Organizational Studies Journal of Leadership

advertisement

Journal of Leadership &

Organizational Studies

http://jlo.sagepub.com/

The Evolution of the Concept of the 'Executive' from the 20th Century Manager to the 21st Century Global

Leader

Joyce Thompson Heames and Michael Harvey

Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies 2006 13: 29

DOI: 10.1177/10717919070130020301

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://jlo.sagepub.com/content/13/2/29

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

Midwest Academy of Management

Additional services and information for Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://jlo.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://jlo.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

>> Version of Record - Jan 1, 2006

What is This?

Downloaded from jlo.sagepub.com at COLUMBIA UNIV on February 9, 2012

Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 2006, Vol. 13, No. 2

The Evolution of the Concept of the ‘Executive’

from the 20th Century Manager to the 21st

Century Global Leader

Joyce Thompson Heames - West Virginia University

Michael Harvey - University of Mississippi

The purpose of this paper is to take an in-depth

look at the profiles of executive skills and

competencies drawn across the expanse of

seventy-five years framed in the backdrop of

management philosophy changes. In the early

1900’s, Chester Barnard outlined the

competencies he felt the executive of the future

At the

would need in the 20th Century.

st

beginning of the 21 Century, Morgan McCall

and George Hollenbeck interviewed over 100

expatriates and reported a list of needed

competencies for the global executive of the 21st

Century. This paper chronicles the changes in

the management arena over that 70 plus year

period of time to frame the backdrop of these

two executive skill profiles. The journey is

interesting and the outcome is surprising at

times. Just as organizations are a product of

their past, so to is the executive of today. He/she

is an anthology of all the things that an

executive needed in early 1900’s, with a couple

dynamic dimensions thrown in to maintain their

sustainable competitive advantage in the new

millennium global marketplace. Key Words:

leadership, executive development, global

management, 20th Century management

training/development, 21st Century global

managers, differences between traditional

managers and global leaders

“Systematic development of global

leaders requires an even stronger, more focused

commitment than does a domestic effort. You

have to know what you are doing, why you are

doing it, and what you want to get out of it.

Without the clarity of commitment, the

complexity of the global environment will

swamp the effort.” (McCall & Hollenbeck,

2002, p. 8)

One of the fundamental questions asked

by scholars and business leaders today is, “How

can a company prepare to effectively compete in

the

hypercompetitive,

complex,

global

environment of the 21st Century?” One of the

central precepts in the management literature is

the necessity to have a well developed,

experienced management team at the helm, or in

other words, experienced, well prepared

executives (Porter, Lorsch, & Nohria, 2004).

However, what constitutes an executive with the

“right stuff” is defined in a variety of ways

(McCall & Hollenbeck, 2002).

There is

reasonable agreement that much of what

tomorrow’s executives need to know can be

learned yet, how they gain that knowledge is

another matter and is not a simple ‘cookie

cutter’ formula. Each person has individual

talents and strengths that have to be

amalgamated into finely tuned organizational

and market skills set (Kotter, 2001).

It is necessary to continuously assess the

transformation from a good executive to a great

executive, as well as how to develop leaders that

are able to insure that organizations survive in

today’s multi-faceted multicultural global

marketplace. To gain insight into what it takes

to be ‘great’ involves comparing past strategies

for developing executives with the espoused

formula for success today. In 1938 Chester

Barnard put forth his thoughts on the traits and

skills of the executive in a ‘cooperative system’

in order to be successful (Wren, 1994).

Recently, after completing an empirical

qualitative worldwide study, McCall and

Hollenbeck (2002) described their vision of the

Downloaded from jlo.sagepub.com at COLUMBIA UNIV on February 9, 2012

30 Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies

uintessential ‘global executive’ and the

necessary skills needed to retain a competitive

edge in today’s complex global business world.

The purpose of this paper is twofold.

The first objective is to provide a brief historical

review and draw a parallel of some of the more

prominent changes in the management

environment across the last 70 years. As we

enter the 21st Century, it would seem to be an

appropriate time to examine the evolution of

desirable characteristics of managers compared

to the past. Barnard’s seminal work in the 1930s

provides the backdrop for the historic

representation of what was thought to be the

necessary qualities of ‘successful’ managers.

Secondly, we develop a comparative analysis of

Barnard’s ‘successful manager’ of the early 20th

Century with that of McCall and Hollenbeck’s

(2002) ‘global executive’ of the 21st Century.

Their empirical research can serve as the

foundation of what is thought to be needed for

success in the global marketplace of the 21st

Century and therefore, be used to foreshadow

what qualities are necessary to succeed in the

future. It is important to continue to look at

current phenomena through the lens of the past

(Wren, 1994); thus the use of the comparison of

the two perspectives should be helpful in linking

the 70 years of change and development in the

management conceptualized by Barnard with the

expectations developed by McCall and

Hollenbeck about developing executives to meet

the challenges in managing in the global

marketplace.

Early Conceptualization of

Management & Management

Development

Discussion about what makes a good

manager/executive/leader and how to develop

such archetypes of commandership has been an

ongoing debate for millenniums. As early as

400 BC, Socrates noted that management skills

were transferable from one setting to another; it

was just a matter of understanding the key areas

of needs by a given group (Watson, 1869). In

the year 1513, Machiavelli penned the first ‘how

to’ book for rulers (executives) and listed his

‘must knows’ for the aspiring ruler (Swain,

2002). Even though the content was technical

Heames & Harvey

and procedural in nature, in 1836 James

Montgomery wrote what is considered by some

as the first text book on management (Wren,

1994). In 1908, Henri Fayol responded to a call

for a theory of management by developing his

now universal ‘principles of management’ that

allowed for what was thought to be an art

(management) to be studied as a discipline in the

classroom (Rodriques, 2001).

A glance back through the pages of

management history illustrates that many

management gurus of the early 20th Century had

their beliefs about what constituted the qualities

of a top notch manager. Each writer supported

the viewpoint that management as a philosophy

and practice, which helped to provide a

backdrop of executive education throughout the

decades. Perhaps ahead of her time, Mary

Parker Follet believed in the communities of

creative practice and suggested that employees

be considered an intrinsic part of the

organization that allowed it to be more

productive (Wren, 1994). Nobel prizewinner

Herbert Simon held strong beliefs about the

decision-making process of executives and firms

in general as he espoused his ideas about

“bounded rationality” (1945). Simon believed

that no one person, including the executive,

could make the complicated decisions of

running an organization in isolation. He defined

the organization as “the pattern of

communications and relations among a group of

human beings, including the processes for

making and implement decisions”, (Simon,

1945, p. 19). And, not to be forgotten; Ralph C.

Davis (1951) wrote “Management is defined as

the function of executive leadership” (p. 12).

Fayol, Follet, Simon, Davis, and many

others made important contributions to our

understanding of management skills and

competencies. But, it is the belief of many that

one name prominently emerges from the early

part of the 20th Century as having a significant

impact on shaping the business landscape of his

era and defining the roles that executives play in

creating viable thriving organizations. Chester

Barnard (1886-1961), as a great scholar, a

notable successful businessman, and a

consultant, through his imagery of the chief

executive of the 1930’s set the foundation for

many to view the development of a world class

leader. Barnard attended Harvard Business

Downloaded from jlo.sagepub.com at COLUMBIA UNIV on February 9, 2012

Evolution of the Concept of the Executive

School where he studied economics, but through

out his life he earned seven honorary doctorates

for his contribution to the understanding of

organizations (Wren, 1994).

During his

presidency of New Jersey Bell, he was noted for

his ‘unbounded’ enthusiasm and concern for his

employees. As a consultant, Barnard assisted

such organizations as the Atomic Energy

Commission, the New Jersey Reformatory, and

the United Service Organization, just to mention

a few (Wren, 1994). Barnard was known for his

belief that the executive “carried out his

functions in a cooperative and democratic

manner rather than in a unilateral autocratic

way” (Gehani, 2002).

Having acknowledged the contributions

of a few of the pioneers of management thought,

it is useful to assess the picture as it is presented

today. A review of the recent literature on

developing executives revealed many prominent

names, too many to capture in this brief note.

Individuals who will no doubt go down in the

history books as having left interesting and

monumental footprints in the sands of

management development include: Peter

Drucker, Michael Porter, and Victor Vroom, just

to name a few. Drucker, the author of 30 books,

touted as being a candidate for being one of the

most influential observers in modern business

history was an advocate of giving employees

responsibility and not empowerment (Galagan,

1998). Porter (1980) outlined the ‘Five Factor

Analysis’ that gave a clearer picture of the

forces that impact profitability in an industry.

Vroom promoted participative management and

matching decision processes to the nature of the

problem (Vroom, 2003).

Also, at the start of the 21st Century, a

number of management experts published

articles that specified the skills and

competencies needed by senior executives in the

future (see Aupperle & Dunphy, 2001;

McKinsey, 2004; Porter, Lorsch & Nohria,

2004).

However, McCall and Hollenbeck

completed an extensive, qualitative, multicountry study in 2002 that generated an allinclusive list of the competencies of the global

executive. Their list was chosen for our basis of

the discussion of the 21st Century executive,

because of the comprehensiveness of their

Volume 13, Number 2, 2006 31

methodology, the amount of data collected for

the study, and the attention given to the holistic

global executive.

Managerial and Societal Transitions

across the 20th Century

Perhaps a constructive first step would

be to examine changes in society in general, and

the business world specifically, to better

understand how and why current conceptions of

management might different from those of the

early scholars.

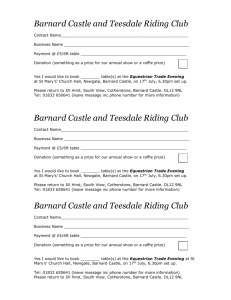

For clarity and to draw

distinctions between various stages in the

development of management thought, we have

divided the 20th Century into five basic eras,

between which paradigm shifts occurred in both

the business arena and more specifically in the

conventional wisdom among management

scholars as to what constituted the practice of

management and what managers needed to be

successful: 1.) Era I, 1900-1945; 2.) Era II, 1945

– 1970; 3.) Era III, 1971 – 1991; 4.) Era IV,

1991 – 2001; 5.) Era V, 2001+. Harvey and

Buckley (2002) synthesized many of the

changes in the economy and management

philosophy very effectively over the 70 plus

years. Table 1 outlines the major tenets of their

piece in a way that parallels the 20th and 21st

Centuries.

Our objective is to tie their

observations of changes to these specific eras as

they emerged as an impetus of change in the

management arena.

Era I: 1900-1945

In the early part of the last century,

the United States experienced a major

transition from a basic agrarian economy to

an industrialized society.

Technology

focused on the mechanization and the

production of goods, the business and

economic sectors became contributors to

critical societal issues (i.e., employee rights,

child labor, health/safety in the workplace,

taxation of corporate entities and the role of

corporation in a society), and improvements

in communications and transportation

broadened external perspectives from local

Downloaded from jlo.sagepub.com at COLUMBIA UNIV on February 9, 2012

32 Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies

Heames & Harvey

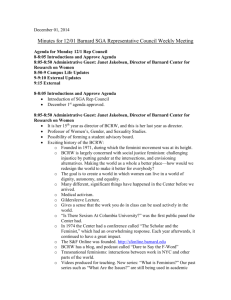

Table 1

Management Environment Transitions from the 20th Century to the 21st Century

20th Century

1. High percentage of manufacturing industries

2. Emphasis on functional expertise

3. Domestic market

4. Legitimate authority in hierarchical

organizational structure

5. Clearly defined operating procedures

6. Well-defined industry boundaries

7. Fairly constant market

8. Bricks & mortar

9. Communication slow & unreliable

10. Technology growth emerging

11. Many employees with similar

responsibilities & skills

(Harvey & Buckley, 2002)

to national and indeed, international

concerns. Making things with machines

became known by a large segment of the

society, as consumers demanded goods in a

quicker time frame. How to make money by

borrowing to maintain and grow businesses was

discovered, creating capital markets. America

discovered that unregulated markets could lead

to monopolies and unfair business practices, and

also fought two World Wars.

Business

organizations grew in wealth and size,

management and ownership separated, and

working for a wage became the norm in the

United States.

Unrestrained competition led to

monopolies, unfair business, poor labor

practices, and massive debt accumulated by

organizations. As a result, society demanded

reforms and the resulting legislation increased

the constraints on business practices. And the

theories of economics taught managers

important lessons in the Great Depression of the

1930s. New Deal programs formed by the

government began to restore the faith in the

power of government to help individuals as

Social Security and many other work programs

were established (Rue & Byars, 2003).

Management’s view of its world was broadened

somewhat to include societal issues external to

the business organization.

This era of

dominance by the organization also spawned the

21st Century

1. High percentage of service industries

2. Emphasis on management processes

3. Foreign markets & cultures

4. Virtual team & network organizational

structures

5. Fluid & reactive operating procedures

6. Ill defined industry boundaries

7. Turbulent market

8. Virtual offices

9. Communication instantaneous & continuous

10. Technology growth exponential

11. Many employees with unique responsibilities

& skills

growth and importance of the trade unions in the

United States. This trend of organizing by labor

provided the appropriate countervailing power

to the economic strength of the corporate world.

This position was strengthen even more during

the depression of the 1930s where the rights of

laborers was abused in many cases due to the

magnitude of need of those out of work/looking

for work during the depression.

From a management perspective the

growing size and complexity of organizations,

and the need to create a skilled labor force, led

to Fayol’s theories of structure and division of

labor (Wren, 1994). While many theorists were

impressed with industrial technology and

mechanization, management discovered that

human assets (largely focused on individuals)

were also important. Management theories and

development began to focus on improving the

productivity of those human assets.

The

acknowledged founder of a body of knowledge

known as scientific management, Frederick

Taylor, stated that training needed to be a part of

the corporation’s responsibility to its employees,

yet he felt the best teacher for managers was

experience (Taylor, 1911).

Taylor also

postulated that the principal objective of

management was to secure the maximum

prosperity for the employer and the employee

(Taylor, 1911).

The 1920’s brought the end of World

War I and the onslaught of more studies of the

Downloaded from jlo.sagepub.com at COLUMBIA UNIV on February 9, 2012

Evolution of the Concept of the Executive

employee and his/her reaction to task and work

environments called the human relations

movement. Chief among these studies were

those conducted at the Hawthorne facility of

Western Electric in Chicago between 1924 and

1933 by a group headed by Elton Mayo (Rue &

Byars, 2003).

The results highlighted the

importance of understanding the social

interaction of workers and the existence of

informal

organizational

social

systems

(Dulebohn, Ferris, & Stodd, 1995). Kaufman

(1993, p. 24) characterized the human relations

focus as “the incorporation of the human factor

into scientific management.” Lewin (1935)

introduced a theory that human behavior is a

function of both person and environment. This

led to the thought that the work environment

needed to give the individual a sense of

belonging for him to function at maximum

capacity and popularized the term group

dynamics.

Era II: 1946-1970

In the three decades following World

War II, large American corporations benefited

from the weakened economies of other nations

such as Germany and Japan. The United States

economy was strong, stable, and experienced

unparalleled prosperity. Producers benefited not

only from the demand from American

consumers, but also from the demand created

when the United States government committed

to rebuild war-torn Europe, as well as the

Philippines and Japan (Tuma, 1971). United

States corporations grew into mega-corporations

that started exploring international holdings to

meet both worldwide demand and to locate

closer to new markets created. Two wars (e.g.,

Korea and Vietnam) and the continuing coldwar arms race continued to fuel the economy

whenever recessions threatened (Library of

Congress, 2004).

The tremendous economic growth and

prosperity of these three decades, while

beneficial to the industrial sector of the

economy, led to a shift away from reliance on

this sector to an emphasis on the development

and delivery of services (Goldstein, 1991). Two

factors explain this shift. First, as Americans

enjoyed high earnings and prosperity, they

began to add services to the ‘goods’ demanded

on a daily basis. Second, technology born in the

Volume 13, Number 2, 2006 33

war efforts and space race began to pervade the

economy. The computer was born during WW

II and greatly perfected during the space race of

the late 1950’s and throughout the 1960’s.

While the computer was a product, its

effectiveness was determined by the software

developed to make it useful as a data processor,

as a reporting system, and in an increasing

number of situations as a data repository (Wren,

1994).

While the industrial world was in full

development mode, the philosophers and

psychologists were in the ‘academic wings’

analyzing the changes from the worker’s

perspective. Team or group dynamics became

the focus of management interest. Deutsch

(1949) suggested that cooperation and

competitive spirit are ever present and

demonstrated that developing cooperative

groups increased production.

Trist and

Bamforth (1951) indicated that it was important

to allow the social dynamics of the group to

exist and that the technical aspects of the job

need not denominate the success of the

workflow. Management continued to place

increasing emphasis on its human assets/capital,

now visualized in group or team dimensions,

rather than as individuals. The advent of the

civil rights movement also highlighted the

disparity among social/ethnic groups as to

opportunities in the workforce. The movement

continues to this day having a direct as well as

an indirect impact on the diversity and vitality of

businesses.

While the computer clearly had a role in

business organizations, it also made significant

contributions to the development of management

theories and practice.

Computers made it

possible to process larger amounts of data and

coupled with a growing body of statistical

techniques, management researchers turned to

empirical studies with greater frequency.

Moreover, as a data repository, computers made

it possible to collect and store large volumes of

data on economic transactions, which

complemented research needs and theory

development (Hammer & Champy, 1993).

Era III: 1971-1991

The years from the early 1970’s through

1991 were a period of economic adjustment for

the United States and much of Western Europe.

Downloaded from jlo.sagepub.com at COLUMBIA UNIV on February 9, 2012

34 Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies

The oil and gas crisis of the 1970’s played a

major role as the increased cost of energy made

the United States and many European companies

less competitive in the manufacturing arena

worldwide. Companies in the United States

faced an increasingly competitive and rough

economic environment laced with technology

advancements, government interventions, and

many

international

dynamics

(Ferris,

Schelenberg, & Zammuto, 1984). Struggles to

survive became the mantra of many boards-ofdirectors. Casio (1993) reported that in the

1980’s United States based manufacturing firms

cut more than two million workers with a

seventeen percent of the dismissals being from

middle management.

However, the demand for services grew

exponentially, and as technology spread

globally, an increasing number of enterprises

from countries other than the United States

became “best in the world” in various industries.

And, because the United States’ consumer

market was the world’s largest, many of these

foreign enterprises entered the United States

market and experienced phenomenal success.

Domestic consumers, ever egalitarian in their

purchasing choices and experiencing some belttightening of their own, bought foreign goods

and services because they were less expensive

and in many cases of higher quality (e.g.,

automobiles, electronic equipment, watches,

cameras, and the like).

Companies in the United States faced an

increasingly competitive and difficult economic

environment laced with dramatically changing

industry

boundaries,

increasingly

rapid

technology

advancements,

government

interventions, and many international dynamics

(Ferris, Schelenberg, & Zammuto, 1984).

Companies in all sectors faced tough strategic

decisions such as downsizing, restructuring, and

rightsizing (Casio, 1993) as well as adopting

new employment philosophies. During this

time, diversity increased due to the increase in

women and minorities in the main stream of

management. This increased diversity provide

the foundation for improving the skill set and

management capabilities of the organization but

also created a tension and in some cases a

conflict among those in the organization.

Michael Porter (1980; 1985; 1986) argued that

business organizations needed to focus on their

Heames & Harvey

value-chain, which led many to create interorganizational alliances with suppliers and

buyers to increase competitiveness. TQM and

business process re-engineering tools were used

to drive out costs and improve quality, speed,

and responsiveness. Many companies turned

more to global markets in an effort to expand

markets and gain added competencies.

Working dynamics were also changing.

Teamwork and the subsequent social facilitation

were recognized as important features, but

negative behaviors were also being identified.

Social facilitation highlighted the point that the

presence of others could sometimes motivate

individuals and spur them to greater efforts.

However, the opposite pattern was also found in

that sometimes individuals worked less hard in

the presence of others than they did alone. This

effect became known as social loafing. Two

primary reasons were given for social loafing 1)

feeling of anonymity (Harkins & Szymanski,

1988) and 2) perception of easy or not

challenging task (Jackson & Williams, 1985).

The 1980’s presented a change in

philosophy and organizations found that it was

important to foster a sense of mutuality and trust

in the relations between management and

workers, to develop employees as assets with the

view of increasing competitiveness, and to assist

the organizations’ compliance with the increased

government regulations (Kochan, Katz, &

McKersie, 1986; Walton, 1985; Beer & Spector,

1984).

The influence of the Japanese

management style was being felt through out the

American corporate landscape. The successful

application of the Theory Z concept contributed

to the recognition that employees represented a

vital resource just as important as capital and

should be managed to facilitate competitive

advantages (Dulebohn, et al., 1995; Carnevale,

Gainer, & Meltzer, 1990).

Era IV: 1992 – 2002

The economy of the 1990’s could best

be summed-up by a statement made by Larry

Chimerine, former Managing Director and Chief

Economist at the Economic Strategy Institute in

an address to the Fibre Box Association's (FBA)

63rd Annual Membership Meeting on April 27,

2003 in Phoenix, AZ. "The 1990s was the

longest period of uninterrupted growth in United

States history, with no inflation, low

Downloaded from jlo.sagepub.com at COLUMBIA UNIV on February 9, 2012

Evolution of the Concept of the Executive

unemployment, and record corporate profits.

Inflation has been taken-off the counter for a

very long time. We're in a permanent disinflationary economy now."

The need to increase speed and

responsiveness led to increasing use of virtual

teams, new forms of organization, virtual

offices, and more adaptive policies and

procedures. As gaining a competitive edge

became increasingly important throughout the

1990’s management researchers began to rethink

old theories and reframe them in a modern

context (Wren, 1994). Pfeffer (1994) argued

that gaining the skill to effectively manage

people was one of the most competitive tools.

Corporate strategy theorists (Birkinshaw, 2001;

Mintzberg, 1991; Prahalad & Hamel, 1990;

Whitney, 2004) argued that the core

competencies of organizations rest in the human

assets and knowledge base of the organization.

Throughout

this

period,

management

organizations and specifically the human

resource management function within them

changed their philosophy and turned to a more

incorporative mindset (Dulebohn, et al; 1995;

Harvey, Buckley, & Novicevic, 2000).

Pfeffer (1994) argued that gaining the

skill to effectively manage people was one of the

most competitive tools. But, with a diverse

workforce that faced more complex problems

and group dynamics than ever before it was not

an easy task. Diverse workforces brought

opportunity and advantage along with

considerable challenges (Ferris, Frink, Bhawuk,

Zhou, & Gilmore, 1996).

The need for

organizations to more proactively use

cooperative and self managed teams to improve

their competitive position was recognized by

many managers. Those teams were being drawn

from across functions, from various business

units, and even from external market sources.

Rodrigues (2001, p. 82) posited that, “United

States based organizations rely more heavily on

the multi-boss, ad hoc organization than in the

past.” Teams – the size of teams, the kinds of

teams, the dynamics of teams, the member

diversity of teams, and the processes of teams –

became the central focus of training initiatives

for employees and managers. Marks, Matthieu,

and Zaccaro (2001) created the team process

taxonomy to try and assist in the research on

teams.

Volume 13, Number 2, 2006 35

One of the primary methods of growth

utilized by organizations is that of employing an

acquisition strategy. This mode of gaining

market power, diversifying risks, and gaining a

broader consumer base has been an inordinately

popular corporate strategy over the last several

decades. In 2005, it was an estimated $2.9

trillion worth of acquisitions made globally. In

what appears to be an unrelenting quest for

limited resources; the need to capture unique

combinations of human resources (i.e.,

management team tacit knowledge) to gain

competitive advantage; the necessary speed of

getting products to a market to remain

competitive; the growing importance of

relational marketing efforts and the resulting

synergistic marketing channel strategies, an ever

increasing number of firms are focusing on

acquisitions to address these marketplace

challenges more than ever before.

Era V: 2002-Date

The dawn of the 21st Century found the

United States facing more economic uncertainty

and increased government regulation.

The

Sarbanes Oxley act, terrorist attacks, and the

subsequent war on terrorism have left executives

of this new day concerned and very cognizant of

the fact they are facing new tumultuous times.

Kiechel and Sacha (1999) listed the following as

trends that will reshape the workplace

throughout the next decade.

• The average company will become

smaller, employing fewer people.

• The

traditional

hierarchical

organization will give way to a

variety of organizational forms, the

network of specialists foremost

among these.

• Technicians, ranging from computer

repairmen to radiation therapists,

will

replace

manufacturing

operatives as the worker elite.

• The vertical division of labor will be

replaced by a horizontal division.

• The paradigm of doing business will

{continue} to shift from making a

product to providing a service.

• Work itself will be redefined:

constant learning, more high-order

thinking, less nine-to-five.

Downloaded from jlo.sagepub.com at COLUMBIA UNIV on February 9, 2012

36 Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies

Heames & Harvey

Buckley (2002) would postulate that it is time to

recognize those changes and make some tough

decisions about what still works for the manager

of today and discard the concepts that no longer

apply. With that thought a look at a comparative

model of the two executives that reside at the

polar ends of the time continuum is in order.

It is obvious that the role of the future

CEO will be riddled with surprises, seven major

issues will dominate according to Porter, Lorsch,

and Nohria (2004). These authors listed the

following as possible pitfalls for future

executives: 1) you can’t run the company solo (it

takes a team of talented people); 2) giving orders

is very costly (using power to unilaterally issue

orders or reject proposals by senior staff will

cost in social capital); 3) hard to know what is

really going on (a magnitude of information and

sources of information); 4) always sending a

message (always being scrutinized both inside

and outside the organization); 5) you are not the

boss (still report to board of directors); 6)

pleasing shareholders is not the goal (activities

and strategies supported by shareholders may

not be in best long term interest of the firm); and

7) recognizing that managers/leaders are still

only human (bound by human joys, fears, hopes,

and personal limits). These seven tenets speak

to the dynamic changes of the multi dimensional

environment in which future executives must

operate.

How do the changes discussed above

affect management development? Burns and

Stalker (1994) would argue that the movement

has been from a ‘mechanistic’ management to an

‘organic’ management.

While Harvey and

A Cross Century Comparative

Assessment of the Concept of the

Executive

20th Century Manager/Executive

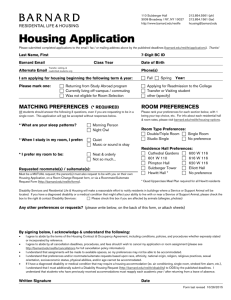

Chester Barnard developed his concept

of what a manager/executive needed to learn to

remain a viable part of the organization and to

guide those for which he was responsible. He

outlined five key competencies (see Table 2)

that every executive of ‘the future’ (as perceived

in the early part of the 20th Century) needed to

brace themselves with beyond their formal

institutional instruction: 1) broad interests and

wide imagination and understanding, 2) superior

intellectual capacities, 3) an understanding of the

field of human relations, 4) an appreciation of

the importance of persuasion in human affairs,

and 5) an understanding of what constitutes

rational behavior toward the unknown and the

unknowable (Barnard, 1948).

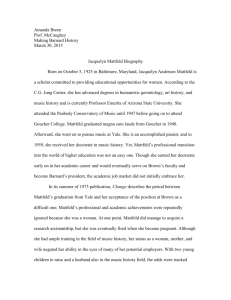

Table 2

A Comparative View of 20th Century Manager with the 21st Century Global Leader

20th Century Manager

(early 1900’s)

1. Broad interests & wide imagination and

understanding

2. Superior intellectual capacities

3. Understanding of the field of human relations

4. Appreciate the importance of persuasion in

human affairs

5. Understand what constitutes rational behavior

toward the unknown & the unknowable

(Barnard, 1948, p. 195-204)

1. Broad interest and wide imagination:

Barnard felt that having a well-rounded liberal

arts education beyond business made

managers/executives more ‘flexible and

adaptable’ in their thinking. While in his role as

1.

21st Century Global Leader

(early 2000’s)

Open minded & flexible

2.

3.

4.

Value-added technical &business skills

Cultural interest & sensitivity

Resilient, resourceful, optimistic, & energetic

5.

Able to deal with complexity

6.

7.

Stable personal life

Possess and engender honesty and integrity

(McCall & Hollenbeck, 2002, p. 35)

company president, he arranged a series of

lectures and readings that were non business

related and lasted up to six non consecutive

weeks for all of the top management, many of

who had college degrees (Barnard, 1948). His

Downloaded from jlo.sagepub.com at COLUMBIA UNIV on February 9, 2012

Evolution of the Concept of the Executive

position was that education could not be

overemphasized.

2. Superior intellectual capacities:

Having survived the Great Depression, World

War I, and World War II, Barnard saw the future

of businesses to be a ‘closer integration of social

activity’ (Barnard, 1948, p. 195). Moreover, he

felt “without education the supply of leaders of

organization competent for conditions of the

modern world would be wholly inadequate”

(Barnard, 1948, p. 194). He drew on that

advance understanding when he spoke to the

concept of intellectual capacities (Barnard, 1948,

p. 197).

There is no doubt in my mind that

training in the more logical disciplines tends to

foreclose the minds of many to the proper

appreciation of human beings. Nevertheless, for

executives, as well as many others, the world of

the future is one of complex technologies and

intricate techniques that cannot be adequately

comprehended for practical working purposes

except by formal and conscious intellectual

processes….to

deal

appropriately

with

combinations of technological, economic,

financial, social, and legal elements; and to

explain them to others so manifestly call for

ability in making accurate distinctions, in

classification, in logical reasoning an

analysis….This means that the student needs

rigorous training in subjects of intellectual

difficulty, thereby to provide himself with the

tools and mental habits for dealing with

important problems.

3. Human Relations: Barnard was clear

on his position of understanding social systems

and recognizing formal organizations as ‘organic

and evolving social systems’. He used the

analogy of organizations not being like

machines, static and fixed; instead they were

compilations of employees who would be

different from location to location. Interaction

and experiences with a given group of people is

needed to fully understand their physical and

psychological needs. This too requires constant

and consistent communication to get to ‘know

your people’.

4. Persuasion: Barnard’s belief s that

one important managerial function was the

process of explaining their actions and beliefs

about company activities. The art of persuasion

is paramount in getting others to accept and even

Volume 13, Number 2, 2006 37

agree with management perceptions.

He

expressed the need to for adequate written and

oral persuasion skills when dealing in human

affairs.

5. Rational behavior: Perhaps the more

difficult of his concepts to understand or that

might be misinterpreted is the last; ‘an

understanding of what constitutes rational

behavior toward the unknown and the

unknowable’.

After having waxed on so

eloquently about the need for superior intellect,

here he adds the intuitive piece. The business

world is full of unknowns and many situations

are faced with incomplete knowledge of all the

facts and thus require the executive to takes

leaps of faith based on past experiences, signals

from the business environment, or just gut

instinct. Barnard prophesized that it is just as

important to be able to exercise wisdom and

instinct as well as intellect (Novicevic, Hench, &

Wren, 2002).

He definitely was a man of vision and

saw dimensions of the future that many of his

time could not comprehend. All five of his

competencies are still needed today, as will be

demonstrated in a subsequent section of this

paper as parallels are drawn between Barnard’s

list and the more modern interpretation of what

competencies are needed by modern global

leaders. All five items drawn from the pages of

his 1948 book are reemphasized today.

21st Century Global Leader/Executive

As stated earlier it was hard to choose

one set of leader characteristics from the list of

noted scholars. However, the McCall and

Hollenbeck (2002) empirically based qualitative

study conducted interviews with over 100 global

executives stationed throughout the world. The

insight of such seasoned leaders was thought to

add to the richness and insights derived from

their research efforts. Their extensive interviews

lead to the following list of competencies: 1)

open-minded and flexible in thought and tactics;

2) cultural interest and sensitivity; 3) able to deal

with complexity; 4) resilient, resourceful,

optimistic, and energetic; 5) honest and

authentic; 6) possess stable personal life; and 7)

value-added technical or business skills (p. 35)

(See Table 2). Each of these points will be

discussed in more details as comparisons and

linkages are drawn between the two lists in the

Downloaded from jlo.sagepub.com at COLUMBIA UNIV on February 9, 2012

38 Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies

next section. McCall and Hollenbeck would be

the first to say that no one list can depict a

universal set of competencies as there is no

‘universal global job.’ “Global competencies,

like global jobs, must be thought of as a mix,

depending on the job” (McCall & Hollenbeck,

2002, p. 34). The world is just too complex and

multi-dimensional.

However, their list is

comprehensive, thought provoking, and

empirically created.

One

additional

interesting

and

apparently new facet to the development of the

global executive is the importance of personal

responsibility for their career paths. They seem

to agree with Peter Drucker who advocates

learning ‘personal management’ is as important

as learning to manage other people (Galagan,

1998). McCall and Hollenbeck address the

organizational and personal responsibilities in

the development of the 21st Century leader.

“Although global executive

development

is

more

complicated and uncertain than

its domestic counterpart, it is

not impossible. The problem is

not a lack of know how – in

fact, many processes for

managing the difficulties of

cross-border assignments have

been well known for years. The

problem is the complexity and

risk; few organizations have

adopted a model robust enough

to fit the challenge and then

committed the time and

resources

necessary

to

implement it…

Given the

added challenge of developing

global talent, a substantial

burden for development falls on

the person who aspires to a

global career. Individuals with

such aspirations need to seek

out international exposure, not

wait for it to find them.”

(McCall & Hollenbeck, 2002,

p.13)

Parallels

Table 2 provides an insight into how

these two executive profiles compare when

Heames & Harvey

positioned juxtaposed. A close look at the list

reveals a number of parallels between the way

Barnard described the 20th Century Executive

and how today’s leaders of the 21st Century

depict their roles as articulated by McCall and

Hollenbeck. First, broad interest and wide

imagination seems to be another way to say

open minded and flexible. Barnard realized in

1948 that the market place was getting more

competitive and changes would come more

quickly. He spoke of staying flexible and

adaptable to allow for the changes that were

occurring in the marketplace. The global leader

of today is faced with changes at a faster pace

and has more information to deal with than any

manager in history. Technology puts more

information at their finger tips than the average

person can process. Therefore 21st Century

leaders must also remain alert and responsive to

the hypercompetitiveness and fast changes of

today’s global business arena.

Second, Barnard spoke of superior

intellectual capacities, where the leaders of

today reference value-added technical and

business skills. It would appear that getting an

education and additional training as a foundation

to success is still a must. Both sets of authors

speak extensively about honing intellectual

abilities by continuously pursuing diverse

educational opportunities. While it is clear that

computer and technical skills are more of a

necessity in the 21st Century, that does note

preclude other forms of education. Life long

learning seems to be their motto, which they

allude to being as much an attitudinal issue as it

is as it is a skill.

Third, perhaps the human relations in

Barnard’s day were framed in a more domestic

backdrop and focused on respecting employee

and employer relations. Yet he still realized that

each organization was unique by virtue of the set

of employees that happen to make up the

employee base. He spoke of organic and ever

evolving systems because of the human element.

The same is true today, however the multinational multi-cultural dimensionality of today’s

organization requires global leaders to be

sensitive to respecting people from around the

world from very diverse backgrounds, beliefs,

and morés.

The fourth comparison evolves around

personal attitude, both the manager of the 20th

Downloaded from jlo.sagepub.com at COLUMBIA UNIV on February 9, 2012

Evolution of the Concept of the Executive

Century and the leader of the 21st Century need

to understand the importance of persuasion,

optimism, and resourcefulness in dealing with

others. Good communication skills, both oral

and written, are a necessity as the executive is

always acting as a spoke person for the

organization and must be able to persuade others

to accept and support organizational objectives.

Both sets of authors also stress the need to be

optimistic and caring when dealing with others

in order to have true relationships with

constitutes.

The fifth and last direct parallel between

the authors addresses the need for dealing with

ambiguity. McCall and Hollenbeck speak to the

issue of complexity distorting the facts that

leaders have to deal with on a daily basis.

Barnard talked about how the executive needs to

understand that the facts needed for decision

making is not in ‘black and white,’ clearly

spelled out. He explains there will be times

where intuition is needed to make decisions

because executives have to deal with the

‘unknown and the unknowable.’

It is interesting that two additional

characteristics are explicitly discussed when

describing the leader of the 21st Century and yet

were not given as descriptives for the 20th

Century manager/executive: 1) stable personal

life and 2) honesty and integrity. Perhaps,

Barnard felt these two items were innate or such

essential characteristics that he did not find it

necessary to put them on paper. Whereas the

authors of today may have recognized the

changing demographic trends of blended

families such as ‘dual–earner lifestyles’, and

situations where both marital partners are

sharing the burden and responsibility for family

care. There is an emerging stream of literature

that discusses the stress issues related to workfamily conflict (Eby, Casper, Lockwood,

Bordeaux, & Brinley, 2005). When addressing

the issues of honesty and integrity, McCall and

Hollenbeck (2002) stated that is necessary for

the leader of today to not only possess these

characteristics, moreover to ‘engender’ them in

others.

Furthermore, they found in their

research that consistent authenticity was crucial

for one to stimulate honesty and integrity in

others. There is evidence that Barnard believed

in and promoted an authentic approach to

leadership and that was an important concept

Volume 13, Number 2, 2006 39

when leaders were faced with ethical decisions

(Novicevic, Davis, Dorn, Buckley, & Brown,

2005). However, he did not list it as one of his

competencies. Again, perhaps he felt it was so

basic it was expected. It still leaves one to

wonder if these personal dimensions (stable

personal life, honesty, and integrity) are just

talked about more today or are they seen as

fading standards that need to be recaptured.

Common Themes

Two common themes run through the

two lists. First, both executive images capture

the value of and the human relational skills

needed to succeed. Each seems to echo the Dale

Carnegie philosophy of understanding your

fellow man and mastering the art of influence

and persuasion (Carnegie, 1936). A second

commonality that ties the two together is the

thought that first-hand experience in the lead

role as CEO is still the most helpful step in the

development of an executive. It appears that

nothing can replace being in the trenches.

People learn to be global from doing global

work (McCall & Hollenbeck, 2002). The 21st

Century global leader lives and operates in a

more complex, faster paced, culturally diverse

business arena. Yet he/she should start with the

principles that Barnard’s 20th Century

manager/executive lived by and then add a keen

understanding of the traits and competencies that

ensure success today as expressed by McCall

and Hollenbeck. Moreover, this paper suggests

that it is necessary to use today’s profile as a

basis for growth for tomorrow.

Final Thoughts

The major contribution of this paper is

the parallelism drawn between the changes in

the management environment and the profiles

thought

to

be

necessary

for

the

executives/leaders of the early 20th and 21st

Centuries. The changes that occurred in the

marketplace over the past 70 plus years are

exceptional and represent significant shifts in the

way executives run global hypercompetitive

enterprises. This comparative analysis helps to

draw on the heritage of the past, while moving

forward into the future, with eyes on changes

still occurring at an ever increasing rate in the

market place. The review of the last 70 plus

Downloaded from jlo.sagepub.com at COLUMBIA UNIV on February 9, 2012

40 Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies

years leaves the realization that it is necessary to

proactively and methodically develop global

executives and continue to add to their store of

talents and skills.

References

Aupperle, K.E. & Dunphy, S.M. (2001). Managerial

lessons for a new millennium: Contributions

from Chester Barnard and Frank Capra.

Management Decision, 39, 156-164.

Barnard, C.I. (1948). Education for executives.

Organization and Management: Selected

Papers. In K. Thompson (Ed) The early

sociology of management & organizations

(pp. 194-206) New York: Routledge –

Taylor & Francis Group.

Barnard, C.I. (1950). The Functions of the Executive.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Beer, M. & Spector, B.A. (1984). Human Resource

management: The integration of industrial

relations and organization development. In

K.M. Rowland & G.R. Ferris (Eds.).

Research in Personnel and Human

Resources

Management,

2,

261-98.

Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Birkinshaw, J. (2001). Why is knowledge

management difficult? Business Strategy

Review, 12, 11-18.

Burns, T. & Stalker, G.M. (1994). Mechanistic and

organic systems. The Management of

Innovation. Oxford: Oxford University

Press.

Carnegie, D. (1936). How to Win Friends and

Influence People. New York: Harper &

Brothers.

Carnevale, A., Gainer, L.J., & Meltzer, A.S. (1990).

Workplace basics: The essential skills

employers Want. San Francisco, CA:

Jossey-Bass.

Casio, W.F. (1993). Downsizing: What do we know?

What have we learned? Academy of

Management Executive, 7, 95-104.

Casio, W.F. & Zammuto, R.F. (1987). Societal

trends and staffing policies. Denver, CO:

University of Colorado Press.

Davis, R.C. (1951). The fundamentals of top

management. New York: Harper &

Brothers.

Deutsch, M. (1949). A theory of cooperation and

competition. Human Relations, 2, 129-152.

Heames & Harvey

Dulebohn, J.H., Ferris, G.R., & Stodd, J.T. (1995).

The history and evolution of human

resource management. In G.R. Ferris, S.D.

Rosen, & D.T. Barnum, Handbook of

human resource management, Cambridge

(pp. 18-41), Mass.: Blackwell Publishers.

Eby, L.T., Casper, W.J., Lockwood, A., Bordeaux,

C., & Brinley, A. (2005). Work and family

research in IO/OB: Content analysis and

review of the literature (1980-2002).

Journal of Vocational Behavior, 66, 124197.

Ferris, G.R., Frink, D.D., Bhawuk, D.P.S., Zhou, J.,

& Gilmore, D.C. (1996). Reactions of

diverse groups to politics in the workplace.

Journal of Management, 22, 23-44.

Ferris, G.R., Schellenberg, D.A., & Zammuto, R.F.

(1984). Human resource management

strategies in declining industries. Human

Resource Management, 23, 381-94.

Galagan, P.A. (1998). Peter Drucker. Training &

Development, 52, 22-28.

Gehani, R.R. (2002). Chester Barnard’s “executive”

and the knowledge-based firm. Management

Decision, 40, 980-991.

Goldstein, I.L. (1991). Training in work

organizations. In M.D. Dunnette & L.M.

Hough (Eds.), Handbook of industrial and

organizational psychology, (2nd Ed). Palo

Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Hammer, M., & Champy, J. (1993). Reengineering

the corporation. New York: Harper Collins

Publishers, Inc.

Harkins, D.G. & Szymanski, K. (1988). Social

loafing and self-evaluation with an objective

standard. Journal of Experimental Social

Psychology, 24, 354-365.

Harvey, M.G., & Buckley, M.R. (2002). Assessing

the ‘conventional wisdoms’ of management

for the 21st Century organization.

Organizational Dynamics, 33, 368-378.

Harvey, M.G., Buckley, M.R., & Novicevic, M.M.

(2000). Strategic global human resource

management: A necessity when entering

emerging markets. In: G. Ferris (Ed.),

Research in personnel and human resources

management, (pp. 173-241). New York:

Elsevier Science, Inc.

Jackson, J.M. & Williams, K.D. (1985). Social

loafing on difficult tasks: Working

collectively can improve performance.

Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 49, 937-942.

Kaufman, B.E. (1993). The origins and evolution of

the field of industrial relations in the United

Sates. Ithaca, NY: ILR Press.

Downloaded from jlo.sagepub.com at COLUMBIA UNIV on February 9, 2012

Evolution of the Concept of the Executive

Kiechel, W., & Sacha, B. (1999). How will we work

in the year 2000? Fortune, 127, 21-44.

Kochan, T., Katz, H., & McKersie, B. (1986). The

Transformation of American Industrial

Relations. New York: Basic Books.

Kotter, J. (2001). What leaders really do. Harvard

Business Review, 79, 85-91.

Lewin, K. (1935). A Dynamic theory of personality.

New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company.

Library of Congress, (2004). www.loc.gov

Marks, M.A., Mathieu, J.E., & Zaccaro, S.J. (2001).

A temporally based framework and

taxonomy of team processes. Academy of

Management Review, 26, 356-376.

McCall, M.W., & Hollenbeck, G.P. (2002).

Developing global executives: The lessons

of international experience. MA: Harvard

Business School Press.

McKinsey Special Quarterly Report (2004). What

global executives think.

Mintzberg, H. (1991). Learning 1, Planning 0: Reply

to Igor Ansoff. Strategic Management

Journal, 19, 464 - 466.

Novicevic, M.M., Davis, W., Dorn, F., Buckley,

M.R., & Brown, J.Q. (2005). Barnard on

conflicts of responsibility: Implications for

today’s perspectives on transformational and

authentic leadership. Management Decision,

43, 1396-4109.

Novicevic, M.M., Hench, T.J., & Wren, D.A. (2002).

“Playing by ear”… “in an incessant din of

reasons”: Chester Barnard and the history of

intuition

in

management

thought.

Management Decision, 40, 992-1002.

Pfeffer, J. (1994). Competitive advantage through

people. Boston, MA: Harvard Business

School Press.

Porter, M. (1980). Competitive strategy: Techniques

for analyzing industries and competitors.

New York: The Free Press.

Porter, M. (1985). Competitive advantage: Creating

and sustaining superior performance. New

York: The Free Press.

Porter, M. (1986). Competition in global industries.

Boston, MA: Harvard Business School

Press.

Porter, M.E., Lorsch, J.W., & Nohria, N. (2004).

Seven surprises for new CEOs. Harvard

Business Review, Oct, 62-72.

Prahalad, C.K., & Hamel, G. (1990). The core

competence of the corporation. Harvard

Business Review, May-June 1990, 79-91.

Volume 13, Number 2, 2006 41

Rodriques, C.A. (2001). Fayol’s 14 principles of

management then and now: A framework

for

managing

today’s

organizations

effectively. Management Decision, 39, 880889.

Rue, L.W., & Byars, L.L. (2003). Management:

Skills and application. (10th Ed.), New

York: McGraw-Hill, Irwin.

Simon, H.A. (1945). Administrative behavior: A

study in decision-making processes in

administrative organizations. (4th Ed. 1997). New York: The Free Press.

Swain, J.W. (2002). Machiavelli and modern

management. Management Decision, 40,

281-287.

Taylor, F.W. (1911). The principles of scientific

management. New York: Harper Brothers.

Trist, E.L. & Bamforth, K.W. (1951). Some social

and psychological consequences of the long

wall method of coal-getting. Human

Relations, 4, 3-38.

Tuma, E.H. (1971). European economics history:

Tenth Century to the present. Palo Alto, CA:

Pacific Books.

Vroom, V.H. (2003). Educating managers for

decision

making

and

leadership.

Management Decision, 41, 968-978.

Walton, R.E. (1985). The future of human resource

management: An overview. In R.E. Walton

& P.R. Lawrence (Eds.), HRM trends and

challenges. Boston, MA: Harvard Business

School Press.

Watson, J.S. (1869). Translation: Xenophon, the

anabasis or expedition of Cyrus and the

memorabilia of Socrates. New York: Harper

& Row.

Whitney, K. (2004). Steve Kerr: Managing the

Business of Learning. Chief Learning

Officer, August, 34-37.

Wren, D.A. (1994). The Evolution of management

thought, (4th Ed.) New York: Wiley.

Downloaded from jlo.sagepub.com at COLUMBIA UNIV on February 9, 2012