EWR Spring 2008 issue PDF - Washington State University

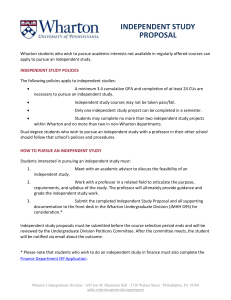

advertisement