doi:10.1016/j.cities.2008.04.003

Cities 25 (2008) 207–217

www.elsevier.com/locate/cities

Why city-region planning does not work

well in China: The case of Suzhou–

Wuxi–Changzhou

Xiaolong Luo

*

Nanjing Institute of Geography and Limnology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Nanjing 210008, PR China

Jianfa Shen

1

Department of Geography and Resource Management, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong

Received 16 April 2007; received in revised form 28 January 2008; accepted 20 April 2008

Available online 5 June 2008

In the age of globalization, the city-region is a form of spatial organization that promises to promote

inter-city cooperation and so enhance the competitiveness of the whole city-region. The notion was

well accepted in China recently and many local governments attempted to formulate city-region plans

for coordinated development. City-region planning thus becomes a new form of Chinese spatial planning, led often by a higher-level government. This study attempts to analyze the processes of cityregion planning and implementation, and the behavior of provincial and city governments, by a case

study of Suzhou–Wuxi–Changzhou city-region planning. Despite a strong hierarchical administrative

system, it is found that the city-region planning did not work well. Lack of actor interaction and

information exchange during the top-down planning process, the difficulties in specifying detailed

planning contents, and a lack of good planning mechanisms are major factors in unsuccessful planning implementation, making powerful city governments prone to inter-city competition even within

the same region. The findings echo the recent experiences in Western countries that emphasize the

needs of interaction, negotiation and consensus building in the planning process. A more powerful

regional institution in charge of city-region planning and implementation is needed for sustainable

development of city-regions in China.

Ó 2008 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: City-region, Suzhou–Wuxi–Changzhou city-region planning, China

Introduction

ning are often conceived as wise policy choices for cities

to build competitiveness in the UK and other Western

European countries (for example, Cooke et al., 2004;

Heeg et al., 2003; Wannop, 1995).

Recent developments show that cities in China have

seen similar changes. The term city-region (Dushi Quan)

has also become a catchword in academics and government documents. Many cities are making their city-region

plans in order to enhance their competitiveness and

facilitate regionalization. However, such planning often

cannot achieve its expected goals. This study attempts

to unveil the reasons that can cause the failure of such

planning, using the case of Suzhou–Wuxi–Changzhou

City-region Planning (SWC planning). This paper is a

City-regions have become the motors of the global economy in the age of globalization. Facing cross-border competitive pressure, city-regions are engaged actively in

institution-building and policy making in an effort to turn

globalization as far as possible to their benefit (Scott et al.,

2001). But economic coordination in such regions remains

a great challenge. Urban networking and regional plan-

*

Corresponding author. Tel.: +86 25 86882132; e-mails: xluo@niglas.

ac.cn, jianfa@cuhk.edu.hk

1

Tel.: +852 26096469.

0264-2751/$ - see front matter Ó 2008 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

207

Why city-region planning does not work well in China the case of Suzhou–Wuxi–Changzhou: X Luo and J Shen

preliminary enquiry on the practice of city-region planning and development in China.

This paper is organized as follows. The following section considers inter-city competition and city-region planning in post-reform China to provide a background for

this study. The third section introduces the SWC planning

as a background. The process of SWC planning is analyzed in the fourth section. In the fifth section, the implementation of SWC planning is assessed. Redefinition of

city-regions by cities in SWC region is addressed in the

sixth section to illustrate inter-city competition. Some

conclusions are reached in the final section.

Inter-city competition and city-region planning in

post-reform China

The transition from state socialism to market economy

has posed great challenges to cities in China. A local

developmental state has emerged. Cities are keen on inter-city competition instead of cooperation (Shen, 2007;

Wu, 2000; Zhang, 2002). In the competition to attract foreign investors to their own cities, the local states are keen

to embark on place promotion, prestige projects and mega

events (Wu, 2000). They also offer tax concessions and

cheap land for investors (Xu and Yeh, 2005; Zhu, 1999,

p. 541). Some forms of intervention, regulation and coordination are thus essential as leaders of Chinese cities lack

financial discipline and public accountability (Xu and

Yeh, 2005). Indeed, regional coordination has been promoted by the Chinese government for a long time, aiming

for balanced spatial development and poverty alleviation.

Urban system planning was a coordinative instrument designed to organize cities into hierarchies within metropolitan areas, with different functions to overcome excessive

competition and duplication of infrastructure.

In recent years, many city governments have attempted

to build city-regions to enhance competitiveness (Gao,

2004; Qian and Xie, 2004; Zhang, 2003). City-region planning is becoming a new initiative in Chinese spatial planning. Over 15 cities have formulated city-region plans in

the whole country.2 City-region planning aims to coordinate several political entities, i.e., administrative areas,

within the same region (Wang, 2003). This coordinative

feature makes it different from the traditional urban and

regional planning in China that emphasizes both control

and development within the hierarchical administrative

system, such as urban master planning and urban system

planning (Ng and Tang, 2004a; Yeh and Wu, 1998). Indeed, urban master planning is made generally for the

core urban area of a single city while urban system planning and regional planning have been rare and ineffective

in the past. Thus, the new city-region planning is considered as a new mode of urban and regional governance

by some Chinese researchers (Li, 2004).

To understand city-region planning in China, it is also

necessary to examine the role of provincial governments

in the formulation and implementation of city-region

planning, as provincial governments are the key player

2

http://www.sina.com.cn, 8 July, 2004.

208

of city-region planning in practice. Generally speaking,

in China, a city-region is part of a province and consists

of several prefecture-level cities that may administer some

counties/county-level cities. In the reform period, city

governments acquired great administrative and economic

power due to decentralization from central and provincial

governments (Shen, 2007). Prefecture-level cities are relatively independent administrative units. There is more

competition than cooperation among these prefecture-level cities, especially those more open and developed cities

along the coast. To coordinate the development of prefecture-level cities, most provincial governments, as the highest level of local governments, often function as

coordinators to facilitate city-region development, by

making and implementing city-region plans. A city-region

plan is formulated by a provincial government and approved by itself, instead of a higher-level government.

As a new initiative of Chinese spatial planning, the mechanism for city-region planning is not well established. The

provincial government only has limited influence on city

governments, due to the rising power of local governments in China. Without thorough consultation and horizontal exchange and negotiation, the city-region planning

is bound to face problems in the stages of formulation and

implementation, as will be shown by the SWC case in this

paper. In some cases, city-region plans are driven by prefecture-level cities such as Harbin and Nanchang, as provincial capitals. In these cases, the city-region plan may be

implemented more smoothly. But there may be conflicts

between prefecture-level cities and their surrounding

areas.

A fewer studies have focused on the transformation of

urban and regional planning (Leaf, 1998; Ng and Tang,

1999,2004a,2004b; Ng and Xu, 2000; Xu and Ng, 1998;

Yeh and Wu, 1998; Zhang, 2002). Many scholars argued

that the government plays a dominant role in urban and region planning and the planning is not effective in development control in China (Ng and Xu, 2000; Xu and Ng, 1998;

Zhang, 2000). According to Ng and Xu (2000), ineffective

planning is caused by the absence of well-established

planning institutions, the arbitrary intervention of higherranking government officials, and widespread illegal land

transactions and land use (Wei and Li, 2002; Zhang,

2000; Zhu, 2004). Worse still, local officials often have a

short term of office but have the absolute power to commit

to large projects without a well-articulated decision-making mechanism. Cities often have no urban planning committee or advisory committee. Urban development

strategies and construction plans may be changed suddenly

due to a change in the top leadership of a city (Zhu, 1999).

There is one exception. Abramson et al. (2002) argued that

Quanzhou’s planning is relatively successful due to the

absence of state investment, the unusual high degree of

participation by local communities and the need for historical preservation (the government acting as preserver).

Previous studies reviewed above provide useful insights

for understanding urban and regional planning in China.

However, there are still some problems in the existing

literature. First, the analysis of the processes of planning

formulation and implementation is inadequate. We are

still unsure if planning formulation and implementation

will affect the effectiveness of planning. Second, local

Why city-region planning does not work well in China the case of Suzhou–Wuxi–Changzhou: X Luo and J Shen

governments have their own interests in urban development. They adopt and pursue different policies and strategies of urban and economic development. Therefore, to

evaluate planning effectiveness, it is necessary to examine

the behaviors of various governments and their interaction

in the planning process. Finally, as a new kind of planning

in the Chinese urban and regional planning system, no

study has been made on city-region planning in China.

SWC planning is selected for a detailed case study in

this paper. The SWC plan was formulated in 2002 and

was the first city-region plan approved by the Chinese

government. SWC planning has been highly praised by

the Ministry of Construction, not only as a model of

city-region planning, but also a solution for excessive urban competition. However, as a new and experimental

instrument by governments, city-region planning has inevitably encountered various problems in the process of plan

making and implementation. Its implementation has not

been effective since the completion of the plan. In this

study, we will trace the planning process and examine

stakeholder interaction. Through these two lenses, this

paper attempts to examine why city-region planning does

not work well in China.

The SWC planning: the region and planning

objectives

The SWC city-region consists of three prefecture-level

cities of Jiangsu province, Suzhou, Wuxi and Changzhou,

which is the core area of Yangtze River Delta (YRD)

Region (Figure 1). The SWC region can be seen as a

new regional entity created by the Jiangsu provincial

government. The region had a population of 12.63 million in an area of 18,011 km2 in 2002. Although the region accounted for only 17.55% and 17.00% of the

total area and population in Jiangsu, respectively, its

GDP (RMB 690.06 billion) accounted for 44.48% of

the provincial total in 2002 (JSSB, 2003). The SWC

city-region is one of the most urbanized regions in China. There were 3 prefecture-level cities consisting of 9

county-level cities and 19 urban districts in 2002. With

the same administrative rank and power, main cities

and county-level cities engaged in intense competition

for foreign direct investment (FDI) and infrastructure

projects such as railways and airports. Local governments implemented various economic and administrative

policies to protect local interests. Some authors have argued that administrative boundaries prevent the free

movement of production factors such as capital, labor

and technology (Liu, 1996; Zhang et al., 2002). Such

competition has caused many acute problems, such as

the duplication of industrial structure, urban sprawl and

environment pollution (JSCC and JSURPI, 2002). In

addition, the SWC city-region can be regarded as a polycentric city-region (PCR) which often faces fierce urban

competition (Kloosterman and Lambregts, 2001).

In order to alleviate the serious problems of urban competition mentioned previously, the provincial government

of Jiangsu initiated SWC Planning to coordinate the

development of three cities in the region in 2001, when

Jiangsu province began to implement its urban system

plan. The provincial Construction Commission consigned

the planning task to the Jiangsu Urban and Rural Planning Institute and the Urban Planning Institute of Nanjing

University to produce the plan jointly. The SWC Plan can

be viewed as a blueprint for cooperation initiated by the

higher-level provincial government to coordinate development among three cities. In this sense, it is very similar

to ‘‘the vertical policy coordination’’ in Germany’s regional planning (Arndt et al., 2000). Officially, four major

objectives of SWC planning are stipulated (JSCC and

JSURPI, 2002).

The first objective is to make use of the dominant role

of the SWC city-region for regional economic development. The SWC region should become an engine of

development in the province, stimulating the development of northern and middle regions of Jiangsu.

The second objective is to alleviate problems of serious

urban competition and to enhance urban and regional

competitiveness.

Figure 1 Location of Suzhou, Wuxi and Changzhou and other major cities.

209

Why city-region planning does not work well in China the case of Suzhou–Wuxi–Changzhou: X Luo and J Shen

The third objective is to improve the relationship

between the SWC region and Shanghai. It is undeniable that the development of the SWC region benefits

greatly from its proximity to Shanghai, an emerging

global city (Shi and Hamnett, 2002). However, in

recent years, the Shanghai Government implemented

the 173 Project, aiming to develop an Experimental

Industrial Zone of 173 km2 in its suburban areas. Many

preferential policies were offered to manufacturing

investors. This initiative enhanced Shanghai’s competitiveness in manufacturing industry, competing against

the SWC region for investment. Thus adjusting the

relationship between Shanghai and the SWC region is

an urgent issue.

The fourth objective is to enhance regional competitiveness to face the challenges of economic globalization and China’s WTO accession.

The process of SWC planning

SWC planning was a comprehensive process covering

industry, infrastructure development, spatial planning,

environment protection and more. It was initiated by

the provincial government and was conducted by planning

institutes with passive involvement of the governments,

officials and planners in three cities. Thus, it was formulated and implemented in a top-down manner, reflecting

the provincial government’s intention of cooperation

and coordination. During the planning process, planning

institutes only functioned as bridges among the governments of the three cities and the province. The top leaders

of provincial and city governments were influential in the

formulation of planning and development strategies. Planners were subordinated to the bureaucratic machine in

China and could not play their professional role well in

development control (as observed by Yeh and Wu, 1998).

On the other hand, there was little information exchange and interaction among various governments, preventing cities from reaching consensus and building up

mutual trust. In fact, formulation of a coordinative plan

in a top-down manner in the SWC planning process triggered many disputes, such as with regard to infrastructure

development and land-use planning, as no city government had an interest in talking to fellow cities. They were

interested only in bargaining with the provincial government in the top-down planning process. They tended to

maximize their own interests and simply ignored the interest of others. Typical cases include the location of proposed airports and bridges across the Yangtze River.

The following will examine the case of new airport

location.

The SWC region has been served by the Shanghai Hongqiao Airport for many years, but international flight services were re-located from Hongqiao airport to the new

Pudong airport in recent years. This change considerably

increased the distance from the SWC region to the international airport and negatively affected SWC’s accessibility in international air transportation of goods and

passengers. In order to solve this problem, the provincial

government decided to construct a new airport for southern Jiangsu, as the three cities had a small airport each

210

with limited capacity. This was a key project in SWC planning. Therefore, fighting for hosting the new airport came

to a climax in the planning process. Each city had its own

reasons to compete with others for the proposed airport:

‘‘Suzhou: Most FDI and foreign investors are concentrated

in Suzhou. The move of international airport in Shanghai

has had more negative effects on Suzhou’s export-oriented

economy than other fellow cities. The airport thus should be

located in Suzhou.

Wuxi: Situated in the middle of southern Jiangsu, Wuxi has

the locational advantage and thus the new airport will provide the best services for Suzhou and Changzhou. Moreover, Jiangyin Yangtze River Bridge in Wuxi will also

extend the service scope of the new airport to central and

even northern Jiangsu.

Changzhou: Currently, Changzhou has an airport with the

highest grade in SWC region. In order to avoid infrastructure duplication, the existing airport should be expanded

to become the new airport. In addition, Changzhou, as

the central city in the southern part of Jiangsu (da sunan,

the area on the south of Yangtze River in Jiangsu province),

has the locational advantage.’’3

The battle for the new airport forced the provincial government to create a compromise rather than a real solution. In the SWC plan, three existing airports would

remain in each city and the new airport, named Southern

Jiangsu Airport (Sunan jichang), was proposed to be located in Wuxi.4 However, Changzhou and Suzhou still

put forward their own airport proposals, subsequently

indicating that they did not agree with the plan at the very

beginning. This case supports the argument that active

lobbying by local governments can often change the decision of governments at upper levels in China5 (Walder,

1995). Perhaps, Changzhou and Suzhou also believed in

such chances in the decision-making process. Indeed, the

final decision on the opening of a new airport is in the

hands of Civil Aviation Administration of China rather

than the provincial government. Thus, the provincial government and even the SWC planners do not have the legal

power to enforce the development of a new airport in

Wuxi. There are three reasons for this to happen. First,

the SWC planning process on the location of airports does

not seek endorsement from the national authority in

charge of airport administration. Second, the provincial

government has weak administrative power and financial

capacity. Third, the local city governments have strong

administrative power and are financially responsible for

development projects such as airports. As a result,

upper-level intervention may not be successful. The best

solution is for the provincial or central governments to

cooperate airport development in the province and the

country without relying on local financial resources.

3

These reasons were raised by vice mayors of corresponding cities in

the final discussion conference in March 2002. One of authors attended

this conference.

4

China Interview 09060401.

5

According to the regulation of Chinese aviation industry, any new

airport proposals must be approved by the State Council, National Civil

Aviation Administration, and provincial governments. Due to some

reasons, Suzhou temporarily gave up its dream of airport later on.

Why city-region planning does not work well in China the case of Suzhou–Wuxi–Changzhou: X Luo and J Shen

Most interestingly, the lower level government did not

share the same interest with its prefecture-level government. Although three prefecture-level cities were competing for the new airport, all county-level cities under their

administration refused to build the proposed airport on

their land. The county-level cities did not like to allocate

land-use quotas for construction (jianshe yongdi zhibiao)

for the new airport.6 Indeed, almost all cities in the

YRD region had used up their land-use quotas for construction. It is clear that there are complicated relations

among cities at various levels, which call for close interactions for coordinative planning. But such interaction is

clearly lacking in SWC planning.

It should be pointed out that almost all infrastructure

projects proposed in the SWC plan were subjected to disputes among cities. The provincial government acknowledged that it could not force three cities to fully

implement the plan and the aim of planning was just to

provide a blueprint for cooperation, guiding cities toward

integration.7 Thus, the provincial government lacks the legal power to implement the planning. A coordinated plan

should pay more attention to the process of planning,

especially building trust and consensus among cities. Only

then would the direction for cooperation become clear.

But inadequate interaction for consensus building in

SWC planning inevitably leads to its failure in implementation; this will be examined in the following section.

Assessing the implementation of the SWC plan

The implementation of the SWC plan

In order to evaluate the performance of the plan implementation process after its approval in 2002, we interviewed the planning consignor (the Construction

Commission of Jiangsu Province), executors (three cities’

Urban Planning Bureaus) and planners (the Urban and

Rural Planning Institute of Jiangsu Province and the Urban Planning Institute of Nanjing University), respectively. The implementation of SWC plans will be

assessed according to five components of the plan including industry planning, spatial planning, environment protection planning, tourism planning and infrastructure

planning (Table 1). The first four components only document general macro-strategies and do not involve concrete projects or items. They can only be, and will be,

assessed generally. On the other hand, there are many

key projects in the infrastructure planning process that

can be traced one by one in the course of implementation.

The implementation of industry planning, spatial planning, environment protection planning and tourism planning is generally unsuccessful, as shown in Table 1.

Nothing has really been achieved, as there are no opera-

6

To overcome issues of farmland loss caused by rapid urban growth, the

Central Government of China controls the quantity of land-use conversion from agricultural land to land-use for construction tightly, by

introducing land-use quota for construction. The Central Government

allocates land-use quota for construction to provinces and then down to

cities and counties every year.

7

China Interview 10060401.

tional guidelines or solutions at the macro-level.8

Although such planning addresses important development

strategies and guidelines, the general statements in SWC

plans are difficult to operate and implement. Further

study is needed to seek how individual cities can actually

follow and respond to such general statements in cityregion planning through city-level regulation, and what

kind of mechanism can be adopted to ensure effective

implementation. In the existing planning system of China,

planning often stops when a plan is produced and no adequate mechanism is in place to implement or revise the

plan. In some cases, such as urban master planning, the

planning and approval processes are too long and often

lag behind the actual development on the ground.

The implementation of infrastructure planning can be

assessed directly; according to Table 1, it too does not

work well. There are 10 projects that were being changed

or debated, being suspended, were difficult to operate or

were cancelled (this out of 17 key projects (59%) investigated) in this research. The following outlines the situation and problems of these projects.

(i) Highway and railway projects: The projects of changing the route of national highway No. 312 and upgrading

Hu-Ning (Shanghai–Nanjing) railway in the SWC plan

are infeasible, and thus difficult to realize. Thus, upgrading national highway No. 312 and raising train speeds on

the Hu-Ning railway were adopted as alternatives. There

are also disagreements on the route of the river-side railway. Only the preparation for the planning of NantongShanghai railway has begun. The implementation failure

of most projects suggests that projects in a coordinative

planning cannot be easily implemented. Thus, such projects should be studied and discussed in detail before

being listed in the plan. Some ambitious projects that

are at preliminary stage of consideration should be considered and documented in background planning studies

only and should not be formally listed in the final plan.

(ii) Rail transit: According to the SWC plan, the provincial government has formulated a SWC rail transit plan. It

is impossible to ‘‘translate’’ these proposed projects into

concrete action in the near future as these projects rely

on local governments for implementation and input of

financial resources. Two rail transit projects listed in Table

1, Changshu-Wujiang rail transit and Changzhou-Wujin

rail transit were mentioned in the SWC plan. They were

considered as suspended as local governments have no

intention to implement these projects yet. Following

SWC planning, Wuxi city also prepared a JiangyinWuxi-Yixing Rail Transit Plan and only this Rail Transit

is under preparation.

(iii) Bridges: Suzhou-Nantong Yangtze River Bridge

and Changzhou-Taizhou Yangtze River Bridge have been

included in the province’s transportation planning as key

projects of the province. Suzhou-Nantong Yangtze River

Bridge is under construction.

(iv) Airport: One original objective of SWC planning

was to coordinate airport development in the region and

the province has attempted to focus on the development

of Changzhou airport, the highest level airport in the

8

China Interview 10060401 and China Interview 14060401.

211

Why city-region planning does not work well in China the case of Suzhou–Wuxi–Changzhou: X Luo and J Shen

Table 1 Implementation assessment of the SWC plan

Proposed projects

Industry planning

Spatial planning

Environment protection

Tourism planning

Infrastructure projects

Changing the route of national highway No. 312

Upgrading Hu-Ning railway

River-side railway

Nantong–Shanghai railway

SWC rail transit

Changshu–Wujiang rail transit

Jiangyin–Wuxi–Yixing rail transit

Changzhou–Wujin rail transit

Suzhou–Nantong Yangtze River Bridge

Changzhou–Taizhou Yangtze River Bridge

Changzhou Benniu Airport as the key airport (4D)

Upgrading Suzhou Guangfu Airport (4C)

Upgrading Wuxi Shoufang Airport (4C)

Sunan Airport

Wuxi logistics center

Regional natural gas supply

Regional water supply

Implemented/

implementing

Partly

implemented

Planning/

preparing

Changing/

debating

Suspended

Difficult to

operate

Cancelled

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

Source: The authors’ interviews. The interviewees are urban planners and local officials who are directly involved in the projects under investigation.

region at that time. But SWC planning failed to coordinate airport development. As stated in the plan (JSCC

and JSURPI, 2002),

‘‘(the province) gives the highest priority to the development of Changzhou Benniu Airport (4D-level, provincial

level airport); then to improve Wuxi Shoufang Airport

and Suzhou Guangfu Airport (4C-level, local level airport).

. . .. . . In order to meet the needs of local economic development and transport in the future, (the province) can construct a new airport in Wuxi’’.

Thus the three existing airports will be further expanded/

improved while a new airport will be built. It is clear that

the province is in a dilemma due to keen competition for

the new airport among three cities mentioned above. As argued by other scholars (Wei, 2001), higher-level governments in China can no longer control their subordinate

authorities in a command-and-control fashion due to the

growing power of local governments in the reform period.

The provincial government finds it difficult to force any city

to give up its own interests by order, such as closing the

existing airport. The conflict between collective interests

(the province and SWC region’s interests) and individual

cities’ interests cannot be easily solved by the provincial

government. After the coordination failed, surprisingly, a

proposal for a new airport, Sunan (Southern Jiangsu) Airport, was put forward by the provincial government. But

subsequent development of airports in the region did not

follow the trajectory set-up by the plan. In August 2003,

Wuxi Shoufang Airport began Phase II construction with

investment from Wuxi city government and the number

of flights increased to 21 a day, including flights to Hong

Kong and Macau by 22 August 2007, becoming the most

influential airport in the region. The Phase II expansion

212

was scheduled for completion by September 2007 and it

may replace the planned new Sunan Airport (Yao, 2007).

Thus, ‘‘giving the highest priority to the development of

Changzhou Benniu Airport’’ and the construction of Sunan new airport perhaps will never be implemented.

(v) Logistics center: In the SWC plan, the province proposed to establish Wuxi Logistics Center in southern

Jiangsu. Because it is just an idea of functional division

rather than a concrete project, its implementation relies

on local needs and the local government. In addition,

the need for such a logistics center should be decided by

the market, local economic development, and the strategy

of local government, rather than assignment by a high level government. Without thorough consultation with the

local government about the needs and possibility of the

logistics center, the project may not be realized.

(vi) Regional natural gas and regional water supply: The

provincial government has formulated thematic plans for

these on the basis of SWC Plans. According to interviews

in Jiangsu, each prefecture-level city can implement regional natural gas and water supply plans within its own jurisdiction. However, these projects face various handicaps at

the regional scale for two reasons. First, there is no trust

among three cities in the SWC region due to little information exchange and interaction among them. ‘‘Some cities worry that natural gas and water supplied to other

cities may be used ‘freely’ by other cities not following

the regulations’’9. Second, each city is keen to protect its

own economic interests. ‘‘Constructing one’s own waterworks and gasworks means that local governments can

make big profits with small amounts of capit al’’10.

Thus each city government is not willing to give up these

9

10

China Interview 14060401.

China Interview 15060401.

Why city-region planning does not work well in China the case of Suzhou–Wuxi–Changzhou: X Luo and J Shen

projects, which will result in infrastructure duplication. As

conflicts within one jurisdiction can be solved more easily

than those involving a couple of jurisdictions, some prefecture-level cities have successfully completed the projects of regional natural gas and water supply in their

own jurisdictions.11 Clearly, the government of a prefecture-level city can influence the county-level cities and districts more effectively than a provincial government over

the government of prefecture-level cities (Shen, 2007).

In conclusion, the performance of planning implementation is far from satisfactory. This is largely due to the

difficulties in specifying detailed contents of planning

and other reasons which will be analyzed in the next section in detail.

The reasons for unsuccessful plan implementation

In order to find out the reasons for ineffective plan

implementation, semi-structural interviews were conducted to collect additional information. Eleven interviewees were selected from the planning consignor (one

provincial official), planning institutes (two chief planners in two institutes), and planning executors (eight local officials in local planning bureaus and heads of local

planning institutes in three cities). They were asked to

indicate their views on city-region planning and the reasons for unsuccessful plan implementation. All interviewees are key figures involved in SWC planning. Thus,

the information obtained from these interviewees is

pertinent.

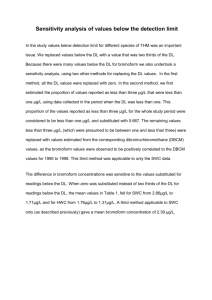

Regarding the role of city-region planning, almost all

interviewees believed that city-region planning was an

important instrument for building competitiveness and

sustainable development. However, they also acknowledged that while there is much competition in the SWC

region, cooperation is rare. They explained that there

are few complementarities in economic structure and

industry development among cities in the region. In the

long run, inter-city competition at a given spatial scale will

give way to cooperation in order to compete with other

scales effectively. For example, in the YRD region, various urban forums and cooperative initiatives have

emerged. However, in the SWC region, it will be a long

journey to form similar cooperative initiatives. Figure 2

presents three major reasons for unsuccessful planning

implementation mentioned by interviewees.

First, urban competition is the main cause of the implementation failure of SWC plans. There was keen competition in areas such as investment and infrastructure

projects, among three cities to be coordinated. As a polycentric city-region (Kloosterman and Lambregts, 2001),

competition was more serious in the region than other

city-regions in China. Thus, the prefecture-level city governments, who are the key players in implementing the

SWC planning, may not have much interest in cooperation. Most importantly, as SWC plans covered industry

development, functional division and infrastructure, it

was difficult for these cities to achieve consensus in so

many areas of cooperation. On the other hand, conflicts

11

China Interview 15060401 and China Interview 12060401.

between the provincial government and its subordinate

city governments also contributed to unsuccessful plan

implementation although they also had some common

interests. As mentioned in the previous discussion on

the planning process, the provincial government tried to

coordinate the development of subordinate cities by using

its policy-making power in an attempt to enhance the

competitiveness of SWC region. However, this also means

that the maximization of collective interest may be at the

cost of the interest of some individual cities. This inevitably spurred conflicts among governments at different

administrative levels.

To alleviate urban competition, the provincial government even exchanged local leaders between cities in

SWC region. For example, the Chinese Communist Party

(CCP) secretary of Wuxi was appointed as the CCP secretary of Suzhou; the mayor of Suzhou was appointed as the

CCP secretary of Wuxi. In China, the party secretaries are

generally the most influential top official (yibashou) at

each city in charge of nominating officials and policy-making while mayors are in charge of routine administrative

matters. By the above exchange of local officials in Suzhou and Wuxi, the provincial government attempted to

enhance the linkages between the two cities and coordinate two cities’ development. However, in practice, such

arrangement cannot alleviate urban competition at all.

Urban competition is still in place, because local economic development is regarded as the top priority of local

government. Furthermore, local officials’ possible promotion depends on economic performance of the city under

their leadership (Zhu, 2004).

Second, there was no coordinating mechanism among

cities for plan implementation. Although the provincial

government formulated the plan to coordinate the development of three cities, no measures were introduced

regarding plan implementation and administration. Thus

there was no mechanism to enforce the implementation

of the plan. The lack of good planning mechanisms also

caused serious conflicts among various plans. For example, the Development and Planning Commission, the

Land Use Bureau and the Urban Planning Bureau of

the province are in charge of regional planning, land-use

planning and urban planning, respectively. Each government department formulates their sector plans based on

their own interests, rarely considering other departments’

planning.

Thirdly, according to interviewees, many items specified

in the SWC plan were too general and difficult to materialize. Thus city governments could not fully ‘translate’

SWC plan into concrete actions. The unfeasibility of

SWC plan will result in the failure of plan implementation, let alone coordination and cooperation.

This case provides an important planning lesson on the

content of city-region planning. Whether a plan can be

successfully implemented or not depends on the content

of the plan. Generally speaking, a plan consists of

themes/projects at micro and macro levels that need to

be coordinated. General and unfeasible content that is difficult for implementation by local governments should be

avoided. Meanwhile, the content of a plan should also not

be too detailed, otherwise the plan will have little

flexibility.

213

Why city-region planning does not work well in China the case of Suzhou–Wuxi–Changzhou: X Luo and J Shen

D

Planning Consignor

C

Planning Institutions

B

Planning Executors

A

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

Reasons: A – Urban competition

B – Lack of coordinative mechanisms

C – Difficult to operate

D – Conflicts among governments at various levels

Figure 2 Reasons of unsuccessful plan implementation based on interviews.

The above analysis suggests that it is difficult to coordinate competitive projects in the planning process. Instead,

cities are inclined to form partnerships in those areas that

they share common interests, such as transportation

development. How to enhance city cooperation and coordination in competitive areas is the crux of the coordinative planning challenge.

In summary, urban competition, lack of necessary coordinating mechanisms, impractical planning content and

conflicts among governments at various levels are major

causes of ineffective implementation of SWC plan. In

terms of urban and regional governance, prefecture-level

cities are powerful units in urban economic development

and the implementation of SWC planning in control of

land and financial resources. They may not be keen to

cooperate as stipulated by provincial government in

SWC plans without adequate discussion and consultation.

The provincial government lacks financial capacity and legal power to implement the SWC plan. While planners,

scholars and provincial government believe in the benefit

of SWC planning for coordinated development, lack of

the support of prefecture-level city governments, the key

players, leads to failure in the implementation of SWC

planning. Thus, both the SWC planning process, the plan

itself and the power relations between different governments are major reasons of the SWC planning failure.

New competition: defining new city-regions by prefecture cities

Although the provincial government was able to ‘‘dictate’’ a city-region plan for SWC region, it lacked the

teeth to implement the plan. The SWC plan could not

mitigate existing problems of inter-city competition. On

the contrary, it spurred a new round of competition in

the SWC region. The cities in the SWC region attempted

to formulate their own urban development strategies and

214

policies. Cities did not accept the provincial government’s arrangement as member cities of the SWC region,

even after the approval of SWC plans. They defined

their own city-regions that were different from the

SWC city-region to serve their own interests. In the

Development Forum of the Yangtze River Delta (Lake

Tai) (Changsanjiao (Taihu) fazhan luntan) sponsored

by the Suzhou government, Suzhou put forward a new

definition of city-region – City-region around Lake Tai.

This new city-region consisted of two sub-city-regions

with a total of five cities in Jiangsu and Zhejiang provinces, namely, SWC city-region and Suzhou–Jiaxing–

Huzhou city-region (Figure 3). By this definition, Suzhou

made itself the center and the head of city-regions in

southern Jiangsu and northern Zhejiang.

Like Suzhou city, Wuxi also defined its own city-region

in order to extend its development space. Wuxi also

deemed it impossible to achieve the aims of the SWC

plan due to heavy conflicts of interest among three cities.

Thus it was necessary for Wuxi to devise a new plan

regarding city-regions. A new plan – Wuxi Development

Strategic Plan was then formulated by the Wuxi government. This new plan broke down the SWC city-region

devised by the SWC Plan, replacing it with Wuxi–

Changzhou–Taizhou city-region and Suzhou–Shanghai–

Nantong city-region (Figure 3). In this city-region

classification, Wuxi claimed itself the leading city of

Wuxi-Changzhou–Taizhou city-region, but put Suzhou

under the wing of Shanghai. The reclassification

of city-regions indicates that cities did not accept the

arranged identities by the provincial government (as

member cities of the SWC city-region) and had the

intention to expand their own developmental space.

Although redefinition of city-regions was mere rhetoric

in policies and urban development strategies, it indicated

that not all cities in the region shared a common regional

identity (SWC) and competed against each other.

Why city-region planning does not work well in China the case of Suzhou–Wuxi–Changzhou: X Luo and J Shen

Figure 3 City-regions defined by Prefecture cities.

Conclusion

In western countries, city-regions are considered effective

arenas for situating the institutions of post-Fordist economic governance (Scott et al., 2001). The regional scale

is thus conceived as a ‘‘functional space’’ for economic

planning and political governance (Keating, 1998). Under

different contexts of urban and regional development,

many city-regions are being formed in China for planning

and development. Through city-region planning, a higherlevel government attempts to create a new tier of

governance, upon which it can coordinate city-region

development and promote cooperation. Unfortunately,

most grand city-region plans encounter failure in subsequent implementation. To uncover the reasons of unsuccessful planning implementation, this study selected

SWC planning for a case study. After analyzing the process

of SWC planning and assessing the implementation of

SWC plans, the following three reasons were identified.

First, city governments have acquired great administrative and economic power due to decentralization from

central and provincial governments in the reform period

(Shen, 2007). Prefecture-level cities have strong administrative power and are financially responsible for development projects such as airports. The prefecture-level city

governments, who are the key players in implementing

the SWC planning, may not have much interest in the

cooperation stipulated by provincial governments in the

SWC plan, without adequate discussion and consultation.

The provincial government lacks financial capacity and legal power to implement the SWC plan. While planners,

scholars and provincial governments believe in the benefit

of SWC planning for coordinated development, lack of

the support of prefecture-level city governments, the key

player, leads to failure in the implementation of SWC

planning.

Second, a coordinating plan should pay more attention

to the process of planning, especially building trust and

consensus among cities. Only then the direction for cooperation would become clear. But SWC planning lacks

stakeholders’ interaction and consensus building in the

planning process. In other words, ‘‘the pursuit of region’’

was not embodied in the planning process. The SWC planning process was initiated by the provincial government. It

emphasizes coordination and differs greatly from those

traditional planning efforts that focus on stimulating economic development. Thus the SWC planning is regarded

by some scholars as a new initiative of urban and regional

governance (Li, 2004). However, the ‘‘coordination’’ was

conducted by the provincial government in a top-down

manner in the planning process. The core elements of governance, stakeholders’ interaction and consensus building

(CGG, 1995; Jessop, 1998; Stoker, 1998), did not materialize in the process of planning and implementation. It is argued here that city-region planning should pay more

attention to the process of building trust and understanding, instead of simply making a plan. The government at

the higher level, while acting as a coordinator in the planning, should pay more attention to mobilizing cities at the

lower level and creating a favorable atmosphere for their

participation, interaction and exchange in the planning

process. Only in this way could a solid city-region plan

be made and successfully implemented. This is consistent

with the recent findings on regional planning in UK which

was based more on negotiation process than formal plans

in the 1990s (Wannop, 1995).

Third, the difficulty in specifying detailed content in

SWC plan is a major reason for the failure of plan imple215

Why city-region planning does not work well in China the case of Suzhou–Wuxi–Changzhou: X Luo and J Shen

mentation. As a new kind of planning, the content of the

city-region planning could not follow those traditional

planning processes such as master planning and urban system planning and should be flexible. But in SWC plans,

the content and direction of coordination proposed by

the higher-level government were either too general and

difficult to be implemented by local governments, or too

detailed, which reduced the flexibility of the plan.

Fourth, SWC planning lacks essential mechanisms of

planning and implementation. This contributed to the

unsuccessful implementation of the SWC plan. This finding is consistent with previous studies on Chinese planning

(Ng and Xu, 2000; Yeh and Wu, 1998). Thus, there is an

urgent need to establish necessary mechanisms to improve

the effectiveness of city-region planning. Standards and

procedures of city-region planning should be set up on

the definition and classification of city-regions, planning

processes, planning approval, institutions for city collaboration as well as procedures to deal with uncertainty.

The above lessons drawn from SWC planning can shed

light on other city-region planning in China and even

other countries. Chinese city-region planning can also

learn a lot from the experiences of inter-city cooperation,

urban networks and regional planning in other countries

(Cooke et al., 2004; Wannop, 1995). To achieve sustainable development of SWC city-region, we have the following suggestions.

First, the provincial government should play an enabling role in regional coordination, instead of ‘‘commander’’. The higher-level government should launch

some concrete initiatives, such as structural funds and

Interreg III in the EU, to facilitate inter-city cooperation

in the region. For example, the provincial or central governments can set up an airport cooperative to be responsible for airport development in the province and the

country without relying on local financial resources.

Second, like its western counterparts, the SWC city-region should form a city network and build its governing

capacities. To achieve this goal, the first step is to establish an urban forum which may serve as the platform for

member cities to share their views and visions on the

development of the region. After long-term exchange

among cities, a Development Commission of the SWC

City-region should be established to be in charge of regional and coordinative matters in the region. This commission should have a flexible governance structure,

consisting of a general assembly, a steering group and

thematic cooperation groups. The establishment of such

commission represents the institutionalization of an urban network. Through the above institution-building,

SWC plans can be implemented effectively, and the

SWC city-region will become an integrated and promising regional entity with enhanced cooperation among

member cities.

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by the Urban China Research

Network and the National Natural Science Foundation of

China (NSFC Grant No. 40601031). The authors would

like to thank anonymous referees and Professor Andrew

216

Kirby for their constructive comments to improve the

manuscript.

References

Abramson, D B, Leaf, M and Ying, T (2002) Social research and the

localization of Chinese urban planning practice: Some ideas from

Quanzhou, Fujian. In The New Chinese City: Globalizaiton and

Market Reform, J R Logan (ed.). Blackwell, Malden.

Arndt, M, Gawron, T and Jahnke, P (2000) Regional policy through cooperation: from urban forum to urban network. Urban Studies 37(11),

1903–1923.

CGG (The Commission on Global Governance) (1995) Our Global

Neighbourhood: The Report of the Commission on Global Governance. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Cooke, P, Davies, C and Wilson, R (2004) Urban networks and the new

economy: the impact of clusters on planning for growth. In Urban

Competitiveness: Policies for Dynamic Cities, I Begg (ed.), pp. 233–

256. The Policy Press, Bristol.

Gao, R (2004) Study on economy development of Shanghai metropolitan

area. City 3, 14–18.

Heeg, S, Klagge, B and Ossenbrügge, J (2003) Metropolitan cooperation

in Europe: theoretical issues and perspectives for urban networking.

European Planning Studies 11(2), 139–153.

Jessop, B (1998) The rise of governance and the risks of failure: the case

of economic development. International Social Science Journal 50(1),

29–45.

JSCC (Jiangsu Construction of Commission), JSURPI (Jiangsu Urban

and Rural Planning Institute), 2002. Suzhou–Wuxi–Changzhou

Urban Region Plan. Nanjing: JSCC and JSURPI.

JSSB (Jiangsu Statistical Bureau) (2003) Statistical Yearbook of Jiangsu

2003. China Statistical Publishing House, Beijing.

Keating, M (1998) The New Regionalism in Western Europe: Territorial

Restructuring and Political Change. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham.

Kloosterman, R C and Lambregts, B (2001) Clustering of economic

activities in polycentric urban region: the case of the Randstad. Urban

Studies 38(4), 717–732.

Leaf, M (1998) Urban planning and urban reality under Chinese

economic reforms. Journal of Planning Education and Research

18(2), 145–153.

Li, J (2004) Study on Competitive Regional Governance: A Case Study of

the Yangtze River Delta. Unpublished Master’s Thesis, Nanjing

University, Nanjing.

Liu, J (1996) Theories and Practices of Chinese Administrative Areas.

East China Normal University Press, Shanghai.

Ng, M K and Tang, W S (1999) Urban system planning in China: a case

study of the Pearl River Delta. Urban Geography 20(7), 591–616.

Ng, M K and Tang, W S (2004a) The role of planning in the development

of Shenzhen, China: rhetoric and realities. Eurasian Geography and

Economies 45(3), 190–211.

Ng, M K and Tang, W S (2004b) Theorising urban planning in a

transitional economy: the case of Shenzhen, People’s Republic of

China. Town Planning Review 75(2), 173–203.

Ng, M K and Xu, J (2000) Development control in post-reform China:

the case of Liuhua Lake Park, Guangzhou. Cities 17(6), 409–418.

Qian, Y and Xie, S (2004) To promote the competitiveness of

metropolitan region to achieve its sustainable development. East

China Economic Management 18, 4–7.

Scott, J, Agnew, J and Soja, E W (2001) Global city-regions. In Global

City-regions: Trends, Theory, Policy, A J Scott (ed.), pp. 11–30.

Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Shen, J (2007) Scale, state and the city: urban transformation in post

reform China. Habitat International 31(3–4), 303–316.

Shi, Y L and Hamnett, C (2002) The potential and prospect for global

cities in China: in the context of the world system. Geoforum 33, 121–

135.

Stoker, G (1998) Governance as theory: five propositions. International

Social Science Journal 50(1), 17–28.

Walder, A G (1995) Local governments as industrial firms: an organizational analysis of China’s transitional economy. American Journal

of Sociology 101(2), 263–301.

Wang, X (2003) Practice and thinking of urban region planning. City

Planning Review 27(6), 51–54.

Why city-region planning does not work well in China the case of Suzhou–Wuxi–Changzhou: X Luo and J Shen

Wannop, U A (1995) The Regional Imperative: Regional Planning and

Governance in Britain, Europe and the United States. Jessica Kingsley

Publishers and Regional Studies Association, London.

Wei, Y H D (2001) Decentralization, marketization, and globalization:

the triple processes influencing regional development in China. Asian

Geographer 20(1&2), 7–23.

Wei, Y H D and Li, W (2002) Reforms, globalization, and urban growth

in China: the case of Hangzhou. Eurasian Geography and Economics

43(6), 459–475.

Wu, F (2000) The global and local dimensions of place-making: remaking

Shanghai as a world city. Urban Studies 37(8), 1359–1377.

Xu, J and Ng, M K (1998) Socialist urban planning in transition: the case

of Guangzhou, China. Third World Planning Review 20(1), 35–51.

Xu, J and Yeh, A G O (2005) City repositioning and competitiveness

building in regional development: new development strategies in

Guangzhou, China. International Journal of Urban and Regional

Research 29(2), 283–308.

Yao, X (2007) Construction of Wuxi new airport will be completed and

will begin operation on 28 September. CAAC Journal, 27 July 2007.

Yeh, A G O and Wu, F (1998) The transformation of the urban planning

system in China from a centrally-planned to transitional economy.

Progress in Planning 51(3), 167–252.

Zhang, J, Shen, J, Wong, K Y and Zhen, F (2002) The administrative

division and regional governance in urban agglomeration areas. City

Planning Review 25(9), 40–44.

Zhang, T (2000) Land market forces and government’s role in sprawl: the

case of China. Cities 17(2), 123–135.

Zhang, T (2002) Challenges facing Chinese planners in transitional

China. Journal of Planning Education and Research 22, 64–67.

Zhang, W (2003) The basic concept, characteristics and planning of

metropolitan regions in Jiangsu. City Planning Review 27(6), 47–

50.

Zhu, J (1999) Local growth coalition: The context and implications of

China’s gradualist urban land reforms. International Journal of Urban

and Regional Research 23(3), 534–548.

Zhu, J (2004) Local development state and order in China’s urban

development during transition. International Journal of Urban and

Regional Research 28(2), 424–447.

217