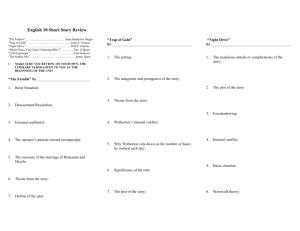

THE COMPARISON OF THEME IN “THE ROCKING HORSE

advertisement