High Precision Measurements of Non-Mass

advertisement

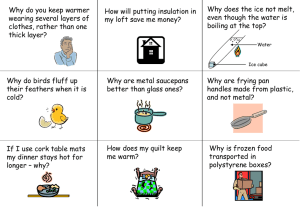

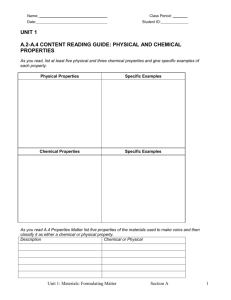

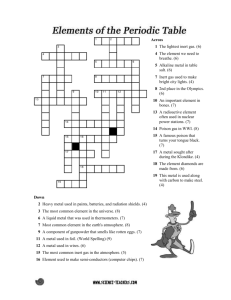

Anal. Chem. 2006, 78, 8477-8484 High Precision Measurements of Non-Mass-Dependent Effects in Nickel Isotopes in Meteoritic Metal via Multicollector ICPMS David L. Cook,*,†,‡,§ Meenakshi Wadhwa,†,‡,§ Philip E. Janney,§ Nicolas Dauphas,†,‡,⊥ Robert N. Clayton,†,‡,⊥ and Andrew M. Davis†,‡,⊥ Department of the Geophysical Sciences, The University of Chicago, 5734 South Ellis Avenue, Chicago, Illinois 60637, Chicago Center for Cosmochemistry, 5640 South Ellis Avenue, Chicago, Illinois 60637, Department of Geology, The Field Museum, 1400 South Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, Illinois 60605, and Enrico Fermi Institute, 5640 South Ellis Avenue, Chicago, Illinois 60637. We measured the Ni isotopic composition of metal from a variety of meteorite groups to search for variations in the 60Ni abundance from the decay of the short-lived nuclide 60Fe (t1/2 ) 1.49 My) and for possible nucleosynthetic effects in the other stable isotopes of Ni. We developed a high-yield Ni separation procedure based on a combination of anion and cation exchange chromatography. Nickel isotopes were measured on a single-focusing, multicollector, inductively coupled mass spectrometer (MC-ICPMS). The external precision on the massbias-corrected 60Ni/58Ni ratio ((0.15 E; 2σ) is comparable to similar studies using double-focusing MC-ICPMS. We report the first high-precision data for 64Ni, the least abundant Ni isotope, obtained via MC-ICPMS. The external precision on the mass-bias-corrected 64Ni/58Ni ratio ((1.5 E; 2σ) is better than previous studies using thermal ionization mass spectrometry. No resolvable excesses relative to a terrestrial standard in the mass-bias-corrected 60Ni/58Ni ratio were detected in any meteoritic metal samples. However, resolvable deficits in this ratio were measured in the metal from several unequilibrated chondrites, implying a 60Fe/56Fe ratio of ∼1 × 10-6 at the time of Fe/Ni fractionation in chondritic metal. A 60Fe/56Fe ratio of (4.6 ( 3.3) × 10-7 is inferred at the time of Fe/ Ni fractionation on the parent bodies of magmatic iron meteorites and pallasites. No clearly resolvable non-massdependent anomalies were detected in the other stable isotopes of Ni in the samples investigated here, indicating that the Ni isotopic composition in the early solar system was homogeneous (at least at the level of precision reported here) at the time of meteoritic metal formation. Meteorites provide a record of events and processes that occurred during the formation and early evolution of the solar system. Various phases in undifferentiated meteorites (e.g., ordinary and carbonaceous chondrites) contain information on * Towhomcorrespondenceshouldbeaddressed.E-mail: davecook@uchicago.edu. † The University of Chicago. ‡ Chicago Center for Cosmochemistry. § The Field Museum. ⊥ Enrico Fermi Institute. 10.1021/ac061285m CCC: $33.50 Published on Web 11/15/2006 © 2006 American Chemical Society nebular processes, such as condensation, and on parent body processes, such as accretion, metamorphism, and aqueous alteration. These primitive meteorites may also provide a record of the precursor materials (e.g., presolar dust grains) involved in the formation of the solar nebula. Differentiated meteorites (e.g., eucrites, pallasites, and iron meteorites) record diverse parent body processes, such as silicate differentiation and core formation. Constraining the timing of these processes is critical for unraveling early solar system history. The isotopic record left by the former presence of short-lived, now extinct, radionuclides in meteorites can provide chronometric data for this early period. Chronometry based on a number of extinct radionuclides has been applied to meteoritic materials.1,2 The precision of ages based on short-lived chronometers is typically better than 1 My, which makes them ideally suited to studying the timing of early solar system processes.1,2 Unambiguous evidence of excesses in radiogenic 60Ni from the decay of 60Fe (t1/2 ) 1.49 My) was first reported in bulk eucrite samples.3,4 Since then, analyses of various phases in unequilibrated chondrites have revealed 60Ni excesses in sulfides, oxides, and silicates.5-8 Recently, 60Ni excesses of up to 1.5 were reported for Fe-Ni metal from several iron meteorites9 and ordinary chondrites;10 these were the first reports of excess 60Ni in meteoritic metal. The metal phase in meteorites may have been subjected to both nebular and parent body processes, such as condensation, oxidation, melting, metal-silicate segregation, and core crystallization.11 To date, only the 107Pd-107Ag 12,13 (t1/2 ) 6.5 (1) McKeegan, K. D.; Davis, A. M. In Treatise on Geochemistry; Davis, A. M., Ed.; Elsevier Pergamon: San Diego, CA, 2004; Vol. 1, pp 431-460. (2) Gilmour, J. D. Space Sci. Rev. 2000, 92, 123-132. (3) Shukolyukov, A.; Lugmair, G. W. Science 1993, 259, 1138-1142. (4) Shukolyukov, A.; Lugmair, G. W. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 1993, 119, 159166. (5) Tachibana, S.; Huss, G. R. Astrophys. J. 2003, 588, L41-L44. (6) Guan, Y.; Huss, G. R.; Leshin, L. A.; MacPherson, G. J. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 2003, 38, A138. (7) Mostefaoui, S.; Lugmair, G. W.; Hoppe, P. Astrophys. J. 2005, 211, 271277. (8) Tachibana, S.; Huss, G. R.; Kita, N. T.; Shimoda, G.; Morishita, Y. Astrophys. J. 2006, 639, L87-L90. (9) Moynier, F.; Telouk, P.; Blichert-Toft, J.; Albarède, F. Lunar Planet Sci. 2004, 35, no. 1286. (10) Moynier, F.; Blichert-Toft; J.; Telouk; P.; Albarède, F. Lunar Planet Sci. 2005, 36, no. 1593. Analytical Chemistry, Vol. 78, No. 24, December 15, 2006 8477 My) and 182Hf-182W 14-17 (t1/2 ) 8.9 My) chronometers have been applied toward obtaining high-resolution chronology of metal samples. The findings of Moynier et al.9,10 suggested that the 60Fe-60Ni chronometer may add a tool for deciphering the history of meteoritic metal. The resolution of small time differences and of non-massdependent isotopic anomalies (possibly of nucleosynthetic origin) using short-lived chronometers requires isotope measurements of high precision. Nickel isotopes have been measured using secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS),5-8 thermal ionization mass spectrometry (TIMS),3,4,18-20 and multicollector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (MC-ICPMS).9,10,21 Analyses using SIMS can provide high spatial resolution (e.g., 5 µm) but suffer from relatively poor precision.5-8 Isobaric interferences on 58Ni by 58Fe and on 64Ni by 64Zn in SIMS analyses make it difficult to measure these Ni isotopes. Thus, the full complement of Ni isotopes (58Ni, 60Ni, 61Ni, 62Ni, 64Ni) cannot be easily determined using this technique. Analysis via chemical separation and purification of Ni followed by TIMS allows for the measurement of all five Ni isotopes and for the correction of 58Fe and 64Zn interferences. The typical precision of the isotope ratio measurements by this technique is better than by SIMS: a precision on 60Ni/58Ni, the ratio used for chronology, as good as ( 0.6 (2σ) has been achieved.3 However, precisions on the other Ni isotope ratios are on the order of at least several epsilon units.18-20 Like TIMS, MC-ICPMS also provides the ability to measure all Ni isotopes and correct for interferences from 58Fe and 64Zn. Additionally, significantly better precision on all Ni isotope ratios may be possible. Thus far, high-precision Ni isotope ratio measurements have been made only on double-focusing MC-ICPMS instruments.9,10,21 We report the first highly precise and accurate measurements of Ni isotopes using a single-focusing MC-ICPMS. This instrument employs a hexapole collision cell to thermalize ions and remove interfering polyatomic species. The external precision of Ni isotope ratio measurements with this technique is comparable to or better than that of prior work.9,10,21 On the basis of high precision analyses of Ni isotopes in metal from a variety of undifferentiated and differentiated meteorites using this technique, we present implications for the initial abundance of 60Fe and for the degree of Ni isotopic homogeneity in the early solar system. EXPERIMENTAL METHODS Samples and Sample Preparation. Samples were chosen to represent a wide variety of meteorite classes,22 including magmatic (IIA, IIB, IID, IIIA, IIIB, IVA, and IVB) and nonmagmatic (IAB and IIICD) iron meteorites, pallasites (main group and (11) Kelly, W. R.; Larimer, J. W. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1977, 41, 93-111. (12) Chen, J. H.; Wasserburg, G. J. Geophys. Monogr. 1996, 95, 1-20. (13) Carlson, C. W.; Hauri, E. H. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2001, 65, 18391848. (14) Lee, D.-C.; Halliday, A. N. Science 1996, 274, 1876-1879. (15) Horan, M. F.; Smoliar, M. I.; Walker, R. J. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1998, 62, 545-554. (16) Lee, D. C. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 2005, 237, 21-32. (17) Markowski, A.; Quitté, G; Halliday, A. N.; Kleine, T. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 2006, 242, 1-15. (18) Morand, P.; Allègre, C. J. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 1983, 63, 167-176. (19) Shimamura, T.; Lugmair, G. W. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 1983, 63, 177-188. (20) Birck, J. L.; Lugmair, G. W. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 1988, 90, 131-143. (21) Quitté, G; Meier, M.; Latkoczy, C.; Halliday, A. N.; Günther, D. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 2006, 242, 16-25. 8478 Analytical Chemistry, Vol. 78, No. 24, December 15, 2006 Eagle Station), and chondrites (LL, H, EH, CR, and CBa). Small pieces (<50 mg) of fresh metal were cut from iron meteorites, pallasites, and terrestrial josephinite (a naturally occurring FeNi metal) using a slow-speed saw with a diamond wafering blade. Samples were examined under a binocular microscope, and any rusty surfaces were mechanically cleaned by polishing with silicon carbide. Sample sizes for chondrites were determined on the basis of the metal content and ranged from 12.5 to 104 mg. The chondrite samples were crushed with a boron carbide mortar and pestle. These crushed samples were passed through a series of sieves, the size fractions greater than 75 µm were combined, and the metal was separated with a hand magnet. The metal separates were rinsed twice with acetone and allowed to dry. A metal globule from the chondrite Gujba was sampled and processed in a manner similar to the iron meteorites. Sample Digestion. Chondrite metal and two pallasite samples (Albin and Molong) that contained visible silicate inclusions were first digested for 24 h on a hot plate at 90 °C in 15-mL Teflon beakers containing 5 mL of 1.0 M HCl. Next, the solutions were centrifuged for 30 min to separate any silicate grains, and the supernatant containing the dissolved metal was removed after centrifugation and evaporated to dryness. Finally, 3 mL of reverse aqua regia (2:1 conc HNO3 to conc HCl) was added to these dried samples, which were then redigested by heating at 120 °C for 24 h. The other two pallasites, all iron meteorites, and the josephinite samples were digested directly by treatment with 3 mL of reverse aqua regia for 24 h at 120 °C. Following digestion in reverse aqua regia, all the samples were evaporated to dryness; equilibrated for several hours in concentrated HCl; evaporated to dryness again; and finally, dissolved in 6 M HCl. This solution was split into two aliquots, one for chemical separation of Ni and another for Fe/Ni elemental ratio measurements. Chemical Separation of Nickel. Nickel was separated from the matrix using a combination of anion and cation exchange chromatography. Nickel was first separated on an anion exchange column.23 Disposable Bio-Rad Poly-Prep columns were packed with 1 mL of AG1-X8 anion resin (200-400 mesh). The columns were washed and conditioned with the following: 10 mL of H2O, 5 mL of 1 M HNO3, 10 mL of H2O, 10 mL of 0.4 M HCl, and 3 mL of 6 M HCl. The sample was loaded in 0.2 mL of 6 M HCl, and Ni was eluted with an additional 6 mL of 6 M HCl in a sequence of 0.5, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, and 2.0 mL. At this molarity, Fe partitions strongly onto the resin, whereas Ni is not retained,24 providing efficient separation of these two elements. The eluted Ni fraction was taken to dryness and then dissolved in 0.2 mL of 6 M HCl. Nickel was further purified on a cation-exchange column. A protocol was developed on the basis of the behavior of Ni in an acetone-HCl medium.25,26 Disposable Bio-Rad Poly-Prep columns were packed with 2 mL of AG50W-X4 cation resin (200-400 mesh). The columns were washed and conditioned with the following: 10 mL of H2O, 10 mL of 4 M HCl, 10 mL of H2O, 6 mL (22) Krot, A. N.; Keil, K.; Goodrich, C. A.; Scott, E. R. D. In Treatise on Geochemistry; Davis, A. M., Ed.; Elsevier Pergamon: San Diego, CA, 2004; Vol. 1, pp 83-128. (23) Dauphas, N.; Janney, P. E.; Mendybaev, R. A.; Wadhwa, M.; Richter, F. M.; Davis, A. M.; Hines, R.; Foley, C. N. Anal. Chem. 2004, 76, 5855-5863. (24) Helfferich, F. G. Ion Exchange; McGraw Hill: New York, 1962. (25) Korkisch, J.; Ahluwalia, S. S. Talanta 1967, 14, 155-170. (26) Strelow, F. W. E.; Victor, A. H.; van Zyl, C. R.; Eloff, C. Anal. Chem. 1971, 43, 870-876. of 30% H2O/70% acetone, and 6 mL of 0.6 M HCl/90% acetone. The sample was loaded in 2 mL 0.6 M HCl/90% acetone, and the column was washed with an additional 4 mL of 0.6 M HCl/90% acetone. Nickel was eluted with 6 mL of 4 M HCl in a sequence of 0.5, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, and 2.0 mL. In the above mixture of HCl and acetone, Ni partitions onto the resin (Kd > 227), whereas the interfering elements Fe and Zn do not (Kd < 1).25 One advantage of this method is that it removes both ferrous and ferric Fe,26 whereas only ferric Fe is removed by the anion column procedure.24 Furthermore, several elements present in meteoritic metal that may not be effectively separated (e.g., Co, Cu), or are not separated at all (e.g., Mn), on the anion column24 are separated on the cation column.25 It is important to cap the column once reagents containing acetone are introduced in order to prevent acetone evaporation, which could lead to a change in the partitioning behavior of the elements.25 A third anion exchange column was employed for some samples to remove any Ti that may be present. Titanium, being a lithophile element, is not expected to be present in any significant amounts in metallic samples. However, metal samples containing inclusions of silicate (i.e., pallasites) or hosted in a silicate matrix (i.e., chondrites) could include a minor amount of silicate that, although it would not significantly affect the Ni (which is a major element in the metal but only a trace element in the silicates), could contribute some Ti. Interferences on 62Ni and 64Ni by TiO species can occur. Because it is not possible to easily monitor and correct for interferences from TiO species during the isotopic analysis, it is imperative that the sample solutions be free from Ti. Therefore, the metal from the pallasites Albin and Molong and all chondrite samples were subjected to a third column exchange separation. Disposable Bio-Rad Poly-Prep columns were packed with 1 mL of AG1-X8 anion resin (200-400 mesh). The columns were washed and conditioned with the following: 10 mL of H2O, 5 mL of 1 M HNO3, 10 mL of H2O, 10 mL of 0.4 M HCl, 5 mL of H2O, and 5 mL of an 0.5 M HF/1 M HCl mixture. The sample was loaded in 0.2 mL of 0.5 M HF/1 M HCl, and Ni was eluted with an additional 3 mL of 0.5 M HF/1 M HCl in a sequence of 0.5, 0.5, 1.0, and1.0 mL. Tests showed that under these conditions, Ni was quantitatively recovered, and Ti was fully retained by the resin. The total procedural blank (≈3 ng) is insignificant compared to the amount of Ni in the samples. Iron/Ni Elemental Ratio Measurements. The Fe/Ni ratios were determined in sample solutions using a Varian ICPMS instrument equipped with a quadrupole mass analyzer at the Field Museum. An aliquot of digested but chemically unprocessed sample was dried and then dissolved in 3% HNO3. A known amount of a manganese concentration standard was added to the sample solution and served as an internal standard. The isotopes 55Mn, 57Fe, and 60Ni were measured, and Fe and Ni concentrations were calculated using calibration curves obtained with external standards. Each aliquot was measured three times, and the uncertainty represents the 2σ standard deviation of all measurements. Nickel Isotopic Measurements. Nickel isotopic measurements were performed at the Isotope Geochemistry Laboratory of the Field Museum on a Micromass (now GV Instruments) IsoProbe MC-ICPMS. This instrument has nine Faraday collectors; Table 1. The Ni Isotopic Compositions of Chemically Processed Aliquots of the Ni Isotopic Standard SRM 986 and of Terrestrial Josephinite sample 60 ( 2σ 61 ( 2σ 64 ( 2σ n SRM no. 1 SRM no. 2 SRM no. 3 Josephinite no. 1 Josephinite no. 2 2-Column Chemistry -0.05 ( 0.27 0.19 ( 1.12 -0.06 ( 0.16 -0.67 ( 2.21 -0.04 ( 0.40 0.05 ( 1.74 -0.15 ( 0.11 0.58 ( 0.72 0.16 ( 0.29 0.27 ( 0.72 2.3 ( 4.4 1.4 ( 1.7 0.4 ( 1.6 0.4 ( 2.0 2.6 ( 2.0 5 5 5 9 5 SRM no. 1 SRM no. 2 SRM no. 3 Josephinite no. 1 Josephinite no. 2 3-Column Chemistry -0.01 ( 0.43 -0.64 ( 1.16 -0.01 ( 0.20 -0.60 ( 0.87 0.12 ( 0.14 0.17 ( 1.89 -0.08 ( 0.06 0.71 ( 0.48 -0.12 ( 0.06 -0.05 ( 0.37 0.0 ( 3.2 1.3 ( 2.0 0.0 ( 2.6 0.6 ( 0.7 0.2 ( 0.6 5 5 5 14 13 thus, all Ni isotopes can be measured simultaneously, and 57Fe and 66Zn can be monitored and used to correct for isobaric interferences on 58Ni from 58Fe (0.28 atom % of total Fe) and on 64Ni from 64Zn (49.18 atom % of total Zn). The sample solution (1 ppm in 3 wt % HNO3) was introduced through a PFA Teflon nebulizer (100 µL/min) in a Cetac Aridus desolvating system using a PFA spray chamber heated to 95 °C. Argon and N2 were introduced into the desolvating system at approximately 3 L min-1 and 35 µL min-1, respectively. Argon was introduced into the collision cell at 1.8 mL min-1 as a thermalizing collision gas. The instrument was optimized to obtain a signal of g6.0 V on 58Ni when running a 1 ppm Ni solution. This generates a signal of g100 mV on 64Ni, the least abundant Ni isotope (0.925%).27 Sampler and skimmer cones made of Ni were used because they were found to provide better signal stability than Al cones. Despite the use of Ni cones, the background signal is negligibly small (1-3 mV on 58Ni) compared to the sample signal. Samples were measured via the standard-sample bracketing technique using the NIST SRM 986 as the Ni isotope standard. SRM 986 is the only commercially available Ni standard with a certified isotopic composition.27 Samples were corrected for mass bias using an exponential law and 62Ni/58Ni ≡ 0.053388.27 The analytical protocol consisted of alternating between standard and sample solutions, with each being measured for 200 s (admittance delay 2 min). Each 200-s measurement (consisting of 20 cycles of 10-s integrations) was preceded by 4 min of washout and an on-peak blank measurement consisting of a 60-s integration measurement while aspirating a clean 3 wt % HNO3 solution. Each reported datum comprises the mean of a minimum of five repeat measurements. Precision and Accuracy. All isotope ratio data (Tables 1 and 2) are reported in units, given as i ) [(Rsample - Rstandard)/Rstandard] × 104, where R is the mass-bias-corrected iNi/58Ni ratio (i ) 60, 61, or 64). Internal precisions for individual samples represent the standard error of the mean (2σm). The external precision was determined by repeated analyses of an Aesar Ni concentration standard over a 24-month period. The mean values of the isotopic ratios from each analysis of the Aesar Ni solution were calculated from five repeat measurements. These mean values for all ratios are identical to SRM 986 within uncertainty. Figure 1 shows these data for the mass-bias-corrected 60Ni/58Ni ratio in epsilon units (27) Gramlich, J. W.; Machlan, L. A.; Barnes, I. L.; Paulsen, P. J. J. Res. Natl. Bur. Stand. (US) 1989, 94, 347-356. Analytical Chemistry, Vol. 78, No. 24, December 15, 2006 8479 Table 2. The 56Fe/58Ni sample Ratios and Ni Isotopic Compositions of Meteoritic Metal group 56Fe/58Ni ( 2σ 60 ( 2σ 61 ( 2σ 64 ( 2σ n Renazzo Gujba Semarkona Bishunpur Forest Vale Indarch CR CBa LL 3.0 LL 3.1 H4 EH4 21.9 ( 0.3 22.0 ( 0.2 14.4 ( 0.2 18.4 ( 0.1 16.4 ( 0.3 18.3 ( 0.5 -0.23 ( 0.10 -0.23 ( 0.08 -0.25 ( 0.10 0.01 ( 0.25 0.07 ( 0.30 -0.13 ( 0.20 0.31 ( 0.54 -0.33 ( 0.33 0.98 ( 0.23 0.32 ( 1.26 -0.05 ( 1.86 0.47 ( 1.29 0.1 ( 0.8 -0.2 ( 0.7 -0.3 ( 0.7 -0.7 ( 1.7 0.0 ( 2.0 0.3 ( 4.0 14 13 10 5 5 5 Eagle Station Albin Brenham Molong PES PMG PMG PMG 7.16 ( 0.09 14.3 ( 0.2 10.3 ( 0.1 11.4 ( 0.1 -0.12 ( 0.12 0.04 ( 0.17 -0.02 ( 0.26 -0.06 ( 0.13 0.39 ( 0.62 -0.53 ( 0.70 0.23 ( 1.22 0.17 ( 0.76 2.0 ( 1.6 0.8 ( 1.3 1.8 ( 4.1 0.0 ( 1.9 5 9 5 5 Coahuila Santa Luzia Carbo Bella Roca Casas Grandes Henbury Gibeon Yanhuitlan Cape of Good Hope Hoba Tlacotepec IIAB IIAB IID IIIAB IIIAB IIIAB IVA IVA IVB IVB IVB 23.1 ( 0.1 19.9 ( 0.3 12.6 ( 0.2 12.4 ( 0.2 17.2 ( 0.3 17.5 ( 0.2 15.9 ( 0.2 16.9 ( 0.3 7.27 ( 0.10 7.01 ( 0.07 7.17 ( 0.03 0.00 ( 0.14 0.05 ( 0.10 -0.08 ( 0.25 0.03 ( 0.17 0.02 ( 0.09 -0.01 ( 0.12 -0.13 ( 0.19 0.00 ( 0.36 -0.13 ( 0.39 -0.21 ( 0.07 -0.18 ( 0.20 0.41 ( 1.45 0.06 ( 0.55 -0.07 ( 1.06 0.26 ( 1.23 0.00 ( 0.36 -0.04 ( 0.35 -0.02 ( 1.86 0.82 ( 0.95 0.11 ( 2.30 -0.21 ( 0.44 -0.15 ( 0.76 1.0 ( 3.4 1.5 ( 1.0 -0.3 ( 2.1 -1.0 ( 0.7 1.4 ( 1.1 -0.4 ( 0.6 2.2 ( 1.7 -0.1 ( 2.9 1.9 ( 1.2 -0.1 ( 0.7 0.3 ( 0.9 5 10 5 8 14 14 5 5 5 13 9 Canyon Diablo Toluca Dayton Mundrabilla IAB IAB IIICD IIICD 18.6 ( 0.3 19.7 ( 0.3 7.08 ( 0.05 16.2 ( 0.4 0.06 ( 0.07 -0.06 ( 0.09 0.08 ( 0.21 -0.12 ( 0.08 0.14 ( 0.58 -0.02 ( 0.34 -0.13 ( 0.75 -0.01 ( 0.47 1.9 ( 0.8 0.3 ( 0.7 2.3 ( 3.2 0.2 ( 0.5 19 15 5 15 Figure 1. 60 values for repeated analyses of an Aesar Ni solution over the course of a 24-month period. Each datum represents the mean of five repeat measurements performed during a single analysis session. The individual error bars are 2σm errors, based on the five repeat measurements for each datum. The external precision is the standard deviation (2σ) based on all of the data plotted here and is shown by the two dashed lines ((0.15 ). (60); the external precision (2σ) is (0.15 . The external precisions for the 61 and 64 values are (0.85 and (1.5 , respectively (Figures S-1 and S-2). Gramlich et al.28 measured terrestrial sulfides and metals and showed that the mass-bias-corrected Ni isotopic compositions of terrestrial samples do not deviate from those of SRM 986. Three aliquots of SRM 986 were processed using our Ni separation chemistry, both with and without the final cleanup column for Ti. Two samples of terrestrial josephinite were also processed using both procedures. As expected, the mean values for all ratios are identical to SRM 986 within uncertainty (Table 1). Figure 2 shows these data for the mass-bias-corrected 60Ni/58Ni ratios in epsilon (28) Gramlich, J. W.; Beary, E. S.; Machlan, L. A.; Barnes, I. L. J. Res. Natl. Bur. Stand. (US) 1989, 94, 357-362. 8480 Analytical Chemistry, Vol. 78, No. 24, December 15, 2006 Figure 2. 60 values for SRM 986 (circles) and terrestrial josephinite (triangles) processed through Ni separation chemistry; filled symbols included the Ti cleanup column. Plotted errors are 2σm; the external precision (2σ) is shown by the two dashed lines ((0.15 ). Smaller error bars on some josephinite samples reflect a larger number of repeat measurements (Table 1). units (60). These data confirm that our Ni separation chemistry for metallic samples does not introduce any analytical artifacts and demonstrate our ability to precisely and accurately measure the Ni isotopic compositions of such samples. Effects of Fe and Zn. As previously noted, Fe and Zn isotopes interfere with Ni isotopes, and these interferences must be corrected for when present. To test our ability to correct for these interferences, we doped aliquots of SRM 986 with varying concentrations of Fe and Zn (four aliquots each). Samples were corrected for Fe and Zn interferences using 58Fe/57Fe ≡ 0.1330 and 64Zn/66Zn ≡ 1.7698. Because all Ni isotopes are normalized to 58Ni, an interference from 58Fe has the potential to affect all of the measured Ni ratios. Figure 3 shows the interference-corrected 60 values for the SRM 986 aliquots doped with Fe as well as an undoped aliquot. These data show that the Fe interference Figure 3. 60 vs the Fe/Ni elemental ratio. Data are from analyses of four aliquots of SRM 986 doped with varying amounts of Fe and one undoped aliquot (Fe/Ni ≈ 10-4). Plotted errors are 2σm; the external precision (2σ) is shown by the two dashed lines ((0.15 ). Figure 5. 60 vs the ratio of the sample-to-standard signal intensity. Data are from analyses of five aliquots of SRM 986 diluted to various concentrations and one undiluted aliquot (ratio ) 1). Plotted errors are 2σm; the external precision (2σ) is shown by the two dashed lines ((0.15 ). the Aesar solutions differed from the standard by 10% or less. All measured sample solutions had signal intensities within 15% of the standard signal intensity, and 95% of those were within 10%. These discrepancies in standard-sample concentration matching are well within the range investigated and do not affect our measurements. Figure 4. 64 vs the Zn/Ni elemental ratio. Data are from analyses of four aliquots of SRM 986 doped with varying amounts of Zn and one undoped aliquot (Zn/Ni ≈ 10-5). Note the scale break on the y axis. Plotted errors are 2σm; the external precision (2σ) is shown by the two dashed lines ((1.5 ). correction is effective, even at high Fe concentrations (i.e., Fe/ Ni ) 0.1). Additionally, no resolvable effects were observed on 61 or 64 due to the presence of Fe. Figure 4 shows the interference-corrected 64 values for the SRM 986 aliquots doped with Zn as well as an undoped aliquot. These data show that the Zn interference correction is not effective for Zn/Ni g 0.01 and illustrate the importance of separating Ni from Zn during chemical processing. For all the samples processed through Ni separation chemistry, the Fe/Ni and Zn/Ni ratios (<3.7 × 10-2 and <4.5 × 10-4, respectively) were substantially below the values for which the interference corrections become ineffective. Therefore, our chemical separation procedure for metallic samples provides Ni with the purity required for accurate isotope measurements. Effects of Signal Intensity. To determine whether differences between the Ni signal intensities for standard and sample solutions can affect our measurements and the level to which samplestandard concentration matching would be required, we analyzed five aliquots of SRM 986 with varying Ni concentrations plus one undiluted aliquot (i.e., 1 ppm) bracketed with a 1 ppm SRM 986 solution. No resolvable effects were observed for any of the Ni isotope ratios, even when the sample signal differed from the standard signal by 45%. Figure 5 shows 60 values from these measurements. All measured Aesar solutions (Figure 1) had signal intensities within 26% of the standard signal intensity, and 95% of RESULTS AND DISCUSSION Table 2 lists the Ni isotopic compositions, given in epsilon units, of the meteoritic metal samples analyzed in this study and the number of repeat measurements (n) made for each sample. Also listed are the measured 56Fe/58Ni ratios for each sample. In the following discussion, we will only consider those deviations in ,60 61, and 64 values to be “resolvable” if they are outside of either the 3σm error or the 2σ external precision, whichever is larger. Possible Nucleosynthetic Anomalies in Ni Isotopes in Meteoritic Metal. Isotopic anomalies of nucleosynthetic origin may be preserved in meteoritic metal. Anomalies in the isotopic composition of Mo have been reported in several iron meteorites.29,30 Additionally, some irons also contain Ru isotope anomalies.31 In the case of the iron peak elements, anomalies in the neutron-rich isotopes (e.g., 48Ca, 50Ti, 54Cr, 62Ni, 64Ni, 66Zn) have been identified in CAIs20,32-36 but have thus far been noted only for 54Cr in bulk samples of undifferentiated and differentiated meteorites.37,38 Confirmation of the presence of such effects, (29) Dauphas, N.; Marty, B.; Reisberg, L. Astrophys. J. 2002, 565, 640-644. (30) Chen, J. H.; Papanastassiou, D. A.; Wasserburg, G. J.; Ngo, H. H. Lunar Planet Sci. 2004, 35, no. 1431. (31) Chen, J. H.; Papanastassiou, D. A.; Wasserburg, G. J. Lunar Planet Sci. 2003, 34, no. 1789. (32) Lee, T.; Papanastassiou, D. A.; Wasserburg, G. J. Astrophys. J. 1978, 220, L21-L25. (33) Jungck, M. H. A.; Shimamura, T.; Lugmair, G. W. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 1984, 48, 2651-2658. (34) Niederer, F. R.; Papanastassiou, D. A.; Wasserburg, G. J. Astrophys. J. 1980, 240, L73-L77. (35) Niemeyer, S.; Lugmair, G. W. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 1981, 53, 211-225. (36) Loss, R. D.; Lugmair, G. W.; Davis, A. M.; MacPherson, G. J. Astrophys. J. 1994, 436, L193-L196. (37) Trinquier, A.; Birck, J. L.; Allègre, C. J. Lunar Planet Sci. 2005, 36, no. 1259. Analytical Chemistry, Vol. 78, No. 24, December 15, 2006 8481 particularly in meteorites from differentiated parent bodies, has important implications for the efficiency and spatial scale of mixing and homogenization in the solar nebula. Our analyses show no clearly detectable non-mass-dependent anomalies in the 61Ni/58Ni and 64Ni/58Ni ratios in the samples analyzed here (Table 2; Figures S-3 and S-4). Possible exceptions may be metal from the Semarkona chondrite and the Canyon Diablo iron meteorite, which have slightly positive 61 and 64 values, respectively. However, in these two cases, the anomalies are only marginally outside of the 2σ external precision and are not considered unambiguous. If there had been systematic anomalies in the neutron-rich isotopes of Ni (62Ni and 64Ni), our normalization to the 62Ni/58Ni ratio would have resulted in systematic anomalies in the ,60 61, and 64 values, which we do not observe. A preliminary report by Bizzarro et al.39 suggests the presence of anomalies in 62Ni in iron meteorites; however, the reported effects are smaller than our analytical precision. Therefore, at the current level of our analytical precision, we are unable to unambiguously resolve any anomalies of nucleosynthetic origin in the Ni isotopic compositions of meteoritic metal samples. If, as is suggested by the data for CAIs,20 Ni isotopic heterogeneity existed in the solar nebula, our data indicate that Ni was homogenized (at least to the level of the analytical precision demonstrated here) sometime after the formation of these CAIs but before the formation of meteoritic metal in the parent bodies of both undifferentiated (i.e., chondrites) and differentiated (i.e., iron meteorites and pallasites) meteorites. Alternatively, the homogeneous isotopic composition of meteoritic metal relative to CAIs could represent spatial rather than temporal differences in the solar nebula, and the 60Fe-60Ni chronometer does not necessarily constrain the timing of a homogenization event, if it, in fact, took place. Furthermore, the formation of meteoritic metal may have acted to homogenize the precursor material to the degree that anomalies were not preserved at the parent-body scale sampled by the metal. In the following discussions, it will be assumed that any resolvable 60 deviations in meteoritic metal are solely the result of the decay of 60Fe. This does not preclude the possibility of the presence of nucleosynthetic anomalies in Ni isotopes that may be unresolved with our current analytical precision. Effects in 60Ni/58Ni Ratios from 60Fe Decay in Meteoritic Metal: The Expectation. Figure 6 shows the predicted values of 60 in meteoritic metal if one assumes that the Fe/Ni fractionation event that resulted in the formation of this metal occurred within the first ∼6 My of solar system history. Different symbols depict metals with different 56Fe/58Ni ratios, and the curves represent the values of 60 that would be measured today in samples that formed from a chondritic reservoir at the time specified on the x axis, where 0 My marks the beginning of the solar system. For these calculations, the solar system initial 60Fe/56Fe ratio was assumed to be 1.0 × 10-6,7-8 which corresponds to an initial 60 ) -0.63. Moving from 0 to 6 My along the x axis, the 60Fe/56Fe ratio decreases, and the 60 value increases in the reservoir from which the metal forms. If the solar system initial 60Fe/56Fe ratio was as high as 4.4 × 10-6,40 the calculated 60 trajectories in Figure 6 would be shifted toward more negative (38) Shukolyukov, A.; Lugmair, G. W.; Bogdanovski, O. Lunar Planet. Sci. 2003, 34, no. 1279. (39) Bizzarro, M.; Ulfbeck, D.; Thrane, K. Lunar Planet. Sci. 2006, 37, no. 2020. 8482 Analytical Chemistry, Vol. 78, No. 24, December 15, 2006 Figure 6. Predicted values of 60 in meteoritic metal that formed in the early solar system. Formation from a chondritic reservoir with a solar system initial 60Fe/56Fe ) 1.0 × 10-6 and 60 ) -0.63 is assumed. The time of formation is given on the x axis, where a time of 0 My corresponds to the beginning of the solar system. The 60 values expected for metals with the following 56Fe/58Ni ratios are shown by the various curves: 5 (squares), 10 (circles), 15 (triangles), and 20 (diamonds). The external precision (2σ) for our 60 measurements is shown by the two dashed lines ((0.15 ). values. As shown in Figure 6, deficits in 60 are expected in early formed objects with subchondritic 56Fe/58Ni ratios. Metals in iron meteorites,41 pallasites,42 and chondrites43,44 typically have Ni concentrations g5.5 wt %, with the maximum 56Fe/58Ni ratio in these samples being nearly identical to the chondritic value (24.4).45 Therefore, Figure 6 demonstrates that if 60Fe was live in the early solar system, early formed meteoritic metal with a subchondritic 56Fe/58Ni ratio is expected to record deficits in 60 unless it underwent subsequent equilibration. Meteoritic metal is not expected to show excesses in 60, regardless of its time of formation. As discussed in more detail in the following sections, our data and those of Quitté et al.21 are fully consistent with this expectation. Effects in 60Ni/58Ni Ratios from 60Fe Decay in Meteoritic Metal: The Observation. Figure 7 shows the 60 values measured in meteoritic metal. As is evident from Table 2 and Figure 7, no resolvable excesses in 60 were detected. In particular, no such excesses were observed in the metal phase of Casas Grandes, Canyon Diablo, and Forest Vale, contrary to a previous report.9 Furthermore, an 60 value of ≈ +1 had been previously measured in Toluca metal;46 therefore, two separate aliquots from a single digestion were obtained from Lyon for interlaboratory comparison. One aliquot had been chemically processed in Lyon for Ni separation, and the other was unprocessed; the latter was processed at the Field Museum, and both aliquots were analyzed. Neither aliquot showed excesses in 60, and the datum for Toluca in Figure 7 represents the mean of all the measurements made on both aliquots. An independent study of the Ni isotopic (40) Quitté, G.; Latkoczy, C.; Halliday, A. N.; Schönbächler, M; Günther D. Lunar Planet Sci. 2005, 36, no. 1827. (41) Scott, E. R. D. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1972, 36, 1205-1236. (42) Wasson, J. T.; Choi, B.-G. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2003, 67, 3079-3096. (43) Rambaldi, E. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 1976, 31, 224-238. (44) Rambaldi, E. R. Earth Planet Sci. Lett. 1977, 36, 347-358. (45) Anders, E.; Grevesse, N. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1989, 53, 197-214. (46) Moynier, F. Personal communication; 2005, Ecole Normale Supérieure de Lyon. Figure 7. 60 for metal from nonmagmatic irons (half-filled circles), magmatic irons (open circles), pallasites (triangles), and chondrites (half-filled squares). Plotted errors are 2σm; the external precision (2σ) is shown by the two dashed lines ((0.15 ). composition of the metal from 33 iron meteorites (including Canyon Diablo and Toluca) found no resolvable non-massdependent effects in the 60Ni/58Ni ratio in these samples.21 Bizzarro et al.39 recently reported that the metal from magmatic and nonmagmatic iron meteorites is characterized by deficits in 60 ranging from -0.11 ( 0.07 to -0.28 ( 0.11 (indistinguishable within their analytical uncertainties). Our analyses of iron meteorites yield 60 values that are mostly zero within 2σm uncertainties (some as small as (0.06 ), and there is no clear indication of a uniform deficit in 60 of ≈-0.2. Nevertheless, it is possible that some may record slightly negative 60 values that are not resolvable given our current external precision on 60 of (0.15. In addition, there is one iron meteorite sample (Hoba) that does appear to have a resolvable deficit in 60 (Table 2; Figure 7). No resolvable effects in 60 were detected in the metal from pallasites. However, clearly resolvable deficits in 60 were measured in the metal from the least equilibrated chondrites belonging to the LL3.0 (Semarkona), CR (Renazzo), and CBa (Gujba) classes, whereas the metal from the more equilibrated chondrites belonging to the LL3.1 (Bishunpur), H4 (Forest Vale), and EH4 (Indarch) classes are characterized by normal (i.e., terrestrial) 60 values. Resolvable E60 Deficits in Primitive Chondrite Metals: Implications for the Initial 60Fe/56Fe in the Early Solar System. As discussed above, resolvable deficits in 60 were measured in the metal from the least equilibrated chondrites studied (Semarkona, Renazzo, and Gujba). These 60 deficits indicate that the fractionation events that established the Fe/Ni ratios in these metals occurred while 60Fe was extant in the early solar system. Assuming a chondritic initial source reservoir (i.e., characterized by a normal 60 value and a 56Fe/58Ni ratio of 24.445), the 60Fe/56Fe ratios at the time of these fractionation events may be estimated on the basis of a single-stage model calculation using the measured 60 deficits (considered with the 3σm error or the 2σ external precision, whichever is larger) and the Fe/Ni ratios in these metals. Such a calculation yields 60Fe/56Fe ratios of (1.0 ( 0.6) × 10-6, (3.4 ( 2.8) × 10-6, and (3.5 ( 3.0) × 10-6 for metal samples from Semarkona, Renazzo, and Gujba, respectively. Within uncertainties, these values are indistinguishable and yield a weighted mean of (1.2 ( 0.6) × 10-6 for the 60Fe/56Fe ratio at the time of the Fe/Ni fractionation event for metal in these Figure 8. A plot of 60 vs 56Fe/58Ni for metal from magmatic irons and pallasites. The plotted errors are either the 2σm errors or the 2σ external precision ((0.15 ), whichever is larger. The chondritic point (square) is shown for reference only. The slope of the best-fit line corresponds to an 56Fe/60Fe ratio of (4.6 ( 3.3) × 10-7. Symbols are the same as in Figure 6. Note that the error bars on the 56Fe/58Ni ratios are smaller than the symbols. primitive chondrite samples. Assuming that the 60 deficits in metal from Semarkona, Renazzo, and Gujba are solely from the decay of 60Fe, this value must be treated strictly as a lower limit on the initial 60Fe/56Fe ratio for the solar system. The components, including metal grains, in the least equilibrated primitive chondrites are among the most pristine materials in the early solar system and record nebular processes.22,47 Although this is almost certainly the case for Semarkona and Renazzo, it may be argued that the Fe/Ni ratio in the Gujba metal was established ∼5 My or so after the formation of the refractory calcium aluminum-rich inclusions (CAIs, believed to be among the first solids to form in the solar nebula),48 during an impact event that formed the silicate chondrules in this meteorite.49 However, the fact that the measured 60 deficits (and Fe/Ni ratios) in Gujba metal are similar to those in Renazzo metal may be an indicator that the Fe/Ni ratio in the former was inherited from precursor material whose Fe/ Ni ratio was established earlier in the solar nebula. If, indeed, the Fe/Ni ratios in these metals were established early in the history of the solar nebula (i.e., almost contemporaneously with CAI formation), the value of (1.2 ( 0.6) × 10-6 is likely to be close to the solar system initial 60Fe/56Fe ratio. This value falls in the range of those proposed for the solar system initial 60Fe/56Fe by other recent studies.7-8 Moreover, as also suggested by these studies, this inferred initial 60Fe/56Fe ratio of ∼1 × 10-6 provides support for the hypothesis that this radionuclide was injected into the solar nebula from a stellar source (most likely a Type II supernova) and is likely to have served as an important heat source for planetesimal differentiation. Nickel Isotope Systematics in Magmatic Iron Meteorites and Pallasites: Implications for Timing of Fe/Ni Fractionation on Differentiated Parent Bodies. Figure 8 shows a plot of 60 vs 56Fe/58Ni for metal from differentiated parent bodies (i.e., magmatic iron meteorites and pallasites). The slope of the best(47) Krot, A. N.; Meibom, A.; Weisberg, M. K.; Keil, K. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 2002, 37, 1451-1490. (48) Amelin, Y.; Krot, A. N.; Hutcheon, I. D.; Ulyanov, A. A. Science 2002, 297, 1678-1683. (49) Krot, A. N.; Amelin, Y.; Cassen, P.; Meibom, A. Nature 2005, 436, 989992. Analytical Chemistry, Vol. 78, No. 24, December 15, 2006 8483 fit line through these data yields an initial 60Fe/56Fe ratio of (4.6 ( 3.3) × 10-7 and does not support the previously reported10 value of (3.0 ( 0.2) × 10-6 that is based on metal from iron meteorites, pallasites, chondrites, and mesosiderites. There are three main, sequential processes that affected the compositions of planetary cores: condensation and accretion of the parent body in the nebula, metal-silicate separation on the parent body during core formation, and crystallization of the metallic core.41 The chemical differences between planetary cores (i.e., represented by different groups of the magmatic irons) are attributed to a combination of condensation, accretion, and core formation processes, whereas variations among different samples from the same group are attributed to core crystallization. All of these processes likely contributed to the full range in Fe/Ni ratios shown in Figure 8. However, the bulk Fe/Ni compositions of planetary cores were probably established during metal-silicate separation on their parent bodies. During this process, Fe may partition into silicates, sulfides, metal, or all three, whereas Ni partitions strongly into the metal phase.41 The final Fe/Ni ratio of a particular sample within a magmatic iron meteorite group will depend on its position in the crystallization sequence, since the solid metal becomes progressively enriched in Ni as crystallization proceeds. Thus, the Fe/Ni compositions of magmatic iron meteorites and pallasites predominantly result from parent body, rather than nebular, processes. Furthermore, the total variation in Fe/Ni ratios within many magmatic groups is ∼20%,41 whereas the Fe/Ni ratios shown in Figure 8 vary by a factor of 3.3. As such, most of this variation is controlled by differences among groups, rather than within groups. Therefore, the overall variation in Fe/Ni shown in Figure 8 is likely controlled primarily by the Fe/Ni fractionation during core formation on different parent bodies. The slope of the Fe-Ni isochron shown in Figure 8 is meaningful only if the fractionation events that established most of the variation in Fe/Ni ratios occurred approximately contem- 8484 Analytical Chemistry, Vol. 78, No. 24, December 15, 2006 poraneously (at least within the precision of the 60Fe/60Ni chronometer). If this is so, and if one assumes a solar system initial 60Fe/56Fe ratio of ∼1 × 10-6 (see discussion in the previous section), the Fe/Ni fractionation recorded in metal from the +2.7 magmatic iron and pallasite meteorites occurred at 1.7-1.2 My after CAI formation. Previous studies of 182Hf-182W systematics in the iron meteorites indicate that metal-silicate segregation on the parent bodies of the various magmatic iron meteorite groups occurred within a narrow time interval, at most within a few million years of CAI formation.15-17 The 60Fe-60Ni systematics in the magmatic iron and pallasite meteorites studied here (including the timing of the major Fe/Ni fractionation events implied by the isochron in Figure 8) are consistent with these 182Hf-182W systematics. ACKNOWLEDGMENT We thank Laure Dussubieux for assistance with the quadrupole ICPMS analyses, F. Moynier and F. Albarède (Ecole Normale Supérieure de Lyon) for providing aliquots from their solutions of Toluca, the Smithsonian Institution for providing the sample of Semarkona (USNM 1805), and helpful comments by two anonymous reviewers. This work was supported in part by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration through grants to MW, RNC, and AMD. SUPPORTING INFORMATION AVAILABLE Figures S-1-S-4 (two pages) are available as Supporting Information. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org. Received for review July 16, 2006. Accepted September 28, 2006. AC061285M S-1 Authors and Affliations David L. Cook1,2,3, Meenakshi Wadhwa1,2,3, Philip E. Janney3, Nicolas Dauphas1,2,4, Robert N. Clayton1,2,4, and Andrew M. Davis1,2,4 1 Department of the Geophysical Sciences, The University of Chicago, 5734 S. Ellis Ave., Chicago, IL, 60637. 2Chicago Center for Cosmochemistry, 5640 S. Ellis Ave., Chicago, IL, 60637. 3Department of Geology, The Field Museum, 1400 S. Lake Shore Dr., Chicago, IL, 60605. 4Enrico Fermi Institute, 5640 S. Ellis Ave., Chicago, IL 60637. Title High Precision Measurements of Non-Mass Dependent Effects in Nickel Isotopes in Meteoritic Metal via Multi-Collector ICPMS Contents Figure S-1. Figure S-2. Figure S-3. Figure S-4. 4 3 2 1 ε 61 0 -1 -2 -3 -4 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 analysis number Figure S-1. ε61 values for repeated analyses of an Aesar Ni solution over the course of a 24month period. Each datum represents the mean of 5 repeat measurements performed during a single analysis session. The individual error bars are 2σm errors, based on the 5 repeat measurements for each datum. The external precision is the standard deviation (2σ) based on all of the data plotted here, and is shown by the two dashed lines (± 0.85 ε). 6 4 2 ε 64 0 -2 -4 -6 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 analysis number Figure S-2. ε64 values for repeated analyses of an Aesar Ni solution over the course of a 24month period. Each datum represents the mean of 5 repeat measurements performed during a single analysis session. The individual error bars are 2σm errors, based on the 5 repeat measurements for each datum. The external precision is the standard deviation (2σ) based on all of the data plotted here, and is shown by the two dashed lines (± 1.5 ε). -4 -3 -2 -1 0 1 2 3 4 -4 -3 -2 -1 0 1 61 2 3 4 ε Figure S-3. ε61 for meteoritic metal. Symbols and samples same as Figure 7. Plotted errors are 2σm; the external precision (2σ) is shown by the two dashed lines (± 0.85 ε). -6 -4 -2 0 2 4 6 -6 -4 -2 0 64 2 4 6 ε Figure S-4. ε64 for meteoritic metal. Symbols and samples same as Figure 7. Plotted errors are 2σm; the external precision (2σ) is shown by the two dashed lines (± 1.5 ε).