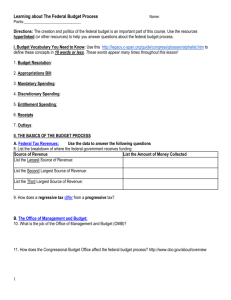

A survey of the effects of discretionary fiscal policy

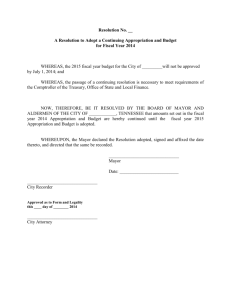

advertisement