beyond big 5 leader goal orientation

advertisement

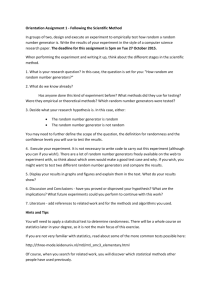

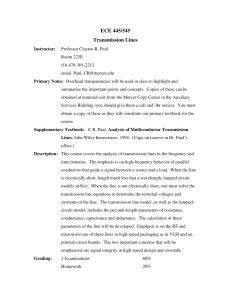

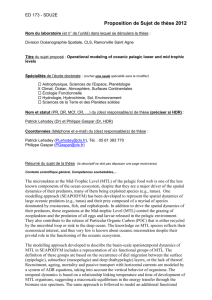

HUMAN PERFORMANCE, 20(4), 317–343 Copyright © 2007, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. Beyond the Big Five: Leader Goal Orientation as a Predictor of Leadership Effectiveness Joseph W. Hendricks and Stephanie C. Payne Texas A&M University This study examined proximal traits as mediators of the relationships between distal traits and leadership effectiveness. Specifically, we examined goal orientation, leadership self–efficacy, and motivation to lead (MTL) as antecedents of leadership effectiveness, after controlling for the Big Five personality traits. We tested our hypotheses with a sample of 100 leaders of four-person teams performing a manufacturing task in a laboratory setting. Consistent with expectation, leadership self-efficacy partially mediated the relationships between learning goal orientation and Affective-Identity MTL as well as Social-Normative MTL, after controlling for the Big Five. Noncalculative MTL related significantly to averaged team member ratings of leadership effectiveness, after controlling for both the leader’s and the team member’s personality. These results help aid in our understanding of why leader traits relate to leadership effectiveness. The study of leadership in organizations has been prevalent since the beginning of the 19th century. Thousands of research studies have focused on leadership phenomenon (Yukl, 1989) in part to enhance our ability to predict leadership effectiveness. A recent meta-analysis revealed that cumulatively the Big Five personality variables have a multiple correlation of .39 with leadership effectiveness (Judge, Bono, Ilies, & Werner, 2002). Although their work aided in demonstrating an empirical relationship between the Big Five and leadership criteria, their examination did not reveal why these relationships exist. As a result, the question of why individual differences predict leadership effectiveness remains unanswered. Whereas the Big Five classification captures a broad array of dispositional traits, it is not a comprehensive taxonomy of all individual difference characterisCorrespondence should be sent to Joseph W. Hendricks, Mail Stop 4235, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, 77843–4235. E-mail: jwh@neo.tamu.edu 318 HENDRICKS AND PAYNE tics that have been or could be related to leadership effectiveness. For example, one motivational construct that has not been extensively explored as an antecedent of leadership effectiveness is goal orientation (Dweck, 1986). Goal orientation describes an individual’s predisposition to set certain types of goals in achievement situations. We propose that goal orientation is indirectly related to leadership effectiveness through more proximal individual difference characteristics. Thus, the purpose of the study presented here is to examine the extent to which goal orientation predicts leadership effectiveness above and beyond the Big Five. We also respond to calls for research to explain why leader traits predict leadership effectiveness (e.g., Judge et al., 2002). To do this, we build on Chan and Drasgow’s (2001) theoretical framework for explaining the role of individual differences in leadership development. Specifically, we propose that goal orientation dimensions indirectly relate to leadership effectiveness, through the mediating variables leadership self-efficacy (LSE) and motivation to lead (MTL) as depicted in Figure 1. We include the Big Five personality variables as the most distal traits inferring that their influence is further mediated by goal orientation. After briefly reviewing trait theory, we describe goal orientation and these mediating variables that help to explain why we expect goal orientation to relate to leadership effectiveness. TRAIT THEORY OF LEADERSHIP Trait approaches for explaining leadership behavior and effectiveness have had the longest and arguably least successful history compared to other leadership theories. Efforts to identify a list of essential leader traits were not very fruitful. There were a number of limitations to early trait leadership research that contributed to the lack of empirical support for trait theory. First, researchers focused on individual, bivariate correlations between individual traits and leadership (Lord & Hall, 1992). Also, until relatively recently, we lacked a well-accepted model of personality to aid in the development of trait models of leadership (House & Aditya, 1997). Thus we take a more holistic approach simultaneously examining multiple individual differences as predictors of leadership effectiveness including the broad Big Five personality traits. Further, we examine both leader and team member traits in an effort to determine if leader traits predict leadership effectiveness beyond group member traits (Piccolo & Judge, 2006). Second, previous trait studies lacked a theoretical explanation for why certain traits predict leadership. Yukl (1998) advocated seeking processes that mediate the relationship between traits and leadership effectiveness. “Traits offer the potential to explain why people seek leadership positions and why they act the way they do when they occupy these positions” (Yukl & Van Fleet, 1992, p. 153). We build on 319 FIGURE 1 Model of hypothesized relationships among leader proximal and distal traits and leadership effectiveness. 320 HENDRICKS AND PAYNE Chan and Drasgow’s (2001) framework, which proposed LSE and MTL as important mediators of the relationships between more stable/distal individual differences and leader effectiveness. Third, trait researchers did not differentiate between three leadership criteria: leadership perceptions, leader emergence, and leadership effectiveness (Lord, DeVader, & Alliger, 1986). In the study presented here, we focus on leadership effectiveness, which can be defined as (a) how well the leader facilitates “the movement of a group of people toward a common goal or objective” (House & Podsakoff, 1994, p. 46), as well as (b) the consequences of the leader’s actions (i.e., team outcomes; Yukl, 1998). The former indicator is typically an aggregation of subjective ratings provided by each of the individual followers that have been shown to empirically converge. The latter indicator is usually a more objective and distal measure than the former. In summary, our study builds on Chan and Drasgow’s (2001) integrative theoretical framework for understanding the relationship between individual differences and leadership effectiveness. It also addresses limitations of previous trait-based leadership studies by including multiple individual differences for the leader and the team members, examining theoretically driven mediator variables, and focusing on leadership effectiveness. We now turn to the individual difference characteristics we propose as distal antecedents of leadership effectiveness. GOAL ORIENTATION Goal orientation describes an individual’s disposition to set certain types of goals in achievement-related settings affecting what type of feedback is sought and how feedback is interpreted. This disposition influences behavior on task performance by affecting the way in which a person reacts to task difficulty (Brett & VandeWalle, 1999; Dweck, 1986; Dweck & Leggett, 1988; Elliott & Dweck, 1988; Farr, Hofmann, & Ringenbach, 1993). Taking a social–cognitive approach to motivation (e.g., Markus, 1977), Dweck and Leggett described two different types of goals. Performance goals are goals to successfully complete a task and are norm-referenced. Individuals with a strong performance goal orientation (PGO) are concerned with judgments of peers as well as superiors and want to be able to succeed at whatever tasks they perform. They will often engage in tasks they know they can complete or set goals they know are obtainable. In addition, these individuals are characterized as having a fear of failure and experiencing escapist thoughts or thoughts of quitting the task at hand (Button, Mathieu, & Zajac, 1996). Learning goals are goals to further develop knowledge or skills with the intention to ultimately “master” the given task and are self-referenced. Individuals with a strong learning goal orientation (LGO) have the desire to learn about new material GOAL ORIENTATION AND LEADERSHIP 321 and master task performance. They are not concerned with their relative performance to others but their absolute performance and furthering their understanding of some content or task (Dweck & Leggett, 1988). Initially these goals and corresponding goal orientations were conceptualized as two different ends of the same continuum. Now, however, they are believed to be separate dimensions (Button et al., 1996; Payne, Youngcourt, & Beaubien, in press). In fact, the dimensionality of the PGO dimension has been further examined (Elliot & Harackewitz, 1996; VandeWalle, 1997). For example, VandeWalle divided PGO into two separate dimensions, performance-prove (PPGO) and performance-avoid goal orientations (PAGO). He suggested the division is a better representation of the divergent response patterns typically associated with a strong PGO. The PPGO dimension describes efforts of individuals to try to appear better than their reference group. The PAGO dimension describes efforts of individuals to avoid negative evaluations and criticisms of others. Previous Goal Orientation and Leadership Studies Little research has been conducted linking goal orientation to leadership, and no studies have examined leader goal orientation as an antecedent of leadership effectiveness. Instead, most research linking these two constructs has focused on the extent to which leadership variables predict followers’ goal orientation (e.g., Dragoni, 2005; Gorenflo-Gilbert, 1999; Schwager, 1997). We found only one study that examined leader’s goal orientation as an independent variable. Although not specifically hypothesized, McCormick (1999) found leader LGO was significantly related to both pre- and posttraining LSE. The study presented here extends this research by also examining the leader’s PGO, MTL, and leadership effectiveness. MEDIATORS OF THE INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCE-LEADERSHIP EFFECTIVENESS RELATIONSHIP Recently, Chan and Drasgow (2001) proposed a theoretical framework for understanding the role of traits in leadership behavior by integrating the process of leader development with leader performance. Their framework proposed that noncognitive individual differences such as personality relate to leader effectiveness through the leader’s LSE and MTL, which in turn relate to participation in leadership roles and activities, facilitating leadership development. We describe these theoretically driven mediator variables in the next section. 322 HENDRICKS AND PAYNE Leadership Self-Efficacy Building on Langston and Sykes (1997) findings that the Big Five variables are correlated with individual beliefs, Chan and Drasgow (2001) proposed that personality and values lead to LSE. This construct is the result of the application of Bandura’s (1997) self-efficacy theory to the leadership literature. Kane (1999) defined LSE as “one’s perceived self-capability to perform cognitive and behavioral functions required to effectively perform a specific leadership task” (p. 5). Kane contended that LSE is similar to task-specific self-efficacy except that team members also influence it. The leader must realize his or her capability is affected by team members or followers and must regulate his or her thoughts and actions as well as team activities. In other words, team composition, processes, and the environment for a specific task and/or situation influence task-specific LSE. Kane, Zaccaro, Tremble, and Masuda (2002) found that LSE related significantly to leader goal level, leader strategies, and functional leadership behaviors. Chan and Drasgow (2001) proposed that LSE is a proximal antecedent of MTL and found LSE to be empirically related to two MTL factors. They also found that all of the Big Five were positively related to LSE. Consistent with the positive influence of specific self-efficacy on performance (Stajkovic & Luthans, 1998), high levels of LSE are expected to result in higher levels of engagement in leadership opportunities and higher levels of leadership effectiveness. Motivation to Lead MTL has been defined as an individual difference variable that determines whether individuals seek out leadership positions, and if they do, how much effort they exert to perform their leadership duties at a high level (Chan & Drasgow, 2001). Chan and Drasgow conceptualized MTL as a three-dimensional construct and demonstrated empirical support for this structure. The first factor is termed Affective-Identity MTL. An individual with a high score on this dimension is someone who generally likes to lead. The second factor, Social-Normative MTL, is MTL out of a sense of duty or responsibility. The third factor, Noncalculative MTL, is of particular interest in this study. One with a high level of Noncalculative MTL does not try to weigh the costs versus the benefits of assuming a leadership role. Because leadership roles usually have a number of potential costs (i.e., time, large amount of responsibility), an individual who is calculative of the costs–benefits ratio will presumably not want to assume the leadership role. Chan and Drasgow (2001) proposed that MTL is a direct outcome of LSE, and it is also directly influenced by personality and values. They found that LSE was significantly related to both the Affective-Identity and Social-Normative MTL factors, indicating that those that have confidence in their leadership ability are more GOAL ORIENTATION AND LEADERSHIP 323 likely to want to lead and feel the need to lead out of a sense of duty. They also found empirical evidence for a direct effect of the Big Five on the MTL factors. INTEGRATION OF LITERATURE AND HYPOTHESES Building on Chan and Drasgow’s (2001) theoretical framework, we propose the relationships between goal orientation and leadership effectiveness can also be explained by the motivational mechanisms LSE and MTL. For individuals who are assigned leadership roles, as they were in our study, MTL captures the intensity of his or her effort of leading and persistence as a leader (Chan & Drasgow, 2001). Conceptually the three goal-orientation dimensions can be linked both directly and indirectly to MTL and to LSE. McCormick (1999) suggested that those with a strong LGO would sustain or improve their efficacy expectations due to their nonnegative view of mistakes. Conversely, individuals with a strong PGO view mistakes as a limitation to their capabilities and therefore are less likely to enhance efficacy judgments. Empirically, LGO has shown consistently positive relationships with specific self-efficacy (e.g., Bell & Kozlowski, 2002; Kozlowski et al., 2001; Phillips & Gully, 1997). We test this relationship with specific self-efficacy for leadership roles (LSE). Given the relationships Chan and Drasgow (2001) revealed between the Big Five and LSE as well as the Big Five and MTL and Judge et al.’s (2002) meta-analytic findings that all of the Big Five are related to leadership effectiveness, we examine the extent to which goal orientation predicts LSE and MTL above and beyond the Big Five. H1: LGO will positively relate to LSE above and beyond the Big Five. LSE might also facilitate a relationship between LGO and both Affective-Identity and Social-Normative MTL. In other words, individuals with high levels of LGO are likely to have high levels of Affective-Identity MTL and Social-Normative MTL, because they are likely to be efficacious about their leadership abilities. H2a: LSE will partially mediate the positive relationship between LGO and Affective-identity MTL. H2b: LSE will partially mediate the positive relationship between LGO and Social-normative MTL. Both PGO dimensions are expected to indirectly relate to leadership effectiveness as well. The basis for these relationships is through the Noncalculative MTL factor. Those who are motivated to lead for Noncalculative reasons do not readily calculate the possible consequences of leadership behaviors. In other words, they 324 HENDRICKS AND PAYNE are less concerned about or “not calculative about, the costs of leading relative to the benefits (i.e., noncalculative MTL)” (Chan & Drasgow, 2001, p. 482). Those with a high level of PPGO are motivated to demonstrate their abilities to others. Accordingly, these individuals are likely to calculate the benefits of leading (e.g., the extent to which they can demonstrate their abilities to others). According to Chan and Drasgow, calculative individuals will be less motivated to lead due to the high costs of leading. Therefore, we propose that PPGO will be negatively related to Noncalculative MTL. H3a: PPGO will negatively relate to Noncalculative MTL above and beyond the Big Five. Similarly, individuals with high levels of PAGO are motivated to avoid negative feedback and criticism. They will be motivated to calculate the costs and consequences of assuming a leadership role (e.g., responsibility, accountability) to avoid negative feedback. In addition, PAGO is positively related to negative affect (Payne et al., in press), which in turn is related to more careful information processing (Clore, Schwarz, & Conway, 1994; Forgas, 1995; Isen, 1987) and calculative decision making. Thus, the inclination to calculate will make individuals with high levels of PAGO less motivated to lead. Therefore, we expect PAGO to also be negatively related to Noncalculative MTL. H3b: PAGO will negatively relate to Noncalculative MTL above and beyond the Big Five. To establish that goal orientation is a distal antecedent of leadership effectiveness, each of the MTL factors must be related to leadership effectiveness. Chan and Drasgow (2001) did not predict that MTL would be directly related to leadership effectiveness; however, they did not discount the possibility. In addition, their data did not permit an examination of this relationship, as they did not measure leadership effectiveness. They did, however, demonstrate that MTL was a significant predictor of leadership potential ratings. We expect each of the three MTL factors to positively relate to leadership effectiveness. Those who generally enjoy leading (Affective-Identity MTL) will be better leaders than those individuals that do not enjoy or like leading. In addition, individuals who are less likely to calculate the costs–benefits ratio (Noncalculative MTL) are more likely to be effective leaders. Finally, those who feel a sense of duty to lead (Social-Normative MTL) are more likely to be effective leaders than those who do not feel a sense of duty to lead. We test these relationships after controlling for the leader’s and the team members’ Big Five personality characteristics in an effort to address the lack of research examining the influence of leader traits over and above follower traits (Piccolo & Judge, 2006). GOAL ORIENTATION AND LEADERSHIP 325 H4a: Affective-Identity MTL will positively relate to leadership effectiveness above and beyond the leader’s and team members’ Big Five. H4b: Noncalculative MTL will positively relate to leadership effectiveness above and beyond the leader’s and team members’ Big Five. H4c: Social-Normative MTL will positively relate to leadership effectiveness above and beyond the leader’s and team members’ Big Five. In summary, the goal of our study is to examine the relationship between goal orientation and leadership effectiveness via two motivational mechanisms. We conduct a conservative test of these relationships by controlling for distal traits. METHOD Participants Four hundred undergraduate students enrolled in introductory psychology participated in this laboratory study voluntarily as one option for fulfilling a course research requirement. The participants were recruited through the participant pool of the psychology department at a large, southwestern university. The ages of participants ranged from 17 to 24 (M = 19.02, SD = 1.11) and the number of men and women was essentially equal (53% male). The majority of the participants were White (80.8%). The participants completed the study in four-person teams consisting of one leader and three team members. A power analysis with a power of .80 revealed that a minimum of 96 leaders were necessary to obtain correlations of .30 (a medium effect size; Cohen, 1988) or higher. Accordingly, data were collected for 100 teams. The roles of leader and team member were determined before the study began based on how the participants signed-up for the session. This ensured no one knew beforehand that they were going to be placed in a leadership position. The demographics of the sample of leaders were very similar to the demographics of the rest of the participants. Approximately one half of the leaders were male (53%). On average, the leaders were 19.08 years of age, and the majority was White (76%). Measures Big Five personality dimensions. Saucier’s (1994) Mini-Markers was used to measure the Big Five personality factors. This scale consists of 40 adjectives and is an abbreviated list of Goldberg’s (1990) 100 adjectives. The participants rated how well the adjectives described themselves using a 5-point accuracy scale. 326 HENDRICKS AND PAYNE Goal orientation. Individuals’ dispositional goal orientation was assessed using a modified version of VandeWalle’s (1997) 13-item, three-dimensional work domain measure. References to work were removed from the items. Five items measured LGO, 4 items measured PPGO, and 4 items measured PAGO. A 5-point Likert agreement scale was used as the response format for each of the items. Motivation to lead. Chan and Drasgow’s (2001) 27-item MTL measure was used to assess MTL. The measure contained three nine-item scales: Affective-Identity MTL, Noncalculative MTL, and Social-Normative MTL. A 5-point Likert agreement scale was used for each item. Leadership self-efficacy. The measure for LSE was also developed by Chan and Drasgow (2001) based on a measure constructed by Feasel (1995). This instrument contained six items that were responded to on a 5-point Likert agreement response scale. Leadership effectiveness. We obtained two measures of leadership effectiveness: team member ratings of the leader’s performance in the team task (averaged within each team) and team performance on the experimental task (profit level). Using a 5-point agreement scale, each team member rated his or her team’s leader on a 17-item instrument developed by Kane (1999) for the experimental task used in this study. A sample item read, “Overall, I thought the leader did a good job.” A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) revealed two items had weak loadings on the latent construct, so we dropped them from further analyses.1 A CFA of the remaining 15 items supported a unidimensional structure, χ2 (90, N = 300) = 339.07, p < .01; Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) = .98, comparative fit index (CFI) = .98, incremental fit index (IFI) = .98, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.08. We then tested to see if we had sufficient agreement within each team to aggregate the team members’ ratings of leadership effectiveness to the team level. Both within-team agreement and interrater reliabilities were estimated (cf. Bliese, 2000, and James, Demaree, & Wolf, 1984). Within-team interrater agreement (rwg(j) = .93) was substantially high, indicating on average team members were uniform in their assessment of the leader’s performance. In addition, intraclass correlations (ICC[1] = .46 and ICC[2] = .72) indicated rater consistency across items. Thus, the mean of the team members’ ratings within each team were used to represent leader effectiveness. 1The following two items were dropped from the groups’ ratings of leadership effectiveness inventory: “This leader assigned group members particular roles for performing the task” and “The leader did things his/her own way.” GOAL ORIENTATION AND LEADERSHIP 327 Experimental Task Participants completed an experimental task titled “The Manufacturing Game” (Kane et al., 2002; Zaccaro, Foti, & Kenny, 1991) in four-person teams. Each team was given the task of building products and selling them for profit. The overall goal of the task was to maximize team profit by buying at lower prices and selling at higher prices, as the market prices changed during the task. The products were built from raw materials (LEGO® blocks), and the design of three products was given to all participants in two- and three-dimensional formats. Correspondingly, the task could be described as an “executing performance task” (McGrath, 1984) that is somewhat additive in that performance represents the sum of each member’s individual contribution (Steiner, 1972), although leader contributions were not exactly the same as the team members’ contributions. Some interdependence between the leader and the team members was uniformly imposed across all teams by only permitting the team members to build the products. The leader could place orders and sell products, but she or he could not build any products. Using existing team typologies, the teams in our study would be classified as hierarchical production teams (Devine, 2002; Hackman, 1990; LePine, Hollenbeck, Ilgen, & Hedlund, 1997). Procedure Ten hypothesis-blind research assistants were trained to follow a tightly scripted protocol and collected all of the data for the study. The leaders were required to arrive 45 min prior to the other participants for pretraining on the task. Upon arrival, the leader completed a series of individual difference measures. Next, the leader was given a set of instructions indicating she or he was going to participate in the Manufacturing Game, how to complete the game, and the objective of the game. She or he was also provided with an ordering form, market prices, and models of the products. The leader was allotted 5 min to prepare for the task and 15 min of production time. The experimenter distributed supplies and bought finished products at the specified market price, which changed every 5 min. If the products were not built to exact specifications, they were rejected and returned for “repairs.” The leader’s performance (profit) on the task was recorded to be used as a covariate when predicting team performance. Concurrent with the leader completing the experimental task, the additional participants (team members) arrived for the session. The team members completed the same battery of individual difference measures that the leader previously completed while the leader took a short break. Upon completion of the self-report inventories, the team was informed that they were going to perform the Manufacturing Game as a team and introduced to their designated leader. At this time, the experimenter reminded the team members, as indicated in their informed consent, the three most profitable teams were eligible for a $100 prize ($25 each). The leader was then given 328 HENDRICKS AND PAYNE a second set of instructions for the Manufacturing Game and told she or he was responsible for communicating the instructions to her or his team members. The leader was instructed that this time she or he could not physically contribute to the building of the products. Each leader was given 10 min to explain the task and plan for production, followed by 20 min of production time. Again, the market buying prices and selling prices changed every 5 min throughout the 20-min performance phase. The leader was given the changes in market information at the beginning of the task. The leader and team members were permitted to ask the experimenter for time checks throughout the exercise, but they were not permitted to wear a watch in order to maintain standardization of resources across participants. As before, raw materials were purchased using an order form and inaccurate products were sent back for “repairs.” Once the time allotted had passed, the team members independently rated the effectiveness of the leader. Team profit was calculated by subtracting the money spent on raw materials from total revenue. The experimenter used a log sheet to record all transactions. Level of Analysis All participants completed the individual difference measures; thus, both leader and follower proximal and distal traits were assessed. The leadership role in this study was determined relatively randomly, so there was no reason to expect leaders to be different from the team members on the variables examined. We conducted a series of independent t tests to confirm this assumption and found that the leaders did not vary significantly from the team members on any of the focal variables examined in this study. All hypotheses were tested with a sample size of 100. Team member characteristics (e.g., Big Five) were averaged within each team. RESULTS Descriptive statistics, reliability estimates, and intercorrelations among the variables are presented in Tables 1 and 2 for the leader and team members, respectively. Despite Chan and Drasgow’s (2001) conceptual distinction between the MTL factors and LSE, the correlations between LSE and the MTL factors were relatively high (ranging .39–.68) calling into question the discriminability of these constructs. However, a CFA demonstrated that a four-factor model, χ2(489, N = 400) = 1,069.31, p < .01 (χ2/df = 2.19; TLI = .85, CFI = .86, IFI = .86, RMSEA = .06), fit the data better than a single-factor solution, χ2(495, N = 400) = 1,992.21, p < .01 (χ2/df = 4.025; TLI = .62, CFI = .65, IFI = .65, RMSEA = .09).2 Also, the dif2We used the full sample (N = 400) for the CFA to maximize the sample size for each parameter that was estimated. 329 M 1 2 0.52 (.78) 0.61 .38 (.79) 0.67 .32 .43 0.73 .35 .09 0.51 .32 .13 0.56 .12 .26 0.65 .05 .03 0.71 –.09 –.10 0.53 .21 .35 0.56 .05 .25 0.43 .23 .31 0.45 .24 .28 5,166.00 .00 .02 0.65 .09 .08 17,856.12 –.12 .02 SD 4 5 6 (.78) .23 (.86) .08 .18 (.73) .19 .35 .27 (.78) –.25 .09 .19 .31 –.25 –.19 –.05 –.20 .26 .39 .27 .40 .13 .40 .19 .40 .29 .30 .28 .29 .28 .33 .24 .40 –.13 –.12 .08 .20 .03 .30 .06 .16 –.02 .04 –.04 .09 3 (.71) .36 .16 .31 .04 .29 .22 .00 .17 7 (.78) –.19 –.09 –.17 –.11 .02 –.08 –.11 8 (.81) .68 .39 .57 .03 .29 .12 9 (.83) .22 .50 .14 .24 .19 10 12 13 14 (.79) .38 (.72) .01 –.08 .23 –.01 .17 (.93)a .09 –.02 .33 .38 11 15 Note. N = 100. Reliability estimates (Cronbach’s alpha) are in parentheses along the diagonal. Correlations greater than or equal to |.20|, p ≤ .05, correlations greater than or equal to |.27|, p ≤ .01. Ldr = leader; Conscientious = Conscientiousness; Em. Stability = Emotional Stability; Openness = Openness to Experience; Learning GO = Learning Goal Orientation; Prove GO = Performance-Prove Goal Orientation; Avoid GO = Performance-Avoid Goal Orientation; LSE = Leadership Self-Efficacy; AIMTL = Affective-Identity Motivation to Lead; Noncalculative Motivation to Lead; SNMTL = Social Normative Motivation to Lead. aWithin-group interrater agreement index (r wg(j)). 1. Ldr Agreeableness 4.04 2. Ldr Conscientious 3.58 3. Ldr Em. Stability 3.27 4. Ldr Extraversion 3.43 5. Ldr Openness 3.77 6. Ldr Learning GO 3.80 7. Ldr Prove GO 3.44 8. Ldr Avoid GO 2.85 9. Ldr LSE 4.13 10. Ldr AIMTL 3.56 11. Ldr NCMTL 4.01 12. Ldr SNMTL 3.49 13. Ldr Performance 2,465.13 14. Team Ratings 3.62 15. Team Profit 35,136.86 Variable TABLE 1 Descriptive Statistics and Intercorrelations Among Study Variables for Leaders Only 330 4.11 3.81 3.31 3.54 3.84 3.90 3.49 2.76 4.16 3.54 3.96 3.56 3.62 35,136.86 M 0.29 0.37 0.36 0.42 0.32 0.31 0.43 0.46 0.31 0.41 0.29 0.29 0.65 17,856.12 SD .15 .21 –.03 .10 .02 –.20 –.17 .06 –.27 .36 .08 .21 .17 1 .08 .11 .04 .25 .01 –.32 .32 .22 .17 .21 .02 –.01 2 .23 –.05 .06 –.28 –.20 –.11 –.20 .18 –.19 .04 .18 3 .11 .36 –.06 –.30 .35 .48 .09 .25 –.10 .00 4 .28 .13 –.06 .30 .29 .07 .17 –.05 –.01 5 .19 –.30 .40 .48 .42 .49 –.10 .08 6 .38 .19 .40 –.08 .35 –.22 –.02 7 –.25 –.16 –.21 .01 .07 .07 8 .64 .22 .36 .16 .01 9 .16 .44 .19 .05 10 .32 .06 .11 11 –.07 .04 12 13 .38 14 15 Note. N = 100 teams. Correlations greater than or equal to |.20|, p ≤ .05, correlations greater than or equal to |.27|, p ≤ .01. Em. Stability = Emotional Stability; Openness = Openness to Experience; Learning GO = LGO; Prove GO = Performance-Prove Goal Orientation; Avoid GO = Performance-Avoid Goal Orientation; LSE = Leadership Self-Efficacy; AIMTL = Affective-Identity Motivation to Lead; Noncalculative Motivation to Lead; SNMTL = Social Normative Motivation to Lead; Ldr = Leader. 1. Team Agreeableness 2. Team Conscientiousness 3. Team Em. Stability 4. Team Extraversion 5. Team Openness 6. Team Learning GO 7. Team Prove GO 8. Team Avoid GO 9. Team LSE 10. Team AIMTL 11. Team NCMTL 12. Team SNMTL 14. Team Ratings 15. Team Profit Variable TABLE 2 Descriptive Statistics and Intercorrelations Among Study Variables for Team Members (Aggregated) GOAL ORIENTATION AND LEADERSHIP 331 ference of the fit for the two models was statistically significant: ∆χ2(6, N = 400) = 922.90, p < .01. These results indicate that these constructs are also empirically distinct. The zero order correlations in Tables 1 and 2 reveal direct relationships between the individual differences examined and leadership effectiveness. Consistent with our hypotheses, none of the goal orientation dimensions have significant relationships with leadership effectiveness. Only leader extraversion, LSE, Affective-Identity MTL, and Noncalculative MTL had significant relationships with team member ratings of leadership effectiveness and the ratings were significantly related to team performance (team profit). Hypothesis 1 stated LGO would positively relate to LSE above and beyond the Big Five. We tested this hypothesis using hierarchical regression in which the five personality variables were entered in the first step and LGO was entered in the second step. Consistent with expectation, LGO was positively related to LSE; however, it did not account for a significant amount of variance above and beyond the personality variables (β = .19, p = .058; see Table 3). Consistent with Figure 1, LGO appears to partially mediate relationships between the Big Five and LSE, as the beta weights for the Big Five drop in the second step of the regression analyses. The second hypotheses posited the positive relationships between LGO and both Affective-Identity MTL and Social-Normative MTL are partially mediated by LSE. We conducted a very conservative test of this hypothesis by controlling for all of the Big Five variables before entering the independent variable for a given step, and we used Baron and Kenny’s (1986) approach and Sobel’s (1982) test to test for mediation. As shown in Table 4, the first regression for testing both Hypotheses 2a and 2b involved regressing LSE on LGO (after controlling for the Big Five), which is the same analysis we performed to test Hypothesis 1. In the second regression for Hypothesis 2a, Affective-Identity MTL was regressed onto LSE. This was significant (β = .60, p < .01) even after controlling for the Big Five. In the third regression, Affective-Identity MTL was regressed onto LGO. Again, incremental validity was shown above the Big Five (β = .21, p < .05). Finally, Affective-Identity MTL was simultaneously regressed onto LGO and LSE following the entry of the Big Five. Here the beta for LGO became nonsignificant (β = .10) providing preliminary evidence for partial mediation, supporting Hypothesis 2a. We further determined this change was significant using Goodman’s (1960) I version of Sobel’s (1982) test (z = 3.77, p < .01). We conducted the same analyses with Social-Normative MTL to test Hypothesis 2b. Both LSE (β = .47, p < .01) and LGO (β = .25, p < .05) were significantly related to Social-Normative MTL above and beyond the Big Five. As depicted in Table 4, when both variables were entered into the equation simultaneously, the beta weight for LGO became nonsignificant (β = .17), indicating partial mediation and support for Hypothesis 2b. Again, Sobel’s (1982) test indicated this change was 332 –.12 .27** .05 .26** .21* –.08 .23* .04 .21** .16 .18+ .11 .09 .08 .07 .10 .11 .09 .08 .07 .10 .09 SE B –.12 .31 .07 .35 .20 –.08 .26 .06 .29 .06 .19 .29 .32 .03+ R2 .29** R2 .09 .07 .07 .06 .08 .09 .08 .07 .06 .08 .07 .09 .07 .07 .06 .08 .06 .01 –.04 .16* .08 .13* .19* –.05 SE B –.04 .16* .09 .13* .19* –.04 .15* .09 .13* .18* B .01 –.05 .22 .12 .22 .22 –.07 –.05 .22 .14 .23 .22 –.05 .22 .14 .23 .22 Noncalculative MTL .01 .00 .23** R2 .23 .23 .23 R2 Note. The B weights in the columns are from the step of entry into the model. Ldr = leader; Prove Goal Orientation = Performance-Prove Goal Orientation; Avoid Goal Orientation = Performance-Avoid Goal Orientation; MTL = Motivation to Lead. +p ≤ .10. *p ≤ .05. **p ≤ .01. 1. Ldr Agreeableness Ldr Conscientiousness Ldr Emotional Stability Ldr Extraversion Ldr Openness 2. Ldr Agreeableness Ldr Conscientiousness Ldr Emotional Stability Ldr Extraversion Ldr Openness Ldr Learning Goal Orientation Ldr Prove Goal Orientation 2. Ldr Agreeableness Ldr Conscientiousness Ldr Emotional Stability Ldr Extraversion Ldr Openness Ldr Avoid Goal Orientation B Leadership Self-Efficacy TABLE 3 Incremental Validity of Goal Orientation on Leadership Self-Efficacy (Hypothesis 1) and Noncalculative MTL (Hypothesis 3) 333 –.27* .27** –.02 .34** .17* –.20* .10 –.06 .18** .04 .63** –.23* .23* –.03 .28** .11 .21* –.18 .09 –.06 .16* .02 .10 .61** .11 .10 .08 .07 .10 .09 .08 .07 .07 .09 .10 .11 .10 .08 .08 .11 .10 .09 .08 .07 .07 .09 .08 .10 SE B –.26 .30 –.03 .44 .15 –.19 .11 –.07 .23 .03 .60 –.22 .25 –.04 .37 .10 .21 –.17 .10 –.07 .20 .01 .10 .58 .26** .51** .29** .52** .25** .03* .26** R2 .26** R2 –.01 .14+ .09 .16** .15+ .04 .03 .06 .06 .06 .40** .03 .09 .08 .11+ .09 .20* .06 .01 .06 .03 .03 .14+ .37** B .09 .08 .07 .06 .09 .09 .07 .06 .06 .08 .08 .09 .08 .07 .06 .09 .08 .09 .07 .06 .06 .08 .08 .08 SE B –.01 .19 .13 .26 .16 .04 .04 .10 .10 .07 .47 .03 .13 .12 .18 .10 .25 .07 .01 .09 .05 .04 .17 .43 R2 .18** .05* .16** .21** Social-Normative MTL Note. N = 100. The B weights in the columns are from the step of entry into the model. Ldr = leader; MTL = Motivation to Lead. +p < .10. *p < .05. **p < .01. 1. Ldr Agreeableness Ldr Conscientiousness Ldr Emotional Stability Ldr Extraversion Ldr Openness 2. Ldr Agreeableness Ldr Conscientiousness Ldr Emotional Stability Ldr Extraversion Ldr Openness Ldr Leadership Self-efficacy 2. Ldr Agreeableness Ldr Conscientiousness Ldr Emotional Stability Ldr Extraversion Ldr Openness Ldr Learning Goal Orientation 2. Ldr Agreeableness Ldr Conscientiousness Ldr Emotional Stability Ldr Extraversion Ldr Openness Ldr Learning Goal Orientation Ldr Leadership Self-efficacy B Affective-Identity MTL TABLE 4 Mediating Role of Leadership Self-Efficacy on the Learning Goal Orientation-Motivation to Lead Relationships (Hypothesis 2) .39** .26** .37** .21** R2 334 HENDRICKS AND PAYNE significant (z = 3.44, p < .01), demonstrating further support for partial mediation. Consistent with Figure 1, the beta weights for the Big Five drop when LGO is added to the equation, suggesting LGO mediates relationships between the Big Five and Affective-Identity and Social-Normative MTL factors. Hypothesis 3 proposed that both PPGO and PAGO would negatively relate to Noncalculative MTL above and beyond the Big Five. Because the two PGO dimensions were significantly related to one another (r = .36), we calculated two separate regression equations. As depicted in Table 3, after controlling for the Big Five, neither PPGO nor PAGO accounted for a significant amount of variance in Noncalculative MTL (β = .01, ns and β = –.07, ns), indicating no support for Hypothesis 3a or 3b. Contrary to Figure 1, PPGO and PAGO do not appear to mediate relationships between the Big Five and Noncalculative MTL. The fourth hypothesis predicted significant positive relationships between the MTL factors and leadership effectiveness after controlling for both the leaders’ and team members’ Big Five personality characteristics, as well as the leader’s previous task performance. We tested this hypothesis with both indicators of leadership effectiveness: team ratings and team profit, separately. First, the leader’s performance on the task by him- or herself and the group members’ Big Five, followed by the leader’s Big Five, and then the leader’s three MTL factors were entered into a regression equation to predict each measure of leadership effectiveness (see Table 5). Consistent with expectation, Noncalculative MTL was significantly and positively related to team ratings (β = .23, p < .05); however, contrary to expectation, Social-Normative MTL related negatively (β = –.24, p < .10), not positively to the ratings. The relationships between Affective-Identity MTL and team ratings (β = .16, p < .10) as well as team profit (β = .11, p < .10) approached significance. Neither Noncalculative nor Social-Normative MTL related to the team profit criterion. These results provide some support for Hypotheses 4b. DISCUSSION The purpose of this study was to test an indirect relationship between goal orientation and leadership effectiveness through the more proximal individual difference characteristics LSE and MTL. We also test the incremental validity of these predictors over and above the Big Five personality characteristics. Consistent with our expectations and research by McCormick (1999), LGO was positively related to LSE, which in turn positively related to Affective-Identity MTL and Social-Normative MTL suggesting that individuals with a high level of LGO are more likely to want to lead because they like to lead and feel a sense of duty to lead. Contrary to expectation, PPGO and PAGO were not significantly related to Noncalculative MTL above and beyond the Big Five. This may have been a function of limited power to detect these relationships, because PAGO and 335 .00 .48* –.02 –.01 –.17 –.10 –.05 .09 –.03 .29** –.07 .18+ –.34+ .34* .00 .24 .18 .19 .16 .21 .15 .12 .11 .10 .14 .15 .18 .17 SE B .17 .21 –.01 .00 –.11 –.05 –.04 .08 –.04 .32 –.05 .16 –.24 .23 .09 .18+ .24 .09+ .06* R2 .09 R2 1.13** 9301.50 –2650.55 6639.82 –3069.77 559.47 –5675.35 1705.02 815.79 3226.62 –2906.10 3436.60 5914.68 –3785.43 B .34 6282.98 4678.04 5084.08 4289.25 5422.63 3961.26 3253.94 2952.32 2606.94 3782.79 4103.11 4796.80 4987.17 SE B .33 .15 –.06 .13 –.07 .01 –.17 .06 .03 .13 –.08 .11+ .14 –.10 Team Profit .02 .04 .16* R2 .21+ .20* .16* R2 Note. N = 100. The B weights in the columns are from the step of entry into the model. Stab = Stability; Exp = Experience; Ldr = leader; MTL = Motivation to Lead. +p < .10. *p < .05. **p < .01. 1. Leader Performance Team Agreeableness Team Conscientiousness Team Emotional Stab Team Extraversion Team Openness to Exp 2. Ldr Agreeableness Ldr Conscientiousness Ldr Emotional Stability Ldr Extraversion Ldr Openness to Exp 3. Ldr Affective-Identity MTL Ldr Social-Normative MTL Ldr Noncalculative MTL B Team Ratings TABLE 5 Incremental Validity of the Motivation to Lead Factors on Leadership Effectiveness (Hypothesis 4) 336 HENDRICKS AND PAYNE Noncalculative MTL were negatively correlated with one another. Thus, individuals with strong PAGO may be more likely to calculate the pros and cons of leading and therefore be less motivated to assume a leadership role. Although we did not propose specific hypotheses, our data provide some empirical support for LGO as a mediator of the Big Five/LSE, Big Five/Affective-Identity MTL, and Big Five/Social-Normative MTL relationships. Consistent with Figure 1, the Big Five personality characteristics appear to be more distal leadership traits influencing motivational mechanisms through achievement goal tendencies. Future research theorizing about and replicating these patterns of relationships seems warranted. We also examined the predictive validity of the MTL factors for leadership effectiveness. Consistent with Chan and Drasgow’s (2001) theoretical framework, Noncalculative MTL was positively related to team ratings of leadership effectiveness after controlling for the leader’s previous task performance and the leader and the team members’ Big Five characteristics, indicating that those who are motivated to lead because they do not calculate the costs of leading are more effective leaders in the eyes of their followers. Affective-Identity MTL also came very close to relating significantly to team ratings of leadership effectiveness and team profit. Larger sample sizes with more power to detect significant relationships may have yielded stronger support for these relationships. Contrary to theory, Social-Normative MTL was negatively related to team ratings of leadership effectiveness, indicating that those who are motivated to lead out of a sense of duty are actually perceived to be less effective. Similarly, Chan and Drasgow found that Social-Normative MTL did not account for unique variance in leadership potential ratings. Additional research is needed to confirm if Social-Normative MTL is not a sufficient type of motivation to facilitate leadership effectiveness or if it actually hinders leadership effectiveness. Examining profiles of the three MTL factors may illuminate these findings. Finally, we assessed team member traits, aggregated them to the team level, and examined how they influenced leadership effectiveness. It is interesting that only team member PPGO and Agreeableness related significantly to the leader effectiveness ratings. We did not examine whether leader and team member traits have interactive effects on leadership and team outcomes. The number of possible interactions is so extensive that further theorizing seems warranted before examining these relationships. Our research contributes to the individual difference and leadership literatures in four ways: 1. We supplement Chan and Drasgow’s (2001) theoretical framework with three additional individual difference variables and two measures of leadership effectiveness. GOAL ORIENTATION AND LEADERSHIP 337 2. We respond to Judge et al.’s (2002) call to examine why personality relates to leadership effectiveness by providing conceptual and empirical linkages between proximal and distal individual differences and leadership effectiveness. 3. We provide additional empirical evidence of the nomological network and validity for MTL. 4. We demonstrate the incremental validity of narrow leader traits over and above broad leader and team member traits. Theoretical Implications Our research has implications for theory in a number of domains to include individual differences, goal orientation, and leadership. First, by examining the incremental validity of goal orientation over and above the Big Five, we demonstrated the goal orientation dimensions are empirically distinct from broad personality constructs. We also demonstrate that other individual differences constructs besides the Big Five are important predictors of more proximal antecedents of leadership effectiveness. Although previous research had examined the influence of leadership variables on followers’ goal orientation (e.g., Dragoni, 2005; Gorenflo-Gilbert, 1999; Schwager, 1997), this is the first study to examine the leader’s goal orientation on leadership effectiveness. We added the mediating variables LSE and MTL to the list of goal orientation outcomes. More specifically, we provide additional support for the LGO-specific self-efficacy relationship. In this study, we examine LSE, which demonstrated a positive relationship with LGO, indicating that individuals with a high level of LGO tend to be more efficacious about their leadership abilities. We also demonstrated some support for the idea that individuals with high levels of PAGO are more calculative of the costs relative to the benefits of leading. In contrast, individuals with high levels of LGO were motivated to lead for affective-identity and social normative reasons. These findings provide further insight about these motivational orientations suggesting that they have implications for calculative thinking and beliefs. It would be interesting to see if these cognitions extend to nonleadership contexts as well. We utilized a three-dimensional measure of goal orientation and examined each dimension separately. Recent research by Elliot and colleagues (Conroy, Elliott, & Hofer, 2003; Elliot & McGregor, 2001) suggests that LGO may also have prove and avoid components and that profiles of goal orientation (e.g., Carr & DeShon, 2002) may be a more meaningful way to examine this construct, as the dimensions are not mutually exclusive. It might also prove fruitful to examine the relationship between the leader’s dispositional goal orientation and the team members’ state goal orientation to further our understanding of the role of the leader’s goal orientation in leadership contexts. For example, do leaders with a strong LGO foster a 338 HENDRICKS AND PAYNE high level of state LGO in their followers, which may in turn facilitate higher levels of collective efficacy? We contributed to the nomological network of MTL. First, we replicated Chan and Drasgow’s (2001) findings that the MTL factors are significantly related to but distinct from LSE. We also replicated relationships between the Big Five and the three MTL factors, as well as LSE. Consistent findings suggest robust relationships and warrant further theoretical attention. Second, we extend Chan and Drasgow’s research by examining the relationships between the MTL factors and leadership effectiveness, noting additional research on the relationship between Social-Normative MTL and leadership effectiveness seems warranted. The trait theory of leadership focuses on the leader’s traits as opposed to the team members’ traits. Yet leadership effectiveness is often operationalized as a team outcome that is also determined by variables beyond the leader’s control (e.g., the team member’s traits and skills). Although Chan and Drasgow’s (2001) framework illuminates why leader traits are likely to influence leader behavior, it does not extensively incorporate team inputs (e.g., team member’s traits) and processes (e.g., cohesion and communication) that are also known to contribute to team outcomes. We demonstrated proximal and distal leader traits predicted leadership effectiveness above and beyond team member traits. Another avenue for future research is to integrate Chan and Drasgow’s (2001) framework with models of team effectiveness (e.g., Gladstein, 1984), perhaps by including aspects of functional leadership theory (Hackman & Walton, 1986). Because Chan and Drasgow’s framework focuses on leader behavior, how leader traits and MTL influence team performance is not fully explicated. According to their framework, MTL leads to participation in leadership roles and training, which leads to social knowledge and skills for leading and leadership style, which in turn leads to leadership performance. We believe leadership knowledge and skills contribute to appropriate leadership behaviors, which in turn facilitate effective team processes (e.g., communication). According to functional leadership theory, leaders demonstrate two basic categories of behaviors: (a) developing and shaping team processes and (b) monitoring and managing team performance (Hackman & Walton, 1986). One way they do this is establish and maintain a favorable team climate (Kozlowski & Doherty, 1989). Leaders with a strong LGO may encourage team members to develop new skills, set learning goals for the team, and provide feedback that promotes collective efficacy (Kozlowski, Gully, McHugh, Salas, & Cannon-Bowers, 1996). Practical Implications The study presented here offers some information that is likely to be useful when predicting successful leadership with simple assessments of individual differ- GOAL ORIENTATION AND LEADERSHIP 339 ences. Ideally, any organization should seek to identify those who may be more adaptable to assuming and carrying out leadership roles effectively for selection, placement, and promotion decisions. If organizations are going to expend resources to develop these individuals, then being able to predict who is more likely to be a successful leader with relatively inexpensive materials (e.g., self-report measures) would be highly util. This research also has practical implications for training leaders. For example, the development of leaders may be more efficient if the Big Five, goal orientation, LSE, and MTL are taken into account when selecting who receives leadership training or a developmental intervention. Individuals with high levels of Extraversion, Conscientiousness, Openness to Experience, LGO, MTL, LSE, and low levels of PPGO and PAGO may benefit the most from leadership training. This research suggests using a Big Five measure in conjunction with a goal orientation measure is more useful than using a Big Five measure alone. Finally, leadership trainers should strive to enhance leaders’ LSE and MTL during training as LSE and MTL are arguably more malleable than goal orientation and personality. Limitations and Directions for Future Research We acknowledge the limitations of our study. These are primarily weaknesses commonly associated with the characteristics of the sample and the use of a lab task. The sample was relatively homogeneous, consisting mostly of White 18- to 20-year-olds. We also assigned leaders instead of examining those who were nominated or emerged. Whereas the laboratory study allowed us to examine a large number of leaders in a standardized environment, the short time frame may not have been long enough for leaders to demonstrate all manifested behaviors and for all leadership and group processes to occur. At the same time, simulations are not considered entirely weak methods for studying leadership (e.g., Bass, 1990; Thornton & Cleveland, 1990), and the relationships we found are supported by theory. Additional tests of these relationships in the field are encouraged. Whereas our research provides some empirical support for LSE and MTL as mediators of the leader trait-leader effectiveness relationships, we did not examine the implied mediator leader behavior, and clearly there are more processes that are likely to occur between traits and outcomes that explain these relationships. For example, Lee, Sheldon, and Turban (2003) recently showed that goal level mediates relationships between goal orientation and performance. In team context, there are also group processes like communication and cohesion that are likely to mediate relationships between leader behaviors and leadership effectiveness. Ideally a test of Chan and Drasgow’s model would include all constructs depicted in their model. For example, we did not include values or interests or some potential moderators like situational factors in this study. An even more robust test of the model would include collecting longitudinal data to test the predictions 340 HENDRICKS AND PAYNE made for leaders’ development including their leadership experience and their acquisition of the knowledge and skills needed to be an effective leader. Future research should attempt to provide a comprehensive test of their model. Despite the limitations, we feel the goals of our study were met. The research reported herein developed a conceptual link between dispositional goal orientation and specific motivational consequences within the leadership domain. Subsequently, these hypothesized relationships were tested and some were supported, adding empirical support to the conceptual arguments. Finally, we shed some light on why leader traits influence leadership effectiveness, by proposing LSE and MTL as motivational mechanisms. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This paper is based on the first author’s Master’s thesis under the direction of Stephanie C. Payne. The authors wish to acknowledge the other thesis committee members, Charlie Samuelson and Christine Townsend. We also express our appreciation to Tome Kane for his assistance with task materials and measures and to Jennifer Camp, Melissa Frommert, Tracy Huffman, Thomas Lopez, Lee McGilvray, Taikia Smith, Catherine Vo, and Meredith Vrba for their assistance with data collection. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 17th annual Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology Conference, Toronto, Canada, April 2002. REFERENCES Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of self-control. New York: Freeman. Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182. Bass, B. M. (1990). Bass and Stogdill’s handbook of leadership: Theory, research, and managerial applications (3rd ed.). New York: Free Press. Bell, B. S., & Kozlowski, S. W. J. (2002). Goal orientation and ability: Interactive effects on self-efficacy, performance, and knowledge. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 497–505. Bliese, P. D. (2000). Within-group agreement, non-independence, and reliability: Implications for data aggregation and analysis. In K. J. Klein & S. J. Kozlowski (Eds.), Multilevel theory, research, and methods in organizations. (pp. 349–381). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Brett, J. F., & VandeWalle, D. (1999). Goal orientation and goal content as predictors of performance in a training program. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84, 863–873. Button, S. B., Mathieu, J. E., & Zajac, D. M. (1996). Goal orientation in organizational research: A conceptual and empirical foundation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 67, 26–48. Carr, J. Z., & DeShon, R. P. (2002). Empirical validation of a process model of goal orientation. In V. J. Fortunato (Chair), An examination of the motivational consequences of goal orientation. Sympo- GOAL ORIENTATION AND LEADERSHIP 341 sium conducted at the 17th annual meeting of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology Conference, Toronto, Canada. Chan, K., & Drasgow, F. (2001). Toward a theory of individual differences and leadership: Understanding the motivation to lead. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 481–498. Clore, G. L., Schwarz, N., & Conway, M. (1994). Affective causes and consequences of social information process. In R. S. Wyer, Jr., & T. K. Srull (Eds.), Handbook of social cognition (Vol. 1: Basic processes; Vol. 2: Applications; 2nd ed., pp. 323–417). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Conroy, D. E., Elliot, A. J., & Hofer, S. M. (2003). A 2 × 2 Achievement Goals Questionnaire for Sport: Evidence for factorial invariance, temporal stability, and external validity. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 25, 456–476. Devine, D. J. (2002). A review and integration of classification systems relevant to teams in organizations. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 6, 291–310. Dragoni, L. (2005) Understanding the emergence of state goal orientation in organizational work groups: The role of leadership and multilevel climate perceptions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 1084–1095. Dweck, C. S. (1986). Motivational processes affecting learning. American Psychologist, 41, 1040–1048. Dweck, C. S., & Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95, 256–273. Elliot, A. J., & Harackewitz, J. M. (1996). Approach and avoidance goal and intrinsic motivation: A mediational analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 461–475. Elliot, A. J., & McGregor, H. A. (2001). A 2 × 2 achievement goal framework. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80, 501–519. Elliott, E. S., & Dweck, C. S. (1988). Goals: An approach to motivation and achievement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 5–12. Farr, J. L., Hofmann, D. A., & Ringenbach, K. L. (1993). Goal orientation and action control theory: Implications for industrial and organizational psychology. In C. L. Cooper & I. T. Robertson (Eds.), International review of industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 193–232). New York: Wiley. Feasel, K. E. (1995). Mediating the relation between goals and subjective well-being: Global and domain-specific variants of self-efficacy. Unpublished master’s thesis, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Forgas, J. P. (1995). Mood and judgment: The affect infusion model (AIM). Psychological Bulletin, 117, 39–66. Gladstein, D. L. (1984). Groups in context: A model of task group effectiveness. Administrative Science Quarterly, 29, 499–517. Goldberg, L. R. (1990). An alternative “description of personality”: The Big-Five factor structure. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 54, 1216–1229. Goodman, L. A. (1960). On the exact variance of product. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 55, 708–713. Gorenflo-Gilbert, M. (1999). The effects of implicit theories of leadership ability on goal orientation, attributional processes, and learning outcomes. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, The City University of New York, Baruch. Hackman, J. R. (Ed.). (1990). Groups that work (and those that don’t): Creating conditions for effective teamwork. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Hackman, J. R., & Walton, R. E. (1986). Leading groups in organizations. In P. S. Goodman & Associates (Eds.), Designing effective work groups (pp. 72–119). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. House, R. J., & Aditya, R. N. (1997). The social scientific study of leadership: Quo vadis? Journal of Management, 23, 409–473. 342 HENDRICKS AND PAYNE House, R. J., & Podsakoff, P. M. (1994). Leadership effectiveness: Past perspectives and future directions for research. In J. Greenberg (Ed.), Organizational behavior: The state of the science (pp. 45–82). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Isen, A. M. (1987). Positive affect, cognitive processes, and social behavior. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 20, pp. 203–253). San Diego, CA: Academic. James, L. R., Demaree, R. G., & Wolf, G. (1984). Estimating within-group interrater reliability with and without response bias. Journal of Applied Psychology, 69, 85–98. Judge, T. A., Bono, J. E., Ilies, R., & Werner, M. (2002). Personality and leadership: A qualitative and quantitative review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 765–780. Kane, T. D. (1999). An examination of the leader’s regulation of groups. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. George Mason University, Fairfax, VA. Kane, T. D., Zaccaro, S. J., Tremble, T. R., & Masuda, A. D. (2002). An examination of the leader’s regulation of groups. Small Group Research, 33, 65–120. Kozlowski, S. W. J., & Doherty, M. L. (1989). Integration of climate and leadership: Examination of a neglected issue. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74, 546–553. Kozlowski, S. W. J., Gully, S. M., Brown, K. G., Salas, E., Smith, E. M., & Nason, E. R. (2001). Effects of training goals and goal orientation traits on multidimensional training outcomes and performance adaptability. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 85, 1–31. Kozlowski, S. W. J., Gully, S. M., McHugh, P. P., Salas, E., & Cannon-Bowers, J. A. (1996). A dynamic theory of leadership and team effectiveness: Developmental and task contingent leader roles. Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management, 14, 253–305. Langston, C. A., & Sykes, W. E. (1997). Beliefs and the Big Five: Cognitive bases of broad individual differences in personality. Journal of Research in Personality, 31, 141–165. Lee, F. K., Sheldon, K. M., & Turban, D. B. (2003). Personality and the goal-striving process: The influence of achievement goal patterns, goal level, and mental focus on performance and enjoyment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 256–265. LePine, J. A., Hollenbeck, J. R., Ilgen, J. R., & Hedlund, J. (1997). Effects of individual differences on the performance of hierarchical decision-making teams: Much more than g. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82, 803–811. Lord, R. G., DeVader, C. L., & Alliger, G. M. (1986). A meta-analysis of the relation between personality traits and leadership perceptions: An application of validity generalization procedures. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71, 402–410. Lord, R. G., & Hall, R. J. (1992). Contemporary views of leadership and individual differences. Leadership Quarterly, 3, 137–157. Markus, H. (1977). Self schemata and processing information about the self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 35, 63–78. McCormick, M. J. (1999). The influence of goal-orientation and sex-role identity on the development of leadership self-efficacy during a training intervention. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Texas A&M University, College Station. McGrath, J. E. (1984). Groups: Interaction and performance. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Payne, S. C., Youngcourt, S. S., & Beaubien, J. M. (2007). A meta-analytic examination of the goal orientation nomological net. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 128–150. Phillips, J. M., & Gully, S. M. (1997). Role of goal orientation, ability, need for achievement, and locus of control in the self-efficacy and goal-setting process. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82, 792–802. Piccolo, R., & Judge, T. (2006). What makes a “great” leader? Refining the personality-leadership relationship. Discussant comments on symposium at the 21st annual meeting of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology Conference, Dallas, TX. Saucier, G. (1994). Mini-markers: A brief version of Goldberg’s unipolar big-five markers. Journal of Personality Assessment, 63, 506–516. GOAL ORIENTATION AND LEADERSHIP 343 Schwager, E. H. (1997). The effects of implicit theories of leadership ability and superleadership on follower motivation and performance attributions. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, The City University of New York, Baruch. Sobel, M. E. (1982). Asymptotic intervals for indirect effects in structural equations models. In S. Leinhart (Ed.), Sociological methodology 1982 (pp. 290–312). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Stajkovic, A. D., & Luthans, F. (1998). Self–efficacy and work-related performance: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 124, 240–261. Steiner, I. D. (1972). Group process and productivity. New York: Academic. Thornton, G. C., & Cleveland, J. N. (1990). Developing managerial talent through simulation. American Psychologist, 45, 190–199. VandeWalle, D. (1997). Development and validation of a work domain goal orientation instrument. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 57, 995–1015. Yukl, G. (1989). Managerial leadership: A review of theory and research. Journal of Management, 15, 251–289. Yukl, G. (1998). Leadership in organizations (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Yukl, G., & Van Fleet, D. D. (1992). Theory and research on leadership in organizations. In M. D. Dunnette & L. M. Hough (Eds.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (2nd ed., Vol. 3, pp. 147–197). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. Zaccaro, S. J., Foti, R. J., & Kenny, D. A. (1991). Self-monitoring and trait-based variance in leadership: An investigation of leader flexibility across multiple group situations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76, 308–315.