The Web, Digital Prostheses, and Augmented Subjectivity

advertisement

10

The Web, Digital Prostheses, and

Augmented Subjectivity

PJ Rey and Whitney Erin Boesel

UNIVERSllY OF MARYLAND AND UNIVERSllY OF CALIFORNIA, SANTA CRUZ

The turn of the twenty-first century has been called "the Digital

"and not without reason.

In (post-)industrial nations, most young adults between the ages of 18 and 22 cannot remember a time when computers, cell phones, and the Web were not common features of their

cultural landscape. Today we have profoundly intimate relationships not just th rou:zJ1 these newer

digital technologies, but with them as well. Because we use digital technologies both to

communicate and to represent ourselves across tin1e and across space, we express our agency

through those technologies; at times, we may even

our Facebook profiles or our

smartphones as parts of ourselves. The way we interpret these subjective

has social

and political consequences, however, and it is those consequences that we seek to interrogate

in this chapter.

We begin with a quick overview of the sociological understanding of subjectivity and two

of its key elements: embodiment and the social conditions of subjectification. We argue that

contemporary subjects are embodied simultaneously by organic flesh and by digital prostheses,

while, at the same time, contemporary society maintains a conceptual boundary between "the

online" and "the oflline" that artificially separates and devalues digitally mediated experiences.

Because we collectively cling to the online/ offline binary, the online aspects both of ourselves

and of our being in the world are consequently diminished and discounted. The culturally

dominant tendency to see "online" and "oflline" as categories that are separate, opposed, and

even zero-sum is what Nathan Jurgenson (2011, 2012a) terms

dualism, and it leads us to

erroneously identify digital technologies themselves as the primary causal agents behind what

are, in

complex social problems.

In our final section, we use so-called "cyberbullying" as an example of how digital dualist

frames fail to capture the ways that subjects experience being in our present socio-technological milieu. We argue that the impact of "cyberbullying" violence stems not from the

(purported) malignant exceptionality of the online, but from the very unexceptional continuity of the subject's experience across both online and offiine interaction. At best, digital dualist

frames obscure the causal mechanisms behind instances of "cyberbullying"; at worst, digital

dualist frames may work to potentiate those mechanisms and magnify their harms. For these

reasons, we develop the concept of augrnented

as an alternative framework for interpreting our subjective

ofbeing in the world.The augmented subjectivity framework

173

Digitization

is grounded in two

assumptions: (1) that the categories "online" and "offiine" are coproduced, and (2) that contemporary subjects experience both "the online" and "the offline" as

one single, unified reality.

Dimensions of subjectivity: social conditions and embodiment

To begin, we need to be clear both about what we mean

"subjectivity" and about our

understanding of the relationships between subjectivity, the body, and technology. ~p,eaJ<an2:

broadly, subjectivity describes the experience of a conscious

who is self-aware and who

recognizes her 1 ability to act upon objects in the world. The concept has foundations in classical philosophy, but is deeply tied to the mind/body problem in the philosophy of the

Enlightenment i.e., the question of how an immaterial mind or soul could influence a material body. While some Enlightenment philosophers examined the material origins of the

subject, idealist philosophers and Western religions alike tended to view subjectivity as a transcendent feature of our

they believed that the mind or soul is the essence of a person,

and could

even after that person's body died. This quasi-mystical separation of the

subject from her own body and experience was typified by Rene Descartes, who famously

observed, "I think, therefore I am" (1641 [1993]). Near the end of the Enlightenment, however

- and especially following the work of Immanuel Kant - philosophy began to abandon the idea

the way for the

that it had to privilege either of mind or matter over the other. This

modern understanding of subjectivity as a synthesis of both body and mind.

Western understandings of subjectivity continued to evolve over the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and philosophers came to understand subjectivity as historically situated. They

also began to

that different bodies experience the world in radically different ways.

These points are critical to our argument, so we expand on both.

First, we consider subjectivity to be historically situated or, in other words, that the nature

of subjectivity is fundamentally shaped by the subject's particular time and

For example,

the range of objects available to be acted upon - and thus the range of

- available

thousands of years ago most certainly differed from the range of objects availto human

able to human beings in modern consumer society. We trace this understanding of subjectivity

as historically situated back to the work of G.FW

who observes in Phenomenology tf

Spirit that self-awareness - and, therefore, subjectivity - does not emerge in a vacuum; instead,

our subjectivity arises from our interactions with both other conscious

and the objects

in our environment (1804 [1977]). Since both the objects and the other individuals in an environment will vary based on historical circumstance, it follows that the nature of subjectivity

by those objects and individuals will be particular to that historical moment as well. 2

Our notions of the subject's historical specificity are further reinforced by the work of

Michel Foucault, who focuses on the critical role that power plays in the socially controlled

process of "subjection" or "subjectification" that produces subjects (Butler 1997, Davies

Foucault argues that modern institutions arrange bodies in ways that render them "docile" and

use "disciplinary power" to produce and shape subjectivity in ways that best promote those

institutions' own goals (1975 [1995]). He further argues that, because modern prisons and

prison-like institutions act on the body in different ways than did their medieval counterparts,

they are, therefore, different in how they control the ways that populations think and act. To

illustrate: in medieval Europe, monarchs and religious authorities used public torture and

execution of individuals (such as

the Inquisition) as a tool for controlling the behavior

of the

as a whole. In contrast, an example of modern disciplinary power (e11~an11r:Led

by Jaita Talukdar in this

is present-day India, where a liberalizing state with a burgeon174

The Web, digital prostheses, and augmented subjectivity

pharmaceutical and

sector has encouraged its urban elite to adopt "biotechnological sciences as a style of thought," and to discipline their bodies by adopting new styles

of

Talukdar explains that members of India's new middle classes who focus on

consumption and individual self-improvement in pursuit of more efficient bodies are simultaneously embracing neoliberal ideologies - and in so doing, reshaping their subjectivities in ways

that benefit the multinational corporations that are starting new business ventures in India.

Needless to say, the experience of adopting an inward, "scientific" gaze in order to cultivate a

more "efficient" body is very different from the experience of adopting docile, submissive

behavior in order to avoid being accused of witchcraft (and thereafter,

burned at the

stake). Different techniques of social control therefore create different kinds of subjects - and

as do people and objects, the techniques of social control that subject

will vary

according to her historical time and place.

Second, we consider subjectivity to be embodied - or, in other words, that the nature of

subjectivity is fundamentally shaped by the idiosyncrasies of the subject's body. For example,

being a subject with a young, Black, typically-abled, masculine body is not like being a subject

with a young, white, disabled, feminine body, and neither is like being a subject with a midcllebrown, typically-a bled, gender-non-conforming body. This probably seems intuitive. Yet

in the mid-twentieth century, the field of cybernetics transformed popular understandings of

human subjectivity by suggesting that subjectivity is simply a pattern of information - and that,

at least theoretically, subjectivity could therefore be transferred from one

(human/robot/ animal/ computer) body to another without any fundamental transformation

(Hayles 1999). The cybernetic take on subjectivity turns up in popular works of fiction such as

William Gibson's Neuromancer (1984), in which one character is the mind of a deceased hacker

who resides in "cyberspace" after his brain is recorded to a hard drive. More

in the

television show "Dollhouse" (2009-2010), writer and director Joss Whedon imagines a world

in which minds are recorded to hard drives and swapped between bod,ies.

If you had a body that was very different from the one you have now, would you still experience

in the world in the same

As we write this chapter, the United States is

reacting to the acquittal of George Zimmerman in the murder of Trayvon Martin; as article

after article discusses the color and respective size of both Zimmerman's and Martin's bodies,

as well as the color and sex of the six jurors' bodies, and the role that these bodily attributes

played both in Martin's murder and in Zimmerman's acquittal, it seems impossible to believe

that bodies do not play a critical role in shaping subjectivity, even in the Digital Age.

We follow N. Katherine Hayles in arguing that bodies still play a crucial role in subjecti£caof subjectivity-as-information leads to a

tion. She observes that the cybernetic

devaluation cf

and embodiment" (1999: 48, emphasis in

She asks rhetorically

1), "How could anyone think that consciousness in an entirely different medium would

remain unchanged, as if it had no connection with embodiment?" She then counters by stating

that, "for information to exist, it must always be instantiated in a medium," and moreover, that

information will

take on characteristics specific to its medium (1999: 13).

is building on the phenomenological observations of Maurice Merleau-Ponty,

Here,

who argues that knowledge of the world and, ultimately, the experience of one's own subjectivity is mediated through the body. As he explains, "in so far as we are in the world through

our body ... we

the world with our body" (Merleau-Ponty 1945 [2012]:

Information is neither formed nor processed the same way in metal bodies as in flesh-andblood bodies, nor in female bodies as in male bodies, nor in black bodies as in white bodies,

nor in typical bodies as in disabled bodies, and so on. Even if we believe that subjectivity is

reducible to patterns ;f information, information itself is medium-specific; subjectivity is

175

Digitization

therefore embodied, or "sensory-inscribed" (Farman 2011). Because computer sensors or other

devices for perceiving the world are vastly different from the human body, it follows that, if a

computer were to become conscious, it would have a very different kind of subjectivity than

do human beings of any body type.

If we pull all these pieces together, we can start to get an idea of what subjectivity is and

where it comes from. Put loosely, subjectivity is the experience of being in and being able to

that are available for you to

act upon the world. This sense is shaped by the people and

act both with and upon, and by the institutions and agents that act upon you, all of which are

specific to your particular time and place.Your body is how you act both in and on the world,

as well as the medium through which you experience the world and through which everything

in the world acts upon you in return. Because the kind of body you have has such a profound

impact in terms of both how you can act and how you are acted upon, it plays a critical role

in shaping your subjectivity. Accordingly, we conclude that, for our purposes, subjectivity has

two key aspects: historical conditions and embodiment.

If we are to understand contemporary subjectivity (or any particular subjectivity, for that

matter), we must therefore examine both the contemporary subject's embodiment and her

with her embodiment.

present-day historical conditions. We

Embodiment: "split" subjectivity and digital prostheses

Your embodiment comprises "you," but what exactly are its boundaries? Where do "things

which are part of you" stop, and "things which are not part of you" begin? As a thought experhad a prosthetic

iment, consider the following: Your hand is a part of"you," but what

hand? Are your tattoos, piercings, braces, implants, or other modifications part of"you"? What

about your Twitter feed, or your Facebook profile? If the words that come from your mouth

in face-to-face conversation (or from your hands, if you speak

language) are "yours," are

the words you put on your Facebook profile equally yours? Does holding a smartphone in your

hand change the nature of what you understand to be possible, or the nature of "you" yourself? When something happens on your Facebook profile, does it happen to you? If someone

sends you a nasty reply on Twitter, or hacks your account, do you feel attacked?

Back when Descartes was thinking and (supposedly) therefore being, what did and did not

constitute embodiment seemed pretty clear. The body was a "mortal coil" that thing made of

organic flesh that each of us has, that bleeds when cut and that decomposes after we die; it was

merely a vessel for the "mind" or "soul," depending on one's ideological proclivities. Philosophy's

move away from

priority to either the mind or the body, however, necessarily complicated conceptions of embodiment. Over time, our bodies became not just mortal coils, but parts

of" ourselves" as well. This conceptualization manifested, for example, in certain feminist

well

as hegemonic

discourses that claim men's and women's desires are irreconcilably

different based on how sexual differences between male and female bodies construct experience.

Such perspectives might hold, for example, that women are biologically prone to be ca1:eg1ve~rs.

while m.en are biologically prone to be

and violent.While these naturalistic discourses

recognize the significance of the body in shaping subjectivity, they make a grave error in portraying the body as ahistorical (and thereby fall into biological determinism).

Judith Butler contests the idea that the body, and especially the sexual body, is ahistorical

(1988). Citing Merleau-Ponty, she argues that the body is "a historical idea" rather than a "natural

species." Butler explains that the material body is not an inert thing that simply shapes our

consciousness, but rather something that is peiformed. This is because the materiality of the body

is both shaped and expressed through the activity of the conscious subject. As Butler explains:

176

The Web, digital prostheses, and augmented subjectivity

The body is not a self-identical or merely factic materiality; it is a materiality that bears

""·"'-''Ll"i"-' if nothing

and the manner of this bearing is fundamentally dramatic. By

dramatic I mean only that the body is not merely matter but a continual and incessant

m.ateriau:zmo of possibilities. One is not simply a body, but in some very key sense, one does

one's body and, indeed, one does one's body differently from one's contemporaries and

one's embodied predecessors and successors as well.

1988:521

It is the fluidity of embodiment, as Butler describes it

that we are most interested in. Our

perceptions of an essential or natural body (for example, the idea of a "real" man or woman)

are social constructs, and as such represent the reification of certain performances of embodiment that serve to reinforce dominant social structures.This is why trans* 4 bodies

example)

are seen as so threatening, and a likely reason why trans* people are subject to such intense

violence: because trans* bodies disrupt, rather than reinforce,

ideals of masculinity

and femininity.

Following Butler, we understand subjectivity to have a dynamic relationship to embodiment: both the composition of bodies (embodiment) and the way we perform those bodies

(part of subjectivity) are subject to

both over an individual subject's life course and

throughout history. Given the fluid relationship between subjectivity and embodiment, it is

especially important to avoid succumbing to the fallacy of naturalism (which would lead us to

privilege the so-called "natural body" when we think about embodiment).

Recall from the first section, above, that our embodiment is both that through which we

experience being in the world and that through which we act upon the world. Next, consider

that our agency (our ability to act) is increasingly decoupled from the confines of our organic

bodies because, through prosthetics - which may be extended to include certain "ready-athand" tools (Heidegger 1927 [2008]) and also computers, we are able to extend our agency

beyond our "natural bodies" both spatially and temporally. Allucqufae Rosanne Stone argues

that our subjectivity is therefore "disembodied" from our flesh, and that the attendant extension of human subjectivity through multiple media results in a "split subject" (1994). The

subject is split in the sense that her subjectivity is no longer confined to a single medium (her

organic body), but rather exists across and through the interactions of multiple media.

Stone interrogates our privileging of the "natural body" as a site of agency, and elaborates

on the term "split subject," through accounts of what she terms disembodied agency (1994). In

one such account, a crowd of people

to see Nobel laureate physicist Stephen Hawking

(who has motor neurone disease) deliver a live presentation by playing a recording from his

talking device. Although Hawking does not produce the speech sounds with his mouth, the

crowd considers Hawking to be speaking; similarly, they consider the words he speaks to be his

own, not the computer's. Implicitly, the crowd understands that Hawking is extending his

agency through the device. Of course, Hawking's disembodied agency tl1rough the talking

device is also, simultaneously, an embodied agency; Hawking has not been "uploaded" into

"cyberspace," and his

body is very much present in the wheelchair on the stage.

Hawking's agency and subjecthood,

reside both in his body and in his machine, while

both the "real" Hawking and the "live" experience of Hawking exist in the interactions

performed between human and machine. This is why Stone uses the term "split subjects" to

describe cases where agency is performed through multiple media: because the subject's agency

is split across multiple media, so too is her subjectivity.

Stone refers to Hawking's computerized talking device as a prosthesis "an extension of[his]

the world

will, of [his] instrumentality" (1994: 17 4) .Just as Hawking acts upon and

177

Digitization

through both his organic body and his prostheses (his various devices), the contemporary

subject acts upon and experiences the world through her organic body, through her prostheses, and through what we will call her digital prostheses. Persistent communication via digital

technologies is no longer confined to exceptional circumstances such as Hawking's; in fact, it

has become the default in many (post-)industrial nations. SMS (text messaging) technologies,

smartphones, social media platforms (such as Facebook or Twitter), and now even wearable

computing devices (such as Google Glass) extend our agency across both time and space.

Digital technologies are pervasive in (post-)industrial societies, and our interactions with and

through such technologies are constantly shaping our choices of which actions to take. In addition to conventional prostheses (for example, a walker or an artificial limb), the contemporary

subject uses both tangible digital prostheses (such as desktop computers, laptop computers,

tablets, smartphones) and intangible digital prostheses (such as social media platforms, blogs,

email, text messaging, even the Web most generally) to interact with the people and institutions

in her environment. Similarly, she experiences her own beingness through her organic body,

her conventional prostheses, and her digital prostheses alike.

Again, to us - and perhaps to you, too - these ideas seem obvious. Yet as we elaborate further

in the following section, there is still a good deal of resistance to the idea that interactions

through digital media count as part of "real life." Why is this? In part, Stone suggests that

"virtual [read: digital] systems are [perceived as] dangerous because the agency/body coupling

so diligently fostered by every facet of our society is in danger of becoming irrelevant" (1994:

188). The contemporary subject moves beyond Enlightenment notions of a discrete subject

because her embodiment is the combination of her organic body, her conventional prostheses,

and her digital prostheses. In other words, your hand is a part of you, your prostheses are parts

of you, and your online presences - which are just some of your many digital prostheses - are

parts of you, too.

The contemporary subject is therefore an embodied subject, one whose materiality resides

not in any one distinct and separate medium (organic body, conventional prostheses, or digital

prostheses), but which is performed both within and across multiple media. In order to fully

understand what the implications of such an embodiment are for the contemporary subject,

however, we must turn to examining the historical conditions that shape her. We pay particular attention to how digital technology, especially the Web, is conceptualized in our present

social milieu.

Historical conditions: co-production of "online" and "offline"

In (post-)industrial societies, many of us live in a conceptually divided world - a world split

between "the online" and "the offline." We argue, however, that the categories "online" and

"offline" are co-produced, and so are created simultaneously as the result of one particular attempt

to order and understand the world (aka, the drawing of the boundary between them) Gasanoff

2004, Latour 1993). As such, the categories "online" and "offiine" reflect an ongoing process of

collective meaning-making that has accompanied the advent of digital technologies, but they

do not reflect our world in itself. We further argue that all of our experiences - whether they

are "online,'"'ofiline," or a combination of both - are equally real, and that they take place not

within two separate spheres or worlds, but within one augn1ented reality. In order to understand

the significance of digital technologies within our present historical context, we must explore

the social construction of"online" and "offline," as well as augmented reality itself.

It has become commonplace for writers (for example: Carr 2013, Sacasas 2013) to describe

the world that existed before the advent of the Internet as being "offline." In the version of

178

The Web, digital prostheses, and augmented subjectivity

history that such narratives imply, the world came into being in an "offline" state and then

stayed that way until about 1993, when parts of the world began to gain the ability to go

"online" and access the Web. But this line of thinking is fondamentally flawed. No one could

conceptualize being "offline" before there was an "online"; indeed, the very notion of "offlineness" necessarily references an "online-ness." Historical figures such as (say) WE.B. DuBois,

Joan of Arc, or Plato could not have been "offline," because that concept did not exist during

their lifetimes - and similarly, it is anachronistic to describe previous historical epochs as being

"offline," because to do so is to reference and derive meaning from a historical construct that

did not yet exist. In short, there can be no offline without online (nor online without offline);

these two linked concepts are socially constructed in tandem and depend upon each other for

definition.

The issue with configuring previous historical epochs as "offline" is that doing so presents

the socially constructed concept of "offline" as a natural, primordial state of being. Accordingly,

the concept of" online" is necessarily presented as an unnatural and perverted state of being.

This is the fallacy of naturalism, and it poses two significant problems.

The first problem is that, the more we naturalize the conceptual division between online

and offline, the more we encourage normative value judgments based upon it. It would be

naive to assume that socially constructed categories are arbitrary. As Jacques Derrida suggests,

the ultimate purpose of constructing such binary categories is to make value judgments. He

explains that, "In a classical philosophical opposition [such as the online/ offline pair] we are not

dealing with a peaceful coexistence of a vis-a-vis, but rather with a violent hierarchy" (1982:

41). In this case, the value judgments we make about "online" and "ofiline" often lead us to

denigrate or dismiss digitally mediated interaction, such as when we engage in digital dualism

by referring to our "Facebook friends" as something separate from our "real friends," or by

discounting online political activity as "slacktivism" Qurgenson 2011, 2012a). Our experience

of digitally mediated interaction may certainly be different from our exp~rience of interaction

1

mediated in other ways, but this does not mean that online intera ction is somehow separate

from or inferior to what we think of as "offline" interaction. Rather, if we think more highly

of "offline" interaction, it is because the very advent of digital mediation has led us to value

other forms of mediation more highly than we did in the past. For example, in an age of mp3s,

e-readers, text messages, and smartphones, we have developed an at-times obsessive concern

with vinyl records, paper books, in-person conversations, and escapes into wilderness areas

where we are "off the grid." This tendency both to elevate older media as symbols of the

primacy of "the ofiline," and also to obsess over escaping the supposed inferiority of "the

online,'' is what Jurgenson calls "the IRL [in real life] fetish" (2012b).

The second problem that follows from the naturalistic fallacy is the framing of "online" and

"offline" as zero-sum, which obscures how deeply interrelated the things we place into each

category really are. Most Facebook users, for instance, use Facebook to interact with people

they also know in offline contexts (Hampton et al. 2011). Do we believe that we have two

distinct, separate relationships with each person whom we are friends with on Facebook, and

that only one of those relationships is "real"? Or is it more likely that both our "online" and

"offline" interactions with each person are part of the same relationship, and that we have one

friendship per friend? Similarly, when people use Twitter to plan a protest and to communicate

during a political action, are there really two separate protests going on, one on Twitter and one

in Tahrir Square or Zuccotti park? Just as digital information and our physical environment

reciprocally influence each other, and therefore cannot be examined in isolation, so too must

we look simultaneously at both "the online" and "the offline" if we want to make sense of

either.

179

Digitization

If the conceptual division between "online" and "offline" does not reflect the world of our

lived experiences, then how are we to describe that world? In the previous section, we argued

that the contemporary subject is embodied by a fluid assemblage of organic flesh, conventional

prostheses, and digital prostheses. It likely will not come as a surprise, then, that the contemporary subject's world is similarly manifest in both analog and digital formats

in both

"wetware" and software - and that no one format has a monopoly on being her "reality." Just

as the subject exists both within and across the various media that embody her, so too does her

world exist both within and across the various media through which her experiences take place.

Following Jurgenson, we characterize this state of affairs as augmented reality (2011, 2012a).

Why do we use the term "augmented reality" to describe the single reality in which

"online" and "offiine" are co-produced, and in which information mediated by organic bodies

is co-implicated with information mediated by digital technology? After all,

and

designers of digital technologies have developed a range of models for describing the enmeshment and overlap of "reality as we experience directly through our bodies" and "reality that is

mediated or wholly constructed by digital technologies." Some of those conceptual models

include: "mediated reality" (Naimark 1991); "mixed reality" (Milgram and Kishino 1994);

"augmented reality" (Drascic and Milgram 1996, Azuma 1997); "blended reality" (Ressler et al.

2001, Johnson 2002); and later, "dual reality" (Lifton and Paradiso 2009). "Mediated reality;'

however, problematically implies that there is an unmediated reality - whereas all information is

mediated by something, because information cannot exist outside of a medium. "Mixed reality," "blended reality," and "dual reality," on the other hand, all imply two separate realities

which now interact, and we reject the digital dualism inherent in such assumptions; recall, too,

that "online" and "offiine'; are co-produced categories, and as such have always-already been

ine21..'tricably interrelated. "Augmented reality" alone emphasizes a single reality, though one in

which information is mediated both by digital technologies and by the fleshy media of our

brain and sensory organs. Moreover, "augmented reality" is already in common use, and already

invokes a blurring of the distinction between online and offiine.

Thus, rather than invent a new term, we suggest furthering the sociological turn that is

already taking place in common use of the term "augmented reality" (c.f.Jurgenson 2011, Rey

2011,Jurgenson 2012a, 2012c, Boesel 2012b, Boesel and Rey 2013, Banks 2013a, Boesel 2013).

We use the term "augmented reality" to capture not only the ways in which digital information is overlaid onto a person's sensory experience of her physical environment, but also the

ways in which those things we think about as being "online" and "offiine" reciprocally influence and co-constitute one another. Such total enmeshment of the online and ofiline not only

means that we cannot escape one "world" or "reality" by entering the other; it also means that

in our one world, there is simply no way to avoid the influence either of our organic bodies

(for example, by transporting oneself to "cyberspace"; see Rey 2012a) or of digitally mediated

information and interaction (for example, by "disconnecting" or "unplugging"; see Rey 2012b,

Boesel 2012a).

Augmented reality encompasses a unitary world that includes both physical matter (such as

organic bodies and tangible objects) and digital information (particularly - though not

exclusively - information conveyed via the Web), and it is within this world that the contemporary subject acts, interacts, and comes to understand her own being. In today's techno-social

landscape, our experiences are mediated not only by organic bodies, but also by conventional

and digital prostheses each of which is a means through which we act upon the world and

through which other people and social institutions act upon us in return. In this way, the

rise to a new form of subjechistorical conditions we have described as augmented reality

tivity (as we will elaborate upon in the final section).

180

The Web, digital prostheses, and augmented subjectivity

Before we explain why a new conceptual frame for subjective experience in the Digital Age

is necessary, recall that in this section we have explored how our

conceptually divides

world into two separate

even as the

the contemporary

body, convenmaterial embodiment of her subjectivity is

tional prostheses, and digital prostheses). This observation invites us to ask: What does it mean

for us, as contemporary subjects, that the dominant cultural

holds son1e aspects of our

being to be less "real" than others? What happens when we conceptually amputate parts of

ourselves and of our experiences, and what follows when some expressions of our agency are

deJru12:rat:ed or discounted? We argue that

the ways in which augmented

has affected contemporary subjectivity has grave social and political consequences, as

evidenced

the case study in our final section.

"Cyberbullying": a case study in augmented subjectivity

In October 2012, a 15-year-old

from British Columbia, Canada, named Amanda Todd

committed suicide after several years of bullying and harassment. Todd's death gained international attention, both because a video she'd made and posted to YouTube a month earlier went

viral after her death, and because subsequent press coverage frequently centered on so-called

"cyberbullying" - i.e., the fact that Todd had been

through

mediated interaction in addition to other, more "conventional" methods of abuse.

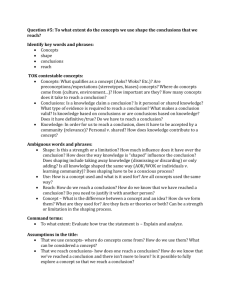

Figure 10.1

A screenshot of Amanda Todd's 2012 You Tube video, "My story: struggling,

bullying, suicide, self-harm"

181

Digitization

Todd never speaks in her video (which she titles, "My story: struggling, bullying, suicide, self

harm"), but nonetheless tells a heartbreaking story across nine minutes of cue cards that she

turns in time to music. During her seventh grade year, Todd and her friends would "go on

webcam" to meet new people and have conversations with them. Through these interactions,

she met a man who flattered and complimented her - and who later coerced her into briefly

showing him her breasts via her webcam ("flashing"). A year later, the man had somehow

tracked her down on Facebook ("don't know how he knew me"), and - after demonstrating

that he now knew her name, her address, the name of her school, and the names of her friends

and family members - he threatened to circulate a screen-captured image ofTodd showing her

breasts through the webcam if she did not "put on a show" for him (a type of blackmail

commonly referred to as "sextortion"). Todd refused to be intimidated, however, and told the

man no. Not long thereafter, the local police came to her family's home to inform them that

"the photo" (as Todd refers to it) had been "sent to everyone."

Trauh1atized, and ostracized by her classmates at school, Todd developed clinical depression,

as well as anxiety and panic disorders; she started using drugs and alcohol in an attempt to selfmedicate. She moved, and changed schools. But a year later, the man returned. This time he

created a Facebook profile, used the image of Todd's breasts as its profile picture, and got the

attention of Todd's new friends and classmates by sending them Facebook "friend requests"

from that profile, claiming to be a new student starting at their school. Todd's classmates at her

second school were as ruthless as those at her first; exiled and verbally abused, she began cutting

herself and changed schools once again. Although she was still isolated and friendless at her

third school, Todd says that things were "getting better" - until she had casual sex with "an old

guy friend" (another teenager) who had recently gotten back in touch with her. In an eerie

echo of the original webcam interaction, Todd's friend seemed to offer the promise of kindness

and affection in exchange for sex ("I thought he liked me," she says repeatedly). Instead, the

boy subsequently arrived outside Todd's school with a crowd of other teenagers, and merely

looked on as his girlfriend physically assaulted Todd. The other teens cheered, encouraged the

boy's girlfriend to punch Todd, and recorded video of the assault with their phones. After her

father picked her up from school, Todd attempted to commit suicide by drinking bleach; when

she came home from the hospital, she found Facebook posts that said, "She deserved it," and "I

hope she's dead."

Todd moved out of her father's house and into her mother's, in order to change schools and

towns once again. Six months later, she says, people were posting pictures of bleach on

Facebook and tagging them as her. As Todd explains across two cards, "I was doing a lot better

too ... They said ... She should try a different bleach. I hope she dies this time and isn't so stupid.

They said I hope she sees this and kills herself." "Why do I get this?" she asks. "I messed up but

why follow me ... I left your guys city... Im constantly crying now... Everyday I think why am

I still here?" Todd goes on to explain that her mental health has worsened; that she feels "stuck";

that she is now getting counseling and taking anti-depressants, but that she also tried to commit

suicide by "overdosing" and spent two days in the hospital. "Nothing stops," she says. "I have

nobody... I need someone," followed by a line drawing of a frowning face. The last card reads,

"My name is Amanda Todd ..." and Todd reaches forward to turn off the webcam. The last few

seconds of the video are an image of a cut forearm bleeding (with a kitchen knife on a carpeted

floor in the background), followed by a quick flash of the word "hope" written across a bandaged wrist, and then finally a forearm tattooed with the words "Stay strong" and a small heart.

Todd hanged herself at home in a closet one month and three days after she posted the video;

her 12-year-old sister found her body.

Todd's suicide sparked a surge of interest in so-called "cyberbullying," and yet the term

182

The Web, digital prostheses, and augmented subjectivity

ov~~rsnnplrt:.ies both what an unknown number of people did to Todd

multiple

did such

in the first place. As

and in multiple contexts) and why those

danah boyd (2007), Nathan Fisk

David A. Banks

and others argue, the term

"cyberbullying" deflects attention away from harassment and abuse ("-bullying"), and redirects

that attention toward digital media ("cyber-"). In so doing, the term "cyberbullying" allows

digital media to be framed as causes of such bullying, rather than simply the newest type of

mediation

which kids

adults) are able to harass and abuse one another. "The

Internet" and "social media" may be convenient scapegoats, but to focus so

on one

set of media through which bullying sometimes takes place is to obscure the underlying causes

of bullying, which are much larger and much more complicated than simply the invention of

new technologies like the Web. Such underlying causes include (to name

a few): teens' lack

of

adult involvement and mentorship (boyd

the contemporary conception of

childhood as

for a competitive adult workforce, and the attendant emphasis on

managing, planning, and scheduling children's lives (Fisk 2012); a culture of hyper-individualism that rewards mean-spirited attacks, and that values "free speech" more highly than "respect"

(boyd 2007); sexism,

and

culture"

2013b). When we characterize

tally mediated harassment and abuse as "cyberbullying," we sidestep confronting (or even

acknowledging) any and all of these issues.

While recent conversations about "cyberbullying" have been beneficial insofar as

have

brought more attention to the fact that some adolescents (almost always

or

nonconforming boys) are

tormented by their peers, these conversations have

how disconnected popular ideas about the Web,

media, and

simultaneously revealed

human agency are from the contemporary conditions that shape human subjectivity. One

concluded, for example, that cyberbullying is "an overrated phenomenon," because most bullies

do not exclusively harass their victims online (Olweus

That study was flawed in its

assumption that online harassment (" cyberbullying") and offiine harassment ("traditional bullyare

exclusive and must occur independently (in other words, that they are

made headlines by

that, "cyberbullying is

zero-sum). Another study (LeBlanc

rarely the

reason teens commit

"and that, "[rn]ost suicide cases also involve realAgain, it is only the flawed concc:~prua1

world bullying as well as depression" (Gowan

division between the "online" and the "real world" (or "offiine") that allows such conclusions

the obvious." Moreover, the term "cyberbullying" has no

to be "findings" rather than

resonance with the people who supposedly experience it: Marwick and boyd (2011) and Fisk

find that teenagers do not make such sharp divisions between online and offiine harassment, and that teens

resist both the term" cyberbullying" and the rigid frameworks that

the term implies.

Conclusion

As we have

and as recent public discourse about "cyberbullying" illustrates, our present-day culture separates digitally mediated experiences into a separate, unequal category, and

often goes so far as to imply that

mediated experiences are somehow "less ~eal." The

contemporary subject is a split subject, one whose embodiment and expressions of agency alike

span multiple media simultaneously and some of those media are digital media. What does it

mean when some parts of our lived experience are treated as disconnected from, and less real

other parts of our lived experience? "Online" and "offiine" may be co-produced conceptual

rather than actual ontological states, but the hierarchy embedded in the

online/ offline binary wields significant social power. As a result, we accord

to some

183

Digitization

aspects of the contemporary subject's embodiment and experience (generally, those most

closely associated with her offiine presence), and we denigrate or discount other aspects of her

embodiment and experience (generally, those most closely associated with her online presence). As such privileging and devaluing is never neutral, this means that contemporary

subjectivity is "split" across media that are neither equally valued nor even given equal ontological priority by contemporary society.

In an attempt to counter the devaluation of those aspects of our subjectivity that are

expressed and embodied through digital media, we offer an alternative framework that we call

augrnented subjectivity - so named because it is subjectivity shaped by the historic conditions of

augmented reality. Augmented subjectivity recalls Stone's notion of split subjectivity, in that it

recognizes human experience and agency to be embodied across multiple media (1994).

However, the augmented subjectivity framework emerges from our recognition of the

online/ offiine binary as a historically specific, co-produced social construction, and so emphasizes the continuity of the subject's experience (as opposed to its "split" -ness), even as the subject

extends her agency and embodiment across multiple media. This is not to suggest, of course,

that digital technologies and organic flesh have identical properties or affordances. Rather, we

seek to recognize - and to emphasize - that neither the experiences mediated by the subject's

organic body nor those mediated by her digital prostheses can ever be isolated from her experience as a whole. All of the subject's experiences, regardless of how they are mediated, are

always-already inextricably enmeshed.

Amanda Todd's story perfectly (and tragically) illustrates how bot~ "online" and "offiine"

experiences are integrated parts of the augmented subject's being, and demonstrates as well

the problems that follow from trying to interpret such integrated experiences through a digital-dualist frame. Todd very clearly experienced her world through her digital prostheses as

well as through her organic body; the pain she experienced from reading, "I hope she's dead,"

was not lessened because she read those words on a social media platform rather than heard

them spoken face-to-face (in that particular instance). Nor was her pain lessened because the

comments were conveyed via pixels on a screen rather than by ink on paper. Neither were

Todd's experiences mediated through her Facebook profile somehow separate from her experiences more directly mediated through the sensory organs of her organic body: another girl

physically assaulting Todd, mediated through smartphones, became digital video; digitally- and

materially-mediated words, remediated by Todd's organic body, became her affective experience of pain, which became cuts in her flesh, and which - mediated again by several digital

devices and platforms - became a still image in a digital video. The digital image of Todd's

breasts that strangers and classmates alike kept circulating was always-already intimately linked

to Todd's organic body.Neither Todd's beingness nor her experience of being can be localized

to one medium alone.

Similarly, both Todd and her tormentors are able to express their agency through multiple

media. Todd's harassers were able to continue harassing her across both spatial and temporal

distance; the man who made the screen-captured image of her breasts, and then repeatedly

distributed that image, understood precisely the power he had to affect not just Todd, but also

the other teenagers who tormented Todd after seeing the photo.

It is important to note that bullying is not the only type of social interaction that we

experience fluidly across online and offline contexts. Support, too, transcends this

constructed boundary, as a significant number of scholars have argued (for example: Turner

2006, Chayko 2008, Gray 2009, Baym 2010,Jurgenson and Rey 2010, Davis 2012, Rainie

and Wellman 2012, Wanenchak 2012). Todd and her seventh grade friends understood that

they could extend themselves through their webcams, and so were able to view webcam sites

184

The Web, digital prostheses, and augmented subjectivity

as ways to connect with other

of her reasons for making the video she posted to

YouTube, Todd writes, "I hope I can show you guys that everyone has a story, and everyones

future will be

one day, you

gotta pull

" Here, Todd clearly understands

that she can act upon future viewers of her video, and she

that she will do so in a

tive, beneficial way.

The characteristic continuity of the augmented subject's online and offline

1s

clearly illustrated

and yet - with respect to teen-on-teen harassment that continuity

becomes markedly less apparent if we fixate on the digitally mediated aspects of such harassment as "cyberbullying." If we look past the reified division between "online" and "offline"

however, it becomes clear

that each of us living within augmented

1s a

human subject, and that each of us has one continuous

of being in the world.

than

Digital prostheses do have different properties and do afford different ranges

do their conventional or organic counterparts, but we should not focus on the properties

type of media to the detriment of our focus on the actions and moral responsibilities of human

agents. Focusing on one particular means through which

enact violence against each

other (for

through digitally mediated

will never solve the problem of

violence; as

argues, bullying will continue to occur through whatever the newest medium

of communication is, because bullying is not nor has it ever been unique to any

available medium (2007).

Rather than hold digital media

or even as

we need to

that

digitally mediated

and interactions are simply part of the day-to-day world in

which we live. Digital media are a distinctive part of our cultural moment, and they are part of

ourselves. When we view contemporary experience through the frame of augmented subjecrecognize the inextricable enmeshment of online and ofiline

tivity

and, in so

it is clear that what happens to our digital prostheses happens to us. For this

reason, we state unequivocally that moral regard must be extended to these digital prostheses.

Similarly, each action we take through our digital prostheses is an

of our agency and,

as such, is something for which we must take responsibility. That said, your authors are not

cyberneticists; we do not believe that subjectivity can or ever will transcend the organic body,

or that deleting someone's digital prosthesis is the same thing as killing that person in the flesh.

Although contemporary subjectivity is augmented

digital technology, organic bodies are still

an essential and inseparable dimension of human "''"''""'r"""r'""'

Information depends critically on the medium in which it is instantiated.

essential that we acknowledge all of the media that comprise the augmented

tal prostheses, her conventional prostheses, and her

flesh. Rather than trade digital

denialism for flesh

we argue that subjectivity is irreducible to a11y one medium.

Instead, we must

that contemporary subjectivity is augmented, and we must grant all

aspects of the subject's

equal countenance.

Acknowledgements

This paper could not have taken the form that it did without ongoing inspiration and support

from a vibrant

community. In particular, the authors would like to ac1c.nc)wtedl2:e

their

blog: David A. Banks, Jenny L. Davis, Robin James, Nathan

Jurgenson, and Sarah Wanenchak. Conversations with

Antley, Tyler Bickford, Jason

Farman, and Tanya Lokot have also provided the authors with valuable insight.

185

Digitization

Notes

2

3

4

We refer to the

subject as "her" (rather than "they" or "him") for purposes of clarity and readability, and have chosen to use the feminine pronoun "her" in order to counter the earlier tradition of

using generalized masculine pronouns.

This observation was foundational to Karl Marx's understanding of ideology and theory of historical

materialism, and to the discipline of sociology more broadly.

It is useful to distinguish the socio-historical nature of subjectivity from the concept of the self (even

if the two are often used interchangeably in practice). Nick Mansfield (2000: 2-3) cautions:"Although

the two are sometimes used interchangeably, the word 'self' does not capture the sense of social and

cultural entanglement that is implicit in the word 'subject': the way our immediate

life is always

caught up in complex political, social and philosophical that is, shared - concerns."

"trans*" is an umbrella term that encompasses a broad range of non-cisgender identities, for c.-.,a11cq..wc,

transgender, trans man, trans woman, agender, genderqueer, etc.

References

Azuma, R. 1997. "A Survey of Augmented Reality." Presence: Teleoperators and Vinual Environments 6(4):

355-385.

March 1, 2013,

Banks, D.A. 2013a. "Always Already Augmented."

cyborgology I 2013I03I01 liilways-a lready-mtgmemed.

Banks, D.A. 2013b. "What the Media is Getting Wrong about Steubenville, Social Media, and Rape

Culture." Cybo1golog}~ March 23, 2013,

media-is-,r;etting-wrong-about-steuberwille-social-media-and-rape-culture.

Baym, N. 2010. Personal Connections in the D(gital Age. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Boesel, WE. 2012a. "A New Privacy (Full Essay)."

August 6, 2012,

Boesel, WE. 2012b. "The Hole in Our Thinking about Augmented Reality." Cyborgology,August 30, 2012,

http: I lthesodetypttf;es.01x lcybo1golo<i[Y 1201210813 O!the-hole-in-our-tlzinkin,g-about-aus;mented-reality.

Boesel, WE. 2013. "Difference Without Dualism: Part III (of 3)."

April 3, 2013,

Boesel, WE. and Rey, PJ 2013. "A Genealogy of Augmented Reality: From Design to Social Theory (Part

One)." Cyborgology, January 28, 2013,

augmented-realityfrom-design-to-social-t/1eory-part-011e.

boyd, d. 2007. "Cyberbullying."

April 7, 2007, www.zephori,i.org/thoughts/arc/1ives/2007 I

04107 lcyberbullying.html.

Butler, J. 1988. "Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist

Theory." Theatre Journal 40( 4): 519-531.

in Su~jection. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

Butler,]. 1997. The Psychic

Carr, N. 2013. "Digital Dualism Denialism." Rou,gh Type, February 27, 2013, w•i1w..ru11v111

Chayko, M. 2008. Portable Cormnunities: The Social Dynamics ~f Online and J\!lobile Connectedness. New York:

State University of New York Press.

Davies, B. 2006. "Subjectification: The Relevance of Butler's Analysis for Education." British Journal ~f

of Education 27 (4): 425-438.

Davis, J.L. 2012. "Prosuming Identity: The Production and Consumption of Transableism on

Transabled.org." American Behallioml Scientist. Special Issue on Prosumption and Web 2.0 edited by

George Ritzer. 56(4): 596-617.

Derrida, J. 1982. Positions, trans. Alan Bass. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

Descartes, R. 1641 [1993]. ;\!/editations on First Philosophy: Jn Which the Existence ~f Cod and the Distinctio11

Soul from the

Demonstrated. Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing Company.

Drascic, D. and Milgram, P. 1996. "Perceptual Issues in Augmented Reality." In Proc. SPIE Stereoscopic

Displays and Virtual Reality Systems /II, 2653: 123-134. San Jose, California.

Theory: Embodied Space a/lii Locatii;e Media. London and New York:

Farman, J. 2011. 1\!Iobile

Routledge.

Fisk, N. 2012. "Why

July 14, 2012,

186

The Web, digital prostheses, and augmented subjectivity

Gibson,W 1984. Neuromancer. New York: Ace Books.

Gowan, M. 2012. "Cyberbullying Rarely Sole Cause Of Teen Suicide, Study Finds."

October 25, 2013, w1,i,•w.lmf{mQCOnµos£.ccw11

Gray, M. 2009. Out in the Country: Youth, Afedia, and Queer

University Press.

Hampton, K., Goulet, L.S., Rainie, L., and Purcell, K. 2011. "Social net:wclrkmg

Internet and American

Pr~ject,June 16, 2011, wu1w.1uei111m.ten1et.

Hi~tfin/f,ton

Post,

Bodies in Lv·1Je1·ne1'1cs. Literature, and lr!fonnatics.

Chicago and London: University

Press.

Hegel, G.F.W 1804 [1977]. P/Jenowenolo«?y <?f ::,pirit, trans. A.V. Miller. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Heidegger, M. 1927 [2008). Bein«? and Time. New York: Harper Perennial/Modern Thought.

Jasanoff, S. 2004. "Ordering

Ordering

In Stares qf

The Co-production t?f

Science and Social Order, edited by S.Jasanoff, 13-45. New York and London: Routledge.

Johnson, B.R. 2002.

and Place: The Relationship between Place,

and

Paper

at ACADIA 2002: Thresholds Between

£1nd Virtual, Pomona, CA.

http: I l_{i1Culty. w11s!dn,r,;ton.ed11/b~j /presentations lacadia0210. d~{i1uft. html.

N. 2011. "Digital Dualism versus Augmented

24, 2011,

Jurgenson, N. 2012a. "When Atoms Meet Bits: Social Media, the Mobile Web and

Revolution." Future Internet 4: 83-91.

Jurgenson, N. 2012b. "The IRL Fetish." The New Inquiry,June 28, 2012.

October 28, 2010,

Latour, B. 1993. vW: Have Never Been lvlodem. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

of 22 Cases." Paper pn~se1rited

LeBlanc,J.C. 2012. "Cyberbullying and Suicide: A Retrospective

at Amerirnn Academy

National

and Exhibition, October 2012, New Orleans, LA.

Abstract:

Lifton, J. and Paradiso,

"Dual reality: Merging the Real and

" In First International

Cor!ference, Fa VE 2009, Berlin,

27-29, 2009, Revised Selected

edited by F LehmannGrube and J.

12-28. Berlin, Germany: JP•"'·'"'-'-•·

Mansfield, N. 2000. Subjectivity: Theories

Se!ffrom

to Hamway. New York: New York University

Press.

Marwick, A. and boyd, d. 2011. "The Drama! Teen Conflict, Gossip, and Bullying in Networked Publics."

Paper presented at A Decade in Internet Time: Symposium on the Dynamics of the Internet and

Society, Oxford, UK, September 2011.

Merleau-Ponty, M. 1945 [2012]. Phenomenology of Perception. London and New York: Routledge.

Milgram, P and Kishino, F. 1994. "A 1axonomy of Mixed

Visual Display." IEICE Thznsactions on

b!formation Systems E77-D: 12.

Naimark, M. 1991. "Elements of .1.,~.<U"P"'-" Imaging: A Proposed Taxonomy." In SPIEISPSE Electronic

vmr1'P1·1n1•:J' 1457. San Jose, CA.

Olweus, D. 2012. European journal of Del!elopmental

9(5): 520-538.

Rainie, L. and Wellman, B. 2012. Networked: The New Social Operating System. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Ressler, S.,Antonishek, B.,Wang, Q., Godil,A., and Stouffer, K. 2001. "When Worlds Collide: Interactions

between the Virtual and the Real." Proceedings on 15th Ti.vente Workshop

lnteractio11s in Virtual vVi.nlds, Enschede, The Netherlands, May 1999.

Rey, PJ 2011.

and the Augmented

Inhabit."

10, 2012,

Sacasas, L.M. 2013. "In Search of the Real." The

2012107104/in-pursuit-ofthe-real.

187

Digitization

Stone, A.R. 1994. "Split Subjects, Not Atoms; or, How I Fell in Love with My Prosthesis." Cor!figurations

2(1): 173-190.

Todd, A. 2012. "My Story: Struggling, Bullying, Suicide, Self Harm" [video]. Retrieved July 2013 from

wu1w.youtube.com/watc/1?v=vOHXCNx-E7E.

Turner, E 2006. From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the Rise <?.f

D(r;ital Utopianism. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

Wanenchak, S. 2012. "Thirteen Ways of Looking at Livejournal." Cyb01gology, November 29, 2012,

http: I I thesodetypa,r;es. oi;g I cyboi;gology I 2012I11I2 9 I thi rteen-ways-<?_f-looking-at-livejournal.

188