Impact of Supermarket Expansion in the Convenience Retailing Sector

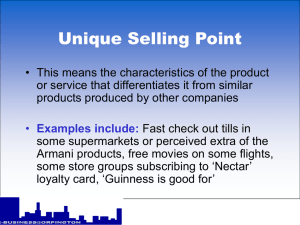

advertisement