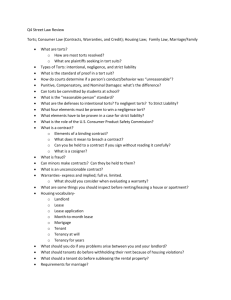

TORT LIABILITIES AND TORTS LAW: THE NEW FRONTIER OF

advertisement