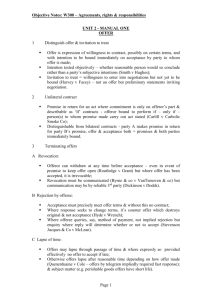

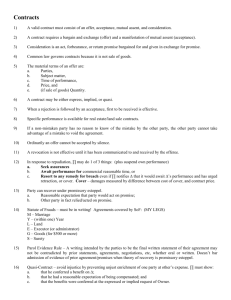

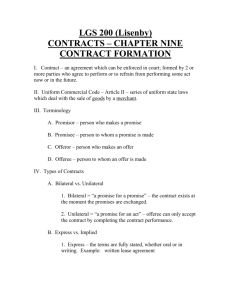

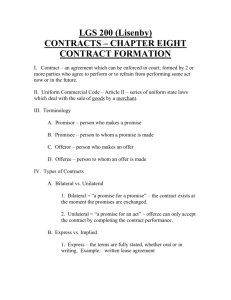

Contracts

advertisement