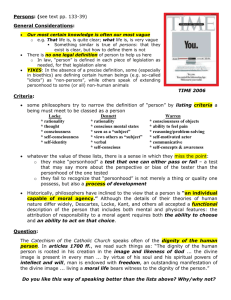

The Conception View of Personhood

advertisement