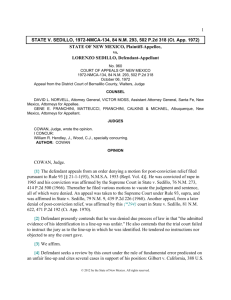

View PDF - Boston College International & Comparative Law Review

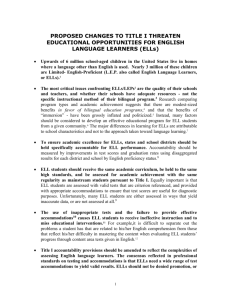

advertisement