Board and Top Management: Changes over the Decades

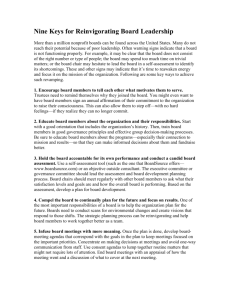

advertisement