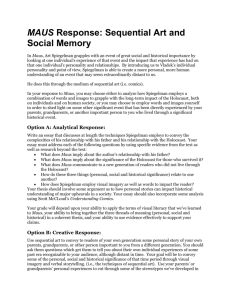

View/Open - ResearchArchive - Victoria University of Wellington

advertisement