Consensual vs

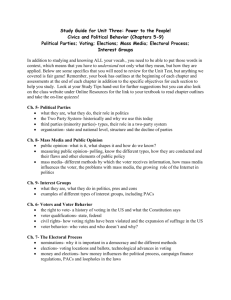

advertisement