"The Rocking-Horse Winner" Analysis | College English Article

advertisement

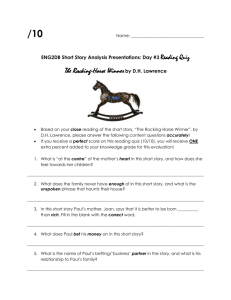

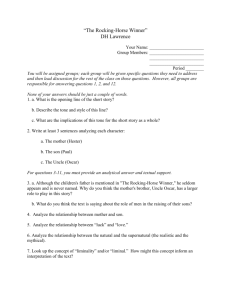

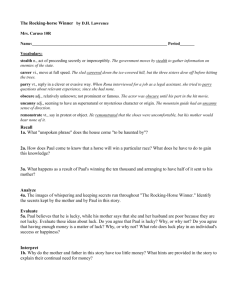

Fancy or Imagination? "The Rocking-Horse Winner" Author(s): W. R. Martin Source: College English, Vol. 24, No. 1 (Oct., 1962), pp. 64-65 Published by: National Council of Teachers of English Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/373851 . Accessed: 07/09/2011 20:07 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org. National Council of Teachers of English is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to College English. http://www.jstor.org 64 COLLEGE case."2 This charge has been repeated recently in a more elaborate form by Marvin Mudrick (Nineteenth Century Fiction, March 1957) who sarcastically refers to Conrad's exaggerated reputation as a "poet in fiction," and objects to the "unctuous thrilling rhetoric," the "colorful irrelevance of metaphor" in The Nigger of the "Narcissus." Some of the liveliest skirmishes among recent writers on Conrad have been fought on the grounds of his grandiloqu2AbingerHarvest (New York, 1936), p. 140. ENGLISH ence and symbolism.3 But "Typhoon" rarely figures in this critical quarreling because its precision makes it one of Conrad's least problematical works. It remains one of the few Conrad stories which nearly everyone likes: which is one way of saying that it is more artful or unified, but obviously less ambitious and profound than, say, The Nigger or Lord Jim. 'See Ian Watt, "Conrad Criticism and The Nigger of the "Narcissus," NCF, 12 (March 1958), 257-283. FANCY OR IMAGINATION? "THE ROCKING-HORSE WINNER" W. R. MARTIN D. H. Lawrence's "The Rocking-Horse Winner" appears in several anthologies,1 and I think it worth while to defend it against the strictures of F. R. Leavis (D. and Graham H. Lawrence: Novelist) Hough (The Dark Sun). This can be done by starting with a close analysis of a paragraph to be found near the end of the story: Then suddenly she switched on the light, and saw her son, in his green pyjamas, madly surging on the rocking-horse. The blaze of light suddenly lit him up, as he urged the wooden horse, and lit her up, as she stood, blonde, in her dress of pale green and crystal, in the doorway. The sudden switching on of the light, which "lit him up" and "lit her up, as she stood . . . in the doorway," invites our attention to a heraldically graphic picture that contains the central meaning of the story. That both mother and son are in green marks the culmination of the movement. This is further dramatised and elu1The Rinehart Book of Short Stories (1952), D. H. Lawrence: Selected Poetry and Prose (1957), The Portable D. H. Lawrence (1947). Professor Martin teaches English at the University of Waterloo, Ontario, and his special interest is Jane Austen. A South African who emigrated with his family to Canadain 1961, he is the author of several articles published in English Studies in Africa. cidated by "madly" (supported by "surging" and even by "blaze"-a word used several times for the look in the boy's eyes) which is offered in its loose colloquial sense as a description of the boy's motion, but must be taken to refer quite literally to his condition. His madness is an infection caught from his mother, whose hysterical whisper, "There must be more money! There must be more money!" issues finally in the son's "Did I say Malabar, mother? Did I say Malabar?" and prefigures at the beginning of the story the frantic iteration in the rocking-horse's motion. Indeed the whisper is echoed by it: "It came whispering from the springs of the still-swaying rocking-horse." To complete the definition of the climax, the mother's "crystal" dress reflects the hardness "at the centre of her heart," and a few lines after our paragraph we are told that the boy's eyes (eyes are an important index throughout) "were like blue stones" and that the mother felt her heart had "turned actually into a stone." All this is, perhaps, no more than "skilful," which is as far as Hough will go in praise of the story. But "skilful" does less than justice to it, as I hope to show. Our paragraph refers to the toy as a "rocking-horse"-this is the ninth time it is so called-and in the next line it is a "wooden horse." "Wooden" has appeared twice before, but its definitive connotative ROUND force has not been felt because there has not been this juxtaposition.Now the modulation points with delicately controlled emphasisto the significance of the rockinghorse in the story. The simple but decisive effect of "wooden" is to make clear a distinction that we now see to have been implicit in the story from the beginning. The real and lively race-horses,whose names-Sansovino, Daffodil, Lancelot, Mirza, Singhalese,Blush of Dawn, Lively Spark-resound insistently through the story, represent with almost crude emblematic clarity the possibilitiesin a fully lived life and are in ironic contrast to the wooden horse, which, with its "springs,""mechanicalgallop"and "arrested prance"is the symbol of the unlived, merely mimetic, life of Paul's parents. The toy horse "doesn't have a name" because it is a nonentity, a substitute: "Till I can have a real horse, I like to have some sort of animal about." The rocking-horse is seven times referred to simply as the "horse,"and this unobtrusively establishesan ironic tension between real life and the unliving imitation. The tale presents an aspect of the rocking-horse which compels attention. It appears in our paragraphin "madly surging" and "urges."The mother hears a "soundless noise," "something huge, in violent hushed motion"-here again the rocking is linked with the whispering, which "the children could hear all the time, though nobody said it aloud"-and sees him "plunging to TABLE 65 and fro." For all this frenzied effort the horse rocks backwards and forwards on the same spot, "still-swaying." Lawrence does not have to score this heavily, but the rocking motion evokes with poetic economy and precision the futility of the parents, whose "prospects never materialised."They buy "splendidand expensive toys" (substitutes, in this story, for real things) for their children; they spend lavishly on themselves in a desperatestruggle "to keep up" their social position. Neither the toys nor the social position give real satisfaction and the parents are condemned to ever more frantic and meaningless repetition. This is seen in the mother: she clamours for money, but as soon as she gets the ?5,000 she is back where she was before, wanting more money more desperately. The parents too are on a rocking-horse, and they are not individuals-like the wooden horse they have no names-but representativesof a large section of bourgeois society. With so much significant meaning so successfully conveyed through objective correlatives, I cannot agree with Hough that the story is a product of "fancy not imagination," or share Leavis' exasperation that it is "so widely regarded (especially in America, it would seem)." Both Hough and Leavis say that the story is not representativeof Lawrence,but it seems to me to be about, and to dramatizemost forcefully, one of his central concerns: the nature and nemesis of unlived lives. New Address for College English Manuscripts Editor, College English, Department of English, University of Chicago Chicago 37, Illinois