Shoulder Comprehensive - WVU School of Medicine

advertisement

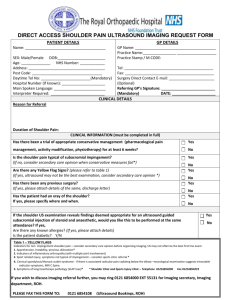

Shoulder Pain: Evaluation and Management Gaetano P. Monteleone, Jr., M.D. Dept. of Family Medicine West Virginia University School of Medicine monteleoneg@rcbhsc.wvu.edu www.thesportsmedicinecenter.com I. The Shoulder A. Anatomy Muscles/tendons-rotator cuff (supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, subscapularis), biceps, triceps, deltoid, serratus anterior, latissimus dorsi, pectoralis major and minor, trapezium. Ligaments- inferior, middle, and superior glenohumeral ligaments (the capsule); coracoacromial ligament, coracoclavicular ligament, acromioclavicular ligament. Bursa- subacromial, inferior scapular. Bones- humerus, scapula, clavicle. Joints- glenohumeral, sternoclavicular, acromioclavicular, "scapulothoracic". Cartilage- glenoid cartilage, labrum (fibrocartilage). Nerves- brachial plexus. Vascular- subclavian, axillary, and brachial arteries and veins. B. Biomechanics 1. Capsule The capsule creates the glenohumeral joint space. There are four ligaments that are really just thickenings of the capsule. These thickenings, however, have individual functions in the stability of the glenohumeral joint. Relative to the hip and the acetabulum, the glenohumeral joint allows for more motion and, therefore, results in less stability. The capsule: Superior glenohumeral ligament Middle glenohumeral ligament Inferior glenohumeral ligament complex Coracohumeral ligament 2. The structures that create stability at rest are different than those that stabilize during motion. The static stabilizers include the capsule, GH ligaments and the fibrocartilaginous labrum. The dynamic stabilizers of the shoulder include the rotator cuff (RC) musculature, long head of the biceps, and the scapular rotators (serratus anterior, rhomboids and levator scapulae). 3. The surface of the humeral head has been reported to be 2-4 times that of the glenoid. As a result, only 25-30% of the humeral head is in contact with the glenoid fossa. The Shoulder Pain: Evaluation and Management Gaetano P. Monteleone, Jr., M.D. Dept. of Family Medicine West Virginia University School of Medicine monteleoneg@rcbhsc.wvu.edu www.thesportsmedicinecenter.com fibrous, meniscus-like glenoid labrum increases the congruity between the two structures. The tendon of the long head of the biceps inserts in the superior portion of the labrum. The inferior glenohumeral ligament complex attaches to the inferior portion of the labrum. Vascularity is limited to the peripheral region of the labrum, and like the meniscus of the knee, decreases with advancing age. The average depth of the glenoid is doubled from 2.5 to 5.0 mm by the labrum. C. History 1. Chief Complaint -Dislocation -Subluxation -Apprehension -Pain -Weakness 2.Age- Younger age favors instability, with the ligamentous structures tightening with aging. As the patient ages, there is increasing chance for tendinitis, bursitis and degenerative changes of the acromion (spurring) leading to subacromial impingement or RC tear. 3. Arm Dominance- assess effects on job and sport. 4. Occupation/Sport/Activities- overhead activities such as house painting, carpentry, volleyball, baseball, tennis, etc. may lead to RC tendinitis, bursitis and impingement. 5. Mechanism of Injury- external rotation with abduction or hyperextension favors instability, while overhead activities (brushing hair, jars/cans in cupboard) cause symptoms of impingement. In addition, note any history of paresis or paresthesias (dead arm syndrome) which can be seen in instability. 6. Current and Previous Treatment- information regarding the duration of dislocation, duration of symptoms, whether reduction was required, duration of immobilization, rehabilitation, medicines (NSAID's/narcotics), etc. 7. Recurrences?- frequency, activity during recurrences, voluntary/involuntary, and treatment. D. Physical Exam A careful physical exam must be performed both to confirm the suspected diagnosis and to rule out any other causes of symptoms (such as cervical radiculopathy). Thus a complete exam must include examination of the cervical spine and the entire upper extremity not just the glenohumeral joint. It is essential to examine both sides to serve as a basis of comparison. 1. Inspection Attitude Muscle features - tone/atrophy/hypertrophy of dominant side Bony deformity - AC joint, SC joint Erythema Skin manifestations/ecchymosis Shoulder Pain: Evaluation and Management Gaetano P. Monteleone, Jr., M.D. Dept. of Family Medicine West Virginia University School of Medicine monteleoneg@rcbhsc.wvu.edu www.thesportsmedicinecenter.com • 2. Palpation Local tenderness Edema Temperature changes Deformities Muscle characteristics - tone, consistency 3. Joint Motion Glenohumeral:scapulothoracic normal 2:1 Range of motion a. Active-thrower may have natural asymmetry b. Passive 4. Manual Muscle Testing Abduction 0-180°; deltoid, supraspinatus Adduction 0-45°; pectoralis major, latissimus dorsi Forward flexion 0-180°; anterior deltoid Extension 0-60°; posterior deltoid External Rotation 0-90°; infraspinatus, teres minor Internal Rotation 0-70°; subscapularis 5. Special Tests Impingement Signs/Test a. Neer's impingement sign - positive if maximum passive forward flexion/internal rotation causes pain in last 10-15° of motion arc - thought to be due to supraspinatus tendon being impinged against anterior inferior acromion b. Hawkin's impingement sign - humerus forward flexed to 90° (with elbow flexed to 90°) then actively internally rotate shoulder. Positive test is pain. c. Impingement injection test - response to subacromial injection of lidocaine 2% - regarded as positive if >50% reduction or abolition of impingement signs d. Biceps Evaluation ¾ Yergason’s Test - active resisted supination with the elbow flexed to 90° and forearm fully pronated - positive if elicits pain at bicipital groove ¾ Speed’s Test * more sensitive than Yergason’s - humerus forward flexed to ~ 60°, resisted elevation of arm with Shoulder Pain: Evaluation and Management Gaetano P. Monteleone, Jr., M.D. Dept. of Family Medicine West Virginia University School of Medicine monteleoneg@rcbhsc.wvu.edu www.thesportsmedicinecenter.com the elbow fully extended and forearm fully supinated - positive if elicits pain at bicipital groove - considered more accurate test for biceps tendinitis • Instability Tests - examine both sides, asymptomatic side first - examine in both the upright and supine positions - document amount of glenohumeral translation - attempt to reproduce symptoms of subluxation/apprehension a. Apprehension test - performed both upright and supine - arm abducted to 90°, externally rotated, anterior translation stress applied to humeral head - positive if produces “apprehension” b. Relocation Test - generally attributed to Jobe - perform apprehension test to elicit anterior apprehension - at point of apprehension, apply posteriorly directed force to prevent anterior translation of humeral head. Positive test produces abolition of apprehension and pain with posteriorly-directed force c. Load/Shift test - perform upright with arm at side and supine with arm at 20°-30° abduction and 90° abduction - humeral head is “loaded” to ensure centering on the glenoid fossa - anterior/posterior translational directional stress forces applied in attempt to “shift” humeral head - grade as trace, 1+, 2+, 3+ (Fig. I) according to degree of translation d. Andrew's modified-Lachman test of the shoulder - with patient in supine position, examiner places one hand behind proximal humerus while gently grasping the elbow at the bicondylar axis at the elbow. Patient's humerus is abducted approximately 120°. With the elbow held steady the examiner gently translocates the humeral head anteriorly, evaluating for amount of excursion and quality of end point. -shoulder with anterior instability may show increase in laxity and difference in end point quality compared to unaffected side - patient must be completely relaxed e. Labral "clunk" test - same position as the test in 'd'. The examining hand behind the humeral Shoulder Pain: Evaluation and Management Gaetano P. Monteleone, Jr., M.D. Dept. of Family Medicine West Virginia University School of Medicine monteleoneg@rcbhsc.wvu.edu www.thesportsmedicinecenter.com head palpates for a "clunk" as the other hand moves the humerus in a rotary motion, in effect trying to trap the labral tear between the humeral head and glenoid. This is analogous to the McMurray's test for meniscal tears of the knee. f. Sulcus sign - patient seated with arms at side - downward traction force applied to adducted arm (arm at side) - space or distance between lateral acromion and humeral head noted - graded 1+ (< 1 cm), 2+ (1-2 cm), 3+ (> 2 cm) - indicative of inferior instability - pathognomonic of multidirectional instability 6. Generalized ligamentous laxity- if laxity is evident at the GH joint, assess for laxity in other common areas: a. Thumb hyperabduction - “thumb-to-wrist” test b. Index MCP hyperextension c. Elbow recurvatum d. Knee recurvatum 7. Neurovascular Assessment a. C5-T1 neuro exam: sensory, motor, reflex b. Adson’s maneuver- arm abducted to 60°, in slight extension, external rotation; full extension at elbow. Examiner palpates radial pulse. Pt then rotates head to side of arm being examined. Positive test is dramatic diminution or ablation of pulse. c. Wright's maneuver- similar to above, except 90° flexion at elbow. Positive test is change in pulse as above. d. Roos maneuver- Pt abducts shoulders to 90°, elbows flexed to 90°, externally rotates to 90°. The pt then opens and closes his/her hands repetitively for up to 3 minutes. A positive test reproduces the pt's pain, paresthesias. N.B. Thoracic outlet syndrome will produce positive tests in b-d. E. Diagnostic testing 1. Plain radiography The indicated studies will depend on the clinical situation. In the acute dislocation, the radiographs should provide information regarding the direction of dislocation, presence of associated bony lesions (Bankart, Hill-Sachs, reverse Hill-Sachs), and presence of acute fracture of the proximal humerus. “Trauma series” • true AP view (in the plane of the scapula) Shoulder Pain: Evaluation and Management Gaetano P. Monteleone, Jr., M.D. Dept. of Family Medicine West Virginia University School of Medicine monteleoneg@rcbhsc.wvu.edu www.thesportsmedicinecenter.com • scapular lateral “Y” view • axillary lateral view (West Point view) These three views are all at 90° to one another thus maximizing the information. In addition, the positioning of the patient for the above views requires minimal glenohumeral motion and, therefore, minimizes pain for the acutely injured patient. “Instability series” • AP views with the humerus in internal and external rotation (IR and ER) • West Point (axillary lateral) view • Stryker notch view "Impingement series" • AP with IR and in ER views • West Point view • Supraspinatus outlet view (Alexander) • • • • • • • a. AnteroPosterior (AP) views (see figure at right) • important to differentiate between AP of shoulder and AP of GH joint (also known as the AP of the scapula) scapular AP view is the true AP view of GH joint AP with IR of humerus will reveal Hill-Sachs lesion in 92% of cases. Humerus looks like a "light bulb" AP with ER of humerus will visualize humeral neck in profile tuberosities b. Scapular Lateral or “Y” view may be helpful in acute dislocation since minimal motion required helpful in determining anterior/posterior relationship of humerus to glenoid not define fractures of glenoid Shoulder Pain: Evaluation and Management Gaetano P. Monteleone, Jr., M.D. Dept. of Family Medicine West Virginia University School of Medicine monteleoneg@rcbhsc.wvu.edu www.thesportsmedicinecenter.com • • c. West Point axillary lateral view provides excellent visualization of glenoid and humeral head (Bankart and Hill-Sachs lesions, respectively. delineates the spatial relationship of the two structures thus best for determining direction of dislocation (see figure at right). • d. Stryker Notch view most sensitive technique for detection of Hill-Sachs defect • e. Supraspinatus outlet (Alexander) view helpful for visualizing subacromial spurs which may contribute to RC pathology and shoulder impingement 2. Arthrography Double contrast arthrography has been demonstrated to be useful in detecting rotator cuff tears, biceps tendon abnormalities, adhesive capsulitis, and glenoid labral lesions. Its use has generally been supplanted by MRI. Some medical centers use an MRI-arthrogram to assess labral integrity. 3. CT Arthrography Double contrast CT-arthrography remains helpful for the detection of capsulolabral lesions associated with anterior instability, however its use has been supplanted by the MRI. Still its sensitivity and specificity in detecting and characterizing glenohumeral pathology have been reported as high as 100% in studies correlating surgical findings. It also enables detection of large capsular spaces in instability. Drawbacks include invasiveness, administration of contrast, and possible complications (anaphylaxis, infx). 4. Magnetic Resonance Imaging The use of MRI in the evaluation of shoulder pathology has become increasingly more common and widespread. Many recent studies have demonstrated the high sensitivity and specificity of MRI in the assessment of labral lesions (sensitivity 90100%, specificity 70-100%). The use of MRI in impingement diagnoses is helpful when assessing the integrity of the RC tendons and the subacromial space. However, high interobserver and intraobserver variability has been reported as compared to other modalities. In addition, MRI continues to entail high cost. MRI may be enhanced with Shoulder Pain: Evaluation and Management Gaetano P. Monteleone, Jr., M.D. Dept. of Family Medicine West Virginia University School of Medicine monteleoneg@rcbhsc.wvu.edu www.thesportsmedicinecenter.com intra-articular injection of contrast, known as MR-arthrogram. This helps to visualize the glenoid labrum, a structure at risk in pts with instability. D. Specific Injuries 1. Rotator Cuff Tendinitis/Impingement The RC tendons may become inflamed with overuse in the weekend warrior. The tendons can become so inflamed they may be encroached upon when glenohumeral joint moved (ie: abducted, forward flexion, etc.). This encroachment may be due to: • • • Bone- acromion (shape of acromion, existence of spurs, etc.) Instability (secondary impingement due to increased joint motion, especially pediatric pts) Rotator cuff tendinitis, bursitis (swollen, thickened tendons decrease usable space in the supraspinatus outlet) The following is a schema regarding the histopathology of tendinitis and impingement as related to age proposed by Neer: Neer Classification Histopathology Age (Years) Stage I Tendon with edema, hemorrhage and inflammation. < 25 Stage II Tendon fibrosis, scar and fiber dissociation; thickened bursa. 25-40 Stage III Bony alteration of the acromion and tuberosity, tendon rupture. > 40 • • • • • a. History Pain with overhead activity Lack of trauma Age over 35 More insidious onset Sometimes weakness (secondary to pain), not true neuromyopathic weakness • • • • b. Physical Exam + pain to palpation in a variety of areas + pain with manual muscle testing of RC, biceps + impingement signs (Neer's, Hawkin's signs), impingement injection test Full ROM (lack of full ROM requires ruling out adhesive capsulitis vs RC tear) - instability testing (unless impingement secondary to instability in young) Shoulder Pain: Evaluation and Management Gaetano P. Monteleone, Jr., M.D. Dept. of Family Medicine West Virginia University School of Medicine monteleoneg@rcbhsc.wvu.edu www.thesportsmedicinecenter.com c. Radiology Recall that the impingement series includes the AP with IR and ER, West Point views. Some authors include the supraspinatus outlet view (Alexander view) to assess the shape of the acromion and for subacromial spurs. Bigliani evaluated acromial shape and reported that the acromion can be flat (Type 1), curved (Type 2) and beaked/with a spur (Type 3). See figure below. He noted that there was a higher incidence of rotator cuff tears in type 3 acromion. d. Treatment • Rehab = RC and scapular stabilizer strengthening • Cryotherapy • NSAID's • ? Steroid injection: if no concern for RC tear or labral tear. • Consider REFERRAL for surgery for recalcitrant pain or large subacromial spur/type 3 acromion. e. Monitoring Recheck patient for improvements in pain, activities of daily living, work-related function. If anti-inflammatory regimen, rehab, etc. does not significantly improve symptoms, reconsider the diagnosis. AC joint abnormalities can present similarly to impingement. Consider tumors, as well. Consider REFERRAL for recalcitrant sxs. Removal of the bursa, shaving the inferior acromion, creating a larger supraspinatus outlet may decrease symptoms. At the end of the handout are examples of rotator cuff strengthening exercises and range of motion exercises to utilize with most patients. These come courtesy of Tools RG Exercise Xpress software from the Saunders Co. Small weights may be a substitute for the theraband material. 2. Rotator Cuff Tear Full thickness disruption of the tendon. Most common is the supraspinatus tendon at insertion into the greater tuberosity. Occurs mostly in patients greater than 40 yrs. Hx- mechanism = Indirect force on an abducted arm. Symptoms include acute pain and weakness after a traumatic event. Remember, if the patient has had chronic irritation of the tendons (overuse, spur), the trauma need not be high velocity. PE- may have painful arc from 70-120° abduction. Patients with a large tear may not be able to abduct past 90°. The examiner will still be able to passively abduct fully (NOTE: therefore PROM > AROM!). There may be a positive drop arm test with large tears. If initially undiagnosed, there may be atrophy of supraspinatus and infraspinatus. Shoulder Pain: Evaluation and Management Gaetano P. Monteleone, Jr., M.D. Dept. of Family Medicine West Virginia University School of Medicine monteleoneg@rcbhsc.wvu.edu www.thesportsmedicinecenter.com Dx- Mainly H&P. Xrays may demonstrate a type 3 acromion (figure below, C). Rarely necessary to make the diagnosis, an MRI will demonstrate these tears readily. Differential diagnosis includes nerve entrapment, adhesive capsulitis, RC impingement. Rx- aggressive P.T. similar to that of RC tendinitis. NSAID's may benefit acutely. Avoid steroids, since altered healing potential is possible. If rehab fails to increase ROM, decrease pain consider surgical repair. Consider surgical options more quickly in young athletes. from Bigliani LU, et al. Orthop Trans. 10:228, 1986. 3. Adhesive Capsulitis- also known as "frozen shoulder" or calcific tendinitis. The RC tendons no longer function to mobilize the shoulder. Hx- Progressive loss of ROM with accompanying pain. There may or may not be antecedent trauma. Pts with impingement or RC tear can progress to this. PE- the normal Glenohumeral:Scapulothoracic (GH:ST) ratio is changed. The normal GH:ST is 2:1. As the shoulder abducts from 0-180°, the humeral head contributes 2° for every 1° of scapular motion. With adhesive capsulitis, there is decreased glenohumeral motion, so that the GH:ST may be 1:1, or even 1:2. The pt will try to raise his/her arm by side-bending their thoracic spine. There is lack of active abduction, and passive abduction. The lack of BOTH active and passive abduction distinguishes adhesive capsulitis from RC tear. Remember, with RC tear, the examiner will still be able to passively abduct the pts shoulder. Dx- H&P. Xrays may demonstrate degenerative changes and calcifications. In addition, xrays will demonstrate other causes of decreased ROM (fractures, loose bodies, etc.). Rx- aggressive PT to improve ROM and strength is mainstay of rx. Mobilization is key! Steroid injections have been recommended if PT fails. REFERRAL to orthopedics of cases that do not respond to PT. May require manipulation under anesthesia. • In addition, PREVENTION of this can occur if aggressive mobilization as treatment of RC tears and impingement. The natural inclination of pts with pain is to limit motion. Proper education and abundant use of home exercise programs with ROM and theraband exercises may help to prevent. Further, adequate follow-up is required to encourage maintenance Shoulder Pain: Evaluation and Management Gaetano P. Monteleone, Jr., M.D. Dept. of Family Medicine West Virginia University School of Medicine monteleoneg@rcbhsc.wvu.edu www.thesportsmedicinecenter.com of exercise programs. 4. Biceps tendon rupture I am including this injury in this lecture since biceps rupture may be the result of chronic inflammation as well as a traumatic rupture. Two main types: proximal (more common) and distal ruptures. Rarely, short head of the biceps may rupture. One series demonstrated 96% proximal (long head) ruptures, 1% proximal (short head) ruptures, 3% distal ruptures. a. Proximal biceps ruptures: involve the long head of the biceps that inserts into the inferior portion of the glenoid rim. Remember, the short head of the biceps inserts into the coracoid process. Generally involves resistance to active flexion of the elbow. The tear often occurs at the biceps groove, but can occur at the site of insertion-with or without avulsion fracture of the glenoid rim. Hx- pain in the biceps. May have a history of biceps tendinitis associated with impingement. Pain with flexion activities of the elbow and supination at the forearm. PE- classic finding of retracted and “balled up” muscle belly giving the Popeye appearance to the muscle (compare to unaffected side). May also see ecchymosis at the site. There is generally some weakness to flexion at the elbow, though not nearly as severe as with distal ruptures. Recall that with proximal ruptures, the patient still has functional short head of the muscle. Dx- usually based on H&P. Xray usually negative; occasionally + for avulsion fracture. If uncertain, MRI will demonstrate this abnormality nicely. Rx- supportive care is necessary (PRICES). PT may be helpful. Generally, not a longstanding problem unless this occurs in a bodybuilder, where the look of the muscle matters. There will always be the Popeye look to the muscle. b. Distal biceps ruptures: involve the distal tendon rupture from its insertion into the radial tuberosity. Typically occurs in men during fourth through sixth decades of life (with a large range from 20-70 yrs). Pre-existing degenerative changes of the tendon appears to be a risk factor for rupture. Hx- acute onset of pain, ecchymosis, edema during resisted flexion. In fact most distal ruptures occur during eccentric contraction of this tendon- meaning exercise involving elongation of the tendon, such as the “down phase” of doing a curl. PE- ecchymosis, edema, pain to palpation at the antecubital fossa. Significant weakness to elbow flexion and forearm supination. Dx- mostly on H&P. Xray typically normal but may demonstrate avulsion fracture at the radial tuberosity. Rx- While results are conflicting, but most authors suggest early surgical treatment. Nonsurgical treatment has been recommended by some- there appears to be significant loss of extension and flexion with resultant weakness. Shoulder Pain: Evaluation and Management Gaetano P. Monteleone, Jr., M.D. Dept. of Family Medicine West Virginia University School of Medicine monteleoneg@rcbhsc.wvu.edu www.thesportsmedicinecenter.com 5. Osteolysis of the Clavicle Degenerative condition of the distal end of the clavicle. Common with repetitive arm motion with the humerus adducted. The condition is characterized by resorption of the distal end of the clavicle. Appears to be more common in males. Pathophysiology uncertain. May relate to avascular necrosis, micro fractures, synovitis. Hx- pain at the AC joint; usually a history of trauma at the site (eg: AC sprain, etc.). PE- pain + deformity at the AC joint. Pain with crossed-chest adduction test. Dx- H&P; Xrays may demonstrate diagnostic sclerosis and cystic degeneration at the distal clavicle. Occasionally you will see widening of the AC joint space. Xrays may be normal if early in the disease process. If questions, consider injection of a local anesthetic into the AC joint. This will produce significant reduction in symptoms. Rx- mostly nonsurgical. PRICES, steroid injections and PT. If continued symptoms, consider surgery. Surgical procedure involves resection of the distal 2.5 cm of the clavicle. Shoulder Pain: Evaluation and Management Gaetano P. Monteleone, Jr., M.D. Dept. of Family Medicine West Virginia University School of Medicine monteleoneg@rcbhsc.wvu.edu www.thesportsmedicinecenter.com REFERENCES Altchek, DA (Ed) Operative Techniques in Sports Medicine. Shoulder Instability.Vol 1(4), 1993. Arciero RA, Wheeler JH, Ryan JB, et al. Arthroscopic Bankart repair vs nonoperative treatment for acute, initial anterior shoulder dislocations. Am J Sport Med. 22(5):589-94, 1994. Bahr R, Craig EV. The clinical presentation of shoulder instability including on the field management. Clin in Sport Med. 14(4): 761-76, 1995. Burkhead WZ, Rockwood CA. Treatment of instability of the shoulder with an exercise program. JBJS. 74-A(6): 890-96, 1992. Carter AM, Erickson SM. Proximal biceps tendon rupture. PSM. 27(6):, 1999. Fongemie AE, Buss DD, Rolnick SJ. Management of shoulder impingement syndrome and rotator cuff tears. Am Fam Phys. 57(4):667-74, 1998. Glockner SM. Shoulder pain:a diagnostic dilemma. Am Fam Phys. 51(7):1677-87, 1995. Glousman RE. Instability versus impingement syndrome in the throwing athlete. Orthop Clin of North Am. 24(1):8999, 1993. Gusmer PB, Potter HG. Imaging of shoulder instability. Clin in Sports Med. 14(4):777-95, 1995. Hovelius L, Augustini GB, Orebro FH, et al. Primary anterior dislocations of the shoulder in young patients. JBJS. 78A(11):1677-84, 1996. Matsen FA, Thomas SC, Rockwood CA: Glenohumeral instability. In Rockwood and Matsen (Eds) The Shoulder. W.B. Saunders, Philadelphia, 1990, pp. 526-622. Mellion MB, Walsh WM, Shelton GL. The team physician's handbook. 2nd edition.Mosby, Phila, PA, 1996. Pagnani MJ, Warren RF: The pathophysiology of anterior instability. Sport Med Arthro Rev. 1(3):177-89, 1993. Rodgers JA, Crosby LA. Rotator cuff disorders. Am Fam Phys. 54(1):127-34, 1996. Siegel LB, Cohen NJ, Gall EP. Adhesive capsulitis- a sticky issue. AFP. 59(7):1843-50, 1999. Speer KP, Hannafin JA, Altchek DW, et al. An evaluation of the shoulder relocation test. Am J Sport Med. 22(2): 177-83, 1994.