Fall vs. Collapse - National Academies of Emergency Dispatch

advertisement

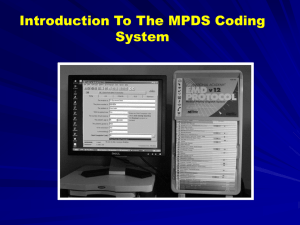

Emergency Medical Dispatch NAEMD Case Study Fall vs. Collapse: A Dilemma in Dispatch Decision-making By Jeff Clawson and Brett Patterson National Academy of EMD For our readers who use the Medical Priority Dispatch System, 9-1-1 Magazine presents this educational Case Study contrasting the use of Protocol Cards 17 and 31 as they pertain to unwitnessed collapses. s we gradually evolve from the art of medical dispatching toward the science of it all, reliable and applicable patient outcomes are being used to f ine-tune the National Academy’s Medical Priority Dispatch System (MPDS). New, previously unavailable data linking scene findings of cardiac arrest with MPDS dispatch codes are providing us with new insight into dispatch decision-making. One of the more vexing dilemmas has been discerning Falls vs. Sudden Unconscious as the Chief Complaint when the patient is reported to have fallen or collapsed, but when the event itself was unwitnessed. A case provided to the Academy by an Accredited Center has shed light on the necessity to ref ine our thinking behind the selection of the correct Chief Complaint regarding these types of calls. The initial transcript of the case begins as follows: Caller: My husband has fallen in the bathroom and he’s not responding to me at all. [location and phone verification performed] EMD: What’s the problem, tell me 90 JASON KIRIAKA A exactly what happened? Caller: I don’t know, I was... I heard a crash. Um, I heard a moan. My husband did not respond. I got up and went into to the bathroom to look. He’s not responding to me all. He is breathing. But we are afraid to move him. EMD: How old is he? Caller: My husband? He’s 63. EMD: Is he conscious? Caller: No. EMD: Is he breathing? Caller: Yes. This call demonstrates an obvious dilemma regarding correct Chief Complaint selection when confronted with unwitnessed information. What part of this information suggests an accidental “fall” and what part suggests a medical “collapse?” The EMD in this case selected Protocol 17 - Falls. Several consultants and EMD instructors did also. However, nearly every lay person that heard the tape picked Protocol 31 Unconscious/Fainting as the Chief Complaint. Why? Because they were not being influenced by a protocol-based notion that is not in sync with the statistical reality of this situation. In this case it would be fair to ask, “What difference does it make?” Both protocols prompt DELTA-level (priority emergency) codes that would more than likely generate the same maximal response conf iguration. If response was the only issue, the selection of either protocol would be clinically sound. However, in addition to response, protocol selection also influences scene and patient safety, information provided to responders, and instructions provided to the caller. The precise categorization of such cases can have a profound effect on the notions of ”trauma“ safety such as moving the patient, beginning and performing air9 - 1 - 1 M a g a z i n e FROM MPDS V11.1 © NAEMD. USED WITH PERMISSION. Protocols 17 [above] and 31 [above, right] of the Medical Priority Dispatch System. New research indicates that Protocol 17 ("Falls") should be used for known falls while unwitnessed ground-level falls in which the patient is not conscious should be processed under Protocol 31 ("Unconscious/Fainting.") way maneuvers, and even at what point the call is terminated by the EMD. We know from available cardiac arrest quotient (CAQ) data that approximately 50% of patients found in arrest at the scene are predicted by 9-D-1 and 9D-2 dispatch codes. Many other Chief Complaint Protocols also predict cardiac arrest, with the DELTA tier capturing nearly 88%. The selection of these protocols is similar to what most clinicians would guess. The primary ones are, in order of frequency: 9 (Cardiac Arrest), 31 (Unconscious/Fainting), 6 (Breathing Problems), 32 (Unknown Problem/Man Down) and, 10 (Chest Pain). Quite unexpectedly, however, 17-D-3 (FallsNot Alert) ranked in the top 5% of determinant codes for CAQ likelihood. No one had predicted this new f inding because Falls are generally regarded, and categorized, as traumatic incidents. Falls are generally perceived to cause an injury, not to be the result of a medical event. In its defense, the MPDS does address correct chief complaint selection with Protocol 17’s first Key Question: “What caused the fall?” However, this probably does not capture a medical “cause” very often and, as a result, medical problems are likely missed more commonly than previously expected. In the case example above, the caller used the word “unresponsive” several times, which is a good description of a truly comatose patient. From a medical point of view, it would be very unlikely that the mechanism of injury from a ground-level fall would be sufficient to cause prolonged unresponsiveness. 92 Although not impossible, such a situation would be quite rare. Another point worth mentioning is the false perceptions of sudden unconsciousness so many of us have acquired from watching years of cowboy, action, and police shows on television. The ease with which TV characters are “knocked out” is simply amazing. Getting “bonked on the head” is not usually sufficient to knock people out much less keep them out. While this might cause an initial collapse, it would likely evolve into either a cardiac arrest situation (not breathing or agonal breathing) or a decreased level of consciousness that would likely, and somewhat quickly, improve to some degree. A very brief seizure-like period might accompany the event but if the collapse was unwitnessed, it probably would not have been seen or discovered by the caller. An unwitnessed, ground-level fall should be considered medical in nature [Protocol 31 - Unconscious/Fainting (Near)] when the patient is discovered to be unconscious or not alert on Case Entry. While the single-blow, low mechanism head trauma commonly seen on TV might certainly cause significant injury and perhaps even momentarily daze the victim, the expectation that such a blow would “knock them out cold” is unrealistic (blows to the head with heavy, solid objects are obvious exceptions). Diagnostically, the actual cause of the case we began with could only result from a few, real-life, clinical scenarios: 1) The patient slipped, hit his head very hard, and was completely unconscious. While certainly possible, it is unlikely that head trauma caused by ground-level fall would be sufficient to cause prolonged unresponsiveness. 2) The patient suffered a sudden, non-perfusing cardiac ar rhythmia. 3) The patient had a seizure. This would also cause initial collapse and unresponsiveness. The patient would likely be breathing regularly, (although predictably noisily), and would slowly recover from her/his unconscious, postictal condition. However, it would be statistically more possible than not for the caller to have observed and reported tonic-clonic, convulsive activity that would commonly be present for 45 to 60 seconds. In the case presented, this might account for the reported noise accompanying, and immediately following, this initially unwitnessed event. In addition, a family member or friend caller would likely mention that the patient was an epileptic or had experienced seizures before. 9 - 1 - 1 M a g a z i n e 4) The patient suffered a catastrophic, intracranial event (hemorrhagic CVA, berry aneurysm). This type of stroke often causes a sudden, initial collapse followed by true coma and a breathing state that could remain regular, if uncompromised by the patient’s airway. If the event was massive and sudden enough to cause a direct fall, it would likely result in a deteriorating state of breathing, from regular to irregular, eventually leading to respiratory arrest. The later is the most likely scenario in the case presented at the beginning of this article. While the 63-year-old age of the patient is consistent with all of the above scenarios, a large stroke, caused by sudden, massive intracerebral (in the brain) or intracerebellar (in or near the brain stem) bleeding, is clearly the “rule out” diagnosis of choice in this case. The near immediate unconsciousness reported by the caller does not bode well for the ultimate survival of such patients who usually die within the first several minutes or hours, despite medical intervention. How might protocol selection be influenced if the event was witnessed? It shouldn’t be unless it is very clear that the origin of the patient’s fall was clearly accidental (mechanical) rather than medical. If the origin of the fall was not known, and the immediate state of the patient’s level of consciousness was decreased or absent, a medical cause should be assumed and Protocol 31 [Unconsciousness/Fainting (Near)] should be selected. A long fall involves a high mechanism of injury and should always be categorized using Protocol 17. Our Research & Standards Division believes there is a need to define a new paradigm, which might be stated using the following Rule: “An unwitnessed, ground-level fall should be considered medical in nature [Protocol 31 - Unconscious/Fainting (Near)] when the patient is discovered to be unconscious or not alert on Case Entry. A related “Proposal for Change” will be submitted to the National Academy of Emergency Dispatch’s Medical Council of Standards for their review and evaluation. In the meantime, be aware that sudden unconsciousness caused by a ground-level fall is rare and should warrant a significant amount of “medical N o v e m b e r / D e c e m b e r 2 0 0 3 cause” suspicion when selecting the Chief Complaint. The outcome of the case presented was fatal. The patient was first breathing noisily and, as he remained wedged between the toilet and bathtub, he slowly stopped breathing before he was finally moved and CPR PAIs were given. ■ Jeff Clawson, MD, is considered the father of modern emergency medical dispatch and is the inventor of the priority dispatch protocol systems concept. He is the founder of the non-prof it National Academies of Emergency Dispatch, the largest certifying and standard-setting public safety organization in the world, with 33,000 members in 20 countries. Brett Patterson is an Academics and Standards Associate for the National Academies of Emergency Dispatch. He also serves as the Academy’s Council of Research Chairman and Board of Curriculum Editor. He can be reached at: Brett@emergencydispatch.org. 93