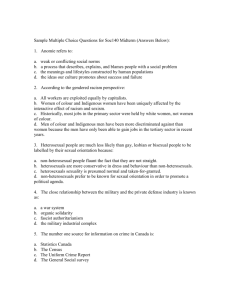

Dimensions of Racism - Office of the High Commissioner on Human

advertisement