Poems of Billy Collins impress critic

advertisement

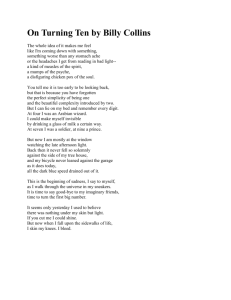

Index 10 THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 14, 2013 What you’ll need: - quart mason jar ($1.87 from Wal-Mart) - patterned masking tape ($2.88 each from Wal-Mart) - decoupage ($4.99 from Wal-Mart) - paint brush - scissors - markers By Emily Wichmer MASON JAR VASE STEP ONE Tot a Cos l t : $9. 74 STEP TWO FINAL STEP Wash the mason jar and remove any stickers. Let dry. Starting at the base, wrap tape around the jar until it is completely covered. STEP THREE STEP FOUR Add a ribbon or bow if you’d like, fill the vase with water, and display your favorite flowers. Use markers to decorate and embellish the tape. Cover the jar with an even coat of decoupage and let dry. Next week’s Crafty Dog: Crayon Ornament Poems of Billy Collins impress critic We might be tempted to say there’s not much to understand about Billy Collins. Upon a quick reading, one might call his style “conversational” or “plain-spoken.” He often writes about places, people and experiences readers tend to know. He keeps unfamiliar words to a minimum. His poems seem artless, with a lack of recognizable meter or rhyme and arbitrary length of stanzas — perhaps more accurately called “line clusters.” And for another thing, he’s actually funny. This isn’t poetry. This is comfort food. Au contraire, Billy Collins knows his poetic tools. What seems so artless to casual readers is that he doesn’t use these tools to the point that he is incomprehensible, as many poets of our time like to do. What’s so poetic about his poems? I might point to the line breaks. He loves to undercut his own lines, a poetic device called “bathos.” For example, “The Literary Life” begins, “I woke up this morning, / as the blues singers like to boast...” The second line is an ironic addition to the earnest first line. Much of his humor comes from bathos and, on a grander scale, the way he moves by free association from one subject to a completely different one. For example, in “To My Favorite 17-Year-Old High School Girl,” the narrator begins talking to this girl, but then starts comparing her to significant historical figures as adolescents, but by the end, we find him admitting, “By the way, I lied about Schubert doing the dishes, / but that doesn’t mean he never helped out around the house.” These little poems move quite a bit from A to B. Collins’ poems are particularly fun when they mock conventions. In “Tension,” he uses “suddenly” — which is a no-no, as the epigraph before the poem states — again and again while describing a normal domestic scene. He uses bathos here too — “ ... suddenly you announced you were leaving / to pick up a few things at the market ... ” “Adage” piles up a number of clichés while talking of love. And then there’s “Looking for a Friend in a Crowd of Arriving Passengers: A Sonnet,” which mocks the popular 14-line form by repeating “Not John Whalen” for 13 lines and then — suddenly — “John Whalen.” President of Truman State University A few of President Paino's favorite songs: “You and I” by Wilco “Someday, Someway” by Marshall Crenshaw “A Hard Rain A-Gonna Fall” by Bob Dylan “This Must Be the Place (Naive Melody)” by Talking Heads To hear these and more of President Paino's favorite musical artists and top songs, tune in today (11/14) from 5 - 6 pm to Ph.D. Playlists! Right here on campus on KTRM - either listen live at 88.7 FM or online at http://tmn.truman.edu/ktrm/. Undergraduate degree: B.A. in History & Philosophy from Evangel University Graduate Degrees: J.D. from Indiana University M.A. in American Studies from Michigan State University Ph.D. in American Studies from Michigan State University Favorite musical genre: Rock, Traditional Roots and Alternative Favorite song: “Hurt” by Johnny Cash of the week BY MATT SLUDER “Aimless Love” by Billy Collins This is not to say Collins never is serious. “Horoscopes for the Dead,” an older poem, uses the innocuous newspaper horoscope to highlight a significant other’s absence. The tone changes drastically from the first poem, “Reader,” which pokes fun at poetry’s obscurity, to the last, “The Names.” Collins dedicates this poem to victims and survivors of 9/11. The narrator sees the victims’ last names everywhere throughout his day, moving through the alphabet like a morbid “Sesame Street” sketch. To me, the most chilling line in this poem is when he recognizes, as he often does, what’s not there — “let X stand, if it can, for the ones unfound.” It is the most poignant algebraic expression. If you think Collins is light reading, we must be talking about different poets.