 + ω02 x2 ẍ2 = −2β ẋ2 + ω02 x1 − 2ω02 x2 . (8) (b) If you take first the sum and then the difference of these two equations, you will get the uncoupled equations ξ¨1 = −2β ξ˙1 − ω02 ξ1 and ξ¨2 = −2β ξ˙2 − 3ω02 ξ2 . 2 (9) (c) The equation for ξ1 is exactly the equation (5.28) that we found for a single damped oscillator, and has the solution (5.37), which we can rewrite as q −βt ξ1 (t) = e (B1 cos ω1 t + C1 sin ω1 t), where ω1 = ω02 − β 2 (10) ξ2 (t) = e−βt (B2 cos ω2 t + C2 sin ω2 t), where ω2 = q 3ω02 − β 2 . (11) The expressions for x1 (t) and x2 (t) follow at once by adding and subtracting these expressions for ξ1 (t) and ξ2 (t). (d) The given initial conditions imply that ξ1 (0) = ξ2 (0) = A/2, with both derivatives zero. Therefore, B1 = B2 = A2 , C1 = βA/2ω1 , and C2 = βA/2ω2 , from which we can write down β A −βt cos ω1 t + e sin ω1 t (12) ξ1 (t) = 2 ω1 A −βt β ξ2 (t) = cos ω2 t + e sin ω2 t . (13) 2 ω2 1 0.5 0.5 2 1 0 x x1 The sum and difference of these two functions give us x1 (t) and x2 (t), which are plotted below. −0.5 −1 0 −0.5 0 5 10 15 20 25 −1 30 0 5 10 t 15 20 25 30 t Fig. 1: x1 (t) and x2 (t) for question #2 #3 (15 points) JRT Prob. 11.18 Two equal masses m are constrained to move without friction, one on the positive x axis and one on the positive y axis. They are attached to two identical springs (force constant k) whose other ends are attached to the origin. In addition, the two masses are connected to each other by a third spring of force constant k ′ . The springs are chosen so that the system is 3 in equilibrium with all three springs relaxed (length equal to unstretched length). What are the normal frequencies? Find and describe the normal modes. Consider only small displacements from equilibrium. y L k’ k x k O L Fig. 2: Geometry for Question #3 Solution Let the equilibrium length of the √ first 2 springs be L and that of the one that connects the two masses be 2L. Let x and y be the displacements of the two masses from their equilibrium positions; these will be our two generalized coordinates. The total KE is T = 12 m(ẋ2 + ẏ 2 ) and the total PE is U = 12 k(x2 + y 2 ) + 12 k ′ z 2 , where z is the extension of the diagonal spring (which is a function of x and y; that will take a bit of work to figure out). Since we are interested only in small oscillations, we can write p p √ √ z = (L + x)2 + (L + y)2 − 2L ≈ 2L2 + 2L(x + y) − 2L (14) √ p = 2L 1 + (x + y)/L − 1 (15) √ 1 (16) ≈ 2L · (x + y)/L, 2 where for the last expression on the first line we dropped terms higher than 1st order in x and y and for the final expression we used the binomial expansion for the square root. Therefore, we can write z 2 = (x + y)2 /2, and the 4 total PE is 1 ′ 1 k′ k′ 1 2 2 2 2 2 ′ k+ x + k+ y + k xy . U = k(x + y ) + k (x + y) = 2 4 2 2 2 (17) Writing down Lagrange’s equations for x and y leads to ′ k′ k + k2 m 0 2 and K = M= . (18) ′ k′ 0 m k + k2 2 Next, we set det(K − ω 2 M) = 0, or (mω 2 − k)(mω 2 − k − k ′ ) = 0. Thus, the normal frequencies are r r k k + k′ ω1 = . (19) and ω2 = m m For the first normal mode, solving (K − ω12 M)a = 0 gives a1 = −a2 ; the masses oscillate with equal amplitudes but out of step. In this mode, the diagonal spring’s length remains constant (at least in the small-oscillation approximation), which is why k ′ is irrelevant to ω1 . For the second normal mode, we have a1 = a2 . Here, the masses move with equal amplitudes and both in step (both x and y increase together and decrease together). In this mode, the diagonal spring does stretch and compress; this extra contribution to the PE increases the frequency of oscillations. #4 (10 points) JRT Prob. 11.26 A bead of mass m is threaded on a frictionless circular wire hoop of radius R and mass m. The hoop is suspended at the point A and is free to swing in its own vertical plane as shown in Fig. 11.20 of the text. Using the angles φ1 and φ2 as generalized coordinates, solve for the normal frequencies of small oscillations, and find and describe the motion in the corresponding normal modes. Solution The moment of inertia of the hoop about its edge is I = 2mR2 , so its kinetic energy is 1 (20) T1 = I φ̇21 = mR2 φ̇21 . 2 The velocity of the bead is (for small oscillations) the sum of the velocity of the bead relative to the hoop’s center and the velocity of the hoop’s center 5 relative to the pivot point. Thus, the bead’s speed is equal to R φ̇1 + φ̇2 . The total kinetic energy is therefore 1 (21) T = mR2 3φ̇21 + 2φ̇1 φ̇2 + φ̇22 . 2 The total potential energy is U = U1 + U2 = mgR (1 − cos φ1 ) + mgR [(1 − cos φ1 ) + (1 − cos φ2 )] 1 ≈ mgR 2φ21 + φ22 2 (22) (23) (24) (we attribute the entire mass of the hoop to a point at its CM). Therefore, the matrices are 2 0 3 1 2 2 2 , (25) and K = mR ω0 M = mR 0 1 1 1 where ω02 = g/R. Setting the determinant of K − ω 2 M to zero, we find the normal frequencies 1 ω1 = √ ω0 2 and ω2 = √ 2ω0 . (26) The first leads to the normal mode where the angles oscillate in phase with equal amplitudes. The second leads to the normal mode where the angles oscillate 180 degrees out of phase with the amplitude of φ2 twice that of φ1 . #5 (10 points) JRT Prob. 11.31 Consider a frictionless rigid horizontal hoop of radius R. Onto this hoop I thread three beads with masses 2m, m, and m, and, between the beads, three identical springs, each with force constant k. Solve for the three normal frequencies and find and describe the three normal modes. Solution This problem is best solved using Lagrangian methods. The masses are constrained to move along a circular arc of radius R. Therefore, the speed of 6 mass i is Rφ̇i , and the total kinetic energy is 2 2 2 1 2m Rφ̇1 + m Rφ̇2 + m Rφ̇3 T = 2 1 = mR2 2φ̇21 + φ̇22 + φ̇23 . 2 The three springs contribute to the potential energy. We have 1 2 kR (φ1 − φ2 )2 + (φ2 − φ3 )2 + (φ3 − φ1 )2 U = 2 = kR2 φ21 + φ22 + φ23 − φ1 φ2 − φ2 φ3 − φ3 φ1 . (27) (28) (29) (30) The Lagrangian is then L = T −U (31) 1 = mR2 2φ̇21 + φ̇22 + φ̇23 − kR2 φ21 + φ22 + φ23 − φ1 φ2 − φ2 φ3 − φ3 φ(32) 1 . 2 This leads to the Lagrange’s equations ∂L d ∂L = = −kR2 (2φ1 − φ2 − φ3 ) = 2mR2 φ̈1 ∂φ1 dt ∂ φ˙1 d ∂L ∂L = = −kR2 (−φ1 + 2φ2 − φ3 ) = mR2 φ̈2 ∂φ2 dt ∂ φ˙2 ∂L d ∂L = = −kR2 (−φ1 − φ2 + 2φ3 ) = mR2 φ̈3 . ∂φ3 dt ∂ φ˙3 (33) (34) (35) We can immediately cancel out the R2 terms from all equations. Then, the equations become Mφ̈ = −Kφ, where 2k −k −k 2m 0 0 (36) M = 0 m 0 and K = −k 2k −k . −k −k 2k 0 0 m We then need to find all ω such that det(K−ω 2 M) = 0. We start by dividing this matrix by m and making the substitution k/m = ω02 = 1: 2k − 2mω 2 −k −k −k 2k − mω 2 −k (37) K − ω2M = 2 −k −k 2k − mω 2 2(1 − ω ) −1 −1 −1 2 − ω2 −1 . (38) = −1 −1 2 − ω2 7 The characteristic equation is found by setting the determinant of this matrix to zero. The algebra proceeds as follows: det(K − ω 2 M) = (2 − 2ω 2 ) (2 − ω 2 )2 − 1 + 1 −(2 − ω 2 ) − 1 − 1 1 + (2 − ω 2 ) = (2 − 2ω 2 ) 3 − 4ω 2 + ω 4 − (2 − ω 2 ) − 1 − 1 − (2 − ω 2 ) = (2 − 2ω 2 ) 3 − 4ω 2 + ω 4 − 6 + 2ω 2 = −2(ω 6 − 5ω 4 + 6ω 2 ) =0 (39) This produces the characteristic equation ω 6 − 5ω 4 + 6ω 2 = 0. Since there is no constant term on the left-hand side, one “obvious” normalized frequency is ω1 = 0. Factoring this solutionpout gives us the p quadratic equation ω 4 − 5ω 2 + 6 = 0, which gives us ω2 = 2k/m and ω3 = 3k/m. By substituting ω1 = 0 into the equation (K − ω 2 M)a = 0, we find that a1 = a2 = a3 . That is, the masses move with constant speed around the hoop at their equilibrium separation (and hence none of the springs are ever stretched or compressed thus the zero frequency). For ω2 , we find that a1 = −a2 = −a3 ; here, mass 1 oscillates in one direction while the other two oscillate in the other direction (all amplitudes being equal). For ω3 , a1 = 0 and a2 = −a3 . Here, the heavier mass is stationary while the other two oscillate with equal amplitudes and completely out of phase. These solutions are similar to those found for the linear triatomic molecule in the class notes. #6 (5 points) JRT Prob. 10.15 (a) Write down the integral for the moment of inertia of a uniform cube of side a and mass M , rotating about an edge, and show that it is equal to 23 M a2 . (1 point) (b) If I balance this cube on an edge in unstable equilibrium on a rough table, it will eventually topple and rotate until it hits the table. By considering the energy of the cube, find its angular velocity just before it hits the table. (4 points) Solution (a) This is example 10.2 from the text. For a uniform solid cube rotating around its edge, I = 23 M a2 . 8 (b) The initial energy of the cube is pure PE, since there is no motion. Recall that we calculate the PE of a continuous body by the equivalent notion that its entire mass is located √ at its CM. The CM of a cube is at its center, which is a height a/ 2 above the table when the cube is at equilibrium on its edge. Just before it hits the table, its CM is a/2 above the table. Thus, the change in PE is a M ga √ a ∆U = M g √ − (40) = ( 2 − 1). 2 2 2 This energy has all been converted into rotational kinetic energy, T = 1 Iω 2 . Therefore, 2 1 2 1 M ga √ Iω = M a2 ω 2 = ( 2 − 1) 2 3 2 (41) which is solved to give ω= r 3g √ ( 2 − 1). 2a (42) #7 (10 points) JRT Prob. 10.16 Find the moment of inertia for a uniform cube of mass M and edge a as in Problem 10.15, and then do the following: The cube is sliding with velocity v along a flat horizontal frictionless table when it hits a straight very low step perpendicular to v, and the leading edge comes abruptly to rest. (a) By considering which quantities are conserved before, during, and after the brief collision, find the cube’s angular velocity just after the collision. (b) Find the minimum speed v for which the cube rolls over after hitting the step. Solution (a) The moment of inertia for this cube as it rotates about its edge is shown in example 10.2 (and required in the previous problem); it is I = 32 M a2 . During the collision, it is incorrect to assume that kinetic 9 energy is conserved (it might be an inelastic collision). However, angular momentum is always conserved; in particular the component of L about the edge of the step, which we call Ly (see attached figure). We find that X 5π M av a =− (43) Ly = mα rα ×v = M R×v = M √ v sin 4 2 2 (the negative sign simply indicates that L is directed into the page). Immediately after the collision, the cube is rotating, and we have 2 Ly = Iω0 = M a2 ω0 , 3 (44) where the subscript on ω0 indicates that this is the angular velocity immediately after the collision; ω will decrease over time as the cube tips. Equating these two expressions for Ly (that is, conserving angular 3v momentum), we find that ω0 = 4a . This tells us the angular frequency of the initial rotation as a function of the initial velocity of the cube. (b) To continue this problem, realize that we are running problem JRT1015 in reverse. There, we balanced the cube on its edge (with ω = 0 initially), and calculated ω at the point where it fell on its side. Here, we wish to start with an (unknown) angular velocity that results in ω = 0 at the tipping point. Therefore, q we rewrite our velocity as a √ 3g( 2−1) from that assignment function of ω0 , and substitute ω0 = 2a solution. The resulting velocity is s √ 8ga( 2 − 1) v= . (45) 3 #8 (5 points) JRT Prob. 10.23 Consider a rigid plane body or “lamina,” such as a flat piece of sheet metal, rotating about a point O in the body. If we choose axes so that the lamina lies in the xy plane, which elements of the inertia tensor are automatically zero? Prove that Izz = Ixx + Iyy . Solution 10 Fig. 3: Geometry of question #7 Since the whole body lies in the plane z = 0, the four products of inertia involving z are all zero: Ixz = Iyz = Izx = Izy = 0. For the same reason, X X X Ixx +Iyy = mα (yα2 +zα2 )+ mα (zα2 +x2α ) = mα (x2α +yα2 ) = Izz . (46) #9 (10 points) A rectangular “brick” of mass M is positioned with one corner at the origin and with side lengths a, b, and c in the x−, y−, and z−directions, respectively. (a) Calculate the inertia tensor I with respect to the origin. (10 points) (b) Suppose that the brick is rotating with angular velocity ω, about the y−axis. Find the resulting angular momentum L. (3 points) (c) Discuss whether or not x̂, ŷ, and ẑ constitute a set of principal axes for the brick. (2 points) Solution (a) Note that this is essentially Example 10.2 from the text. We just need to change the limits of integration to account for the fact that we hae a rectangular brick and not a cube. We’ll start with Ixx . Noting that 11 Fig. 4: Geometry for Question #9 ̺ = M/V = M/(abc), we have Ixx = = = = = = = Z a Z b Z c dz̺ y 2 + z 2 dy dx 0 0 0 Z b Z c Ma dy dz y 2 + z 2 abc 0 c 0 Z 1 3 Ma b 2 dy y z + z abc 0 3 0 Z b Ma 1 dy cy 2 + c3 abc 0 3 b M ac 1 3 1 2 y + cy abc 3 3 0 M ac 1 3 1 2 b + cb abc 3 3 M 2 b + c2 . 3 (47) (48) (49) (50) (51) (52) (53) The other two moments of inertia are Iyy = M3 (a2 + c2 ) and Izz = M (c2 + a2 ), as can be found using the same equation (or by observing 3 the symmetries inherent to the problem). 12 As for the products of inertia, we have Z Z b Z a Z b Z c Mc a dx dy xy (54) Ixy = − dx dy dz̺xy = − abc 0 0 0 0 0 b Z Z Mc a Mc a 1 2 1 2 = − (55) xb dx xy dx =− abc 0 2 abc 0 2 0 a 1 Mc 1 2 2 Mc 1 2 2 xb =− a b = − M ab. (56) = − abc 4 abc 4 4 0 By observing the symmetries inherent to the problem (and by recalling that the inertia matrix must be symmetric), we find that Iyx = −M ab/4, Ixz = Izx = −M ac/4, and Iyz = Izy = −M bc/4. Therefore, the inertia matrix can be written 4 (b2 + c2 ) −3ab −3ac M . −3ab 4 (a2 + c2 ) −3bc I= (57) 12 2 2 −3ac −3bc 4 (a + b ) It is easy to verify that if the brick is changed to a cube - that is, if a = b = c, I takes the same form as in example 10.2 of the text. (b) This particular angular momentum can be written ω = (0, ω, 0). Therefore, M ωab M ω (a2 + c2 ) M ωbc . (58) L = Iω = − , ,− 4 3 4 (c) Since rotation about the y−axis does not produce an angular momentum L parallel to ω, it is clear that x̂, ŷ, and ẑ do not constitute a set of principal axes for the brick. You can also claim that this is the case because of the non-zero off-diagonal elements of I. #10 (10 points) JRT Prob. 10.27 Find the inertia tensor for a uniform, thin hollow cone, such as an ice-cream cone, of mass M , height h, and base radius R, spinning about its pointed end. Solution Since this is a thin cone, it has an areal mass density σ (mass/area). All 13 points on the cone can be described by the two cylindrical coordinates ρ and φ (you can use z and φ instead, but it’s very slightly less convenient). Refer to the figure below, and imagine dividing the surface into strips as shown, and then dividing the strips into small increments of angle dφ. Then, the element of area is dA = (dρ/ sin α)(ρ dφ), where α is the half-angle of the cone. The moment about the z axis is therefore Z Z R Z 2π ρ dρ dφ σπR4 2 2 Izz = σ(x + y )dA = σ ρ2 = , (59) sin α 2 sin α 0 0 since the φ integral evaluates to 2π and the ρ integral evaluates to R4 /4. 2 The area of the cone can check this by performing R is A = πR / sin α (you 2 the integral A = dA). Therefore, σπR / sin α = M , the total mass. All together, we have Izz = M R2 /2. The other two moments, Ixx and Iyy , must be identical by symmetry. For the first of these, Z Ixx = σ(y 2 + z 2 )dA. (60) The first term here is the same as the second term in Izz . Since the two terms in Izz are equal (again, by symmetry), we conclude that the first term in Ixx is equal to Izz /2. In the second term of Ixx we can replace z by ρh/R, from which we see that the second term in Ixx is h2 /R2 times Izz . All together, we find that 1 1 h2 Ixx = Iyy = (61) + 2 Izz = M (R2 + 2h2 ). 2 R 4 Finally, all of the off-diagonal terms in I are zero by rotational symmetry about the z axis (as was the case with the solid cone). Therefore, (R2 + 2h2 ) 0 0 M 0 (R2 + 2h2 ) 0 . I= (62) 4 0 0 2R2 #11 (10 points) JRT Prob. 10.36 A rigid body consists of three equal masses (m) fastened at the positions (a, 0, 0), (0, a, 2a), and (0, 2a, a). (a) Find the inertia tensor I. 14 Fig. 5: Geometry of question #10 (b) Find the principal moments and a set of orthogonal principal axes. Solution (a) The three masses are equal (m1 = m2 = m3 = m) and their positions are r1 = a(1, 0, 0), r2 = a(0, 1, 2), r3 = a(0, 2, 1). Therefore, X Ixx = mα (yα2 + zα2 ) = ma2 (0 + 5 + 5) = 10ma2 (63) X Iyy = mα (x2α + zα2 ) = ma2 (1 + 4 + 1) = 6ma2 (64) X Izz = mα (x2α + yα2 ) = ma2 (1 + 1 + 4) = 6ma2 (65) X Ixy = − mα xα yα = −ma2 (0 + 0 + 0) = 0 (66) X Ixz = − mα xα zα = −ma2 (0 + 0 + 0) = 0 (67) X Iyz = − mα yα zα = −ma2 (0 + 2 + 2) = −4ma2 . (68) That is, 5 0 0 3 −2 . I = 2ma2 0 0 −2 3 15 (69) (b) The characteristic equation is det(I − λ1) = (10ma2 − λ)2 (2ma2 − λ) = 0. (70) Therefore, the principal moments are λ1 = λ2 = 10ma2 and λ3 = 2ma2 . If we set λ = 10ma2 , the equation (I−λ1)ω = 0 yields three equations: 0 = 0, ω2 + ω3 = 0, and ω2 + ω3 = 0. This tells us that ω2 = −ω3 , and that the two normalized eigenvectors corresponding to λ = 10ma2 are e1 = (1, 0, 0), 1 and e2 = √ (0, 1, −1) 2 (71) (note that any two perpendicular directions in the plane defined by e1 and e2 are also suitable principal axes.) Setting λ = 2ma2 , the equation (I − λ1)ω = 0 yields three equations, ω1 = 0, ω2 − ω3 = 0, and −ω2 + ω3 = 0. When normalized, this defines the principal axis 1 e3 = √ (0, 1, 1). (72) 2 16