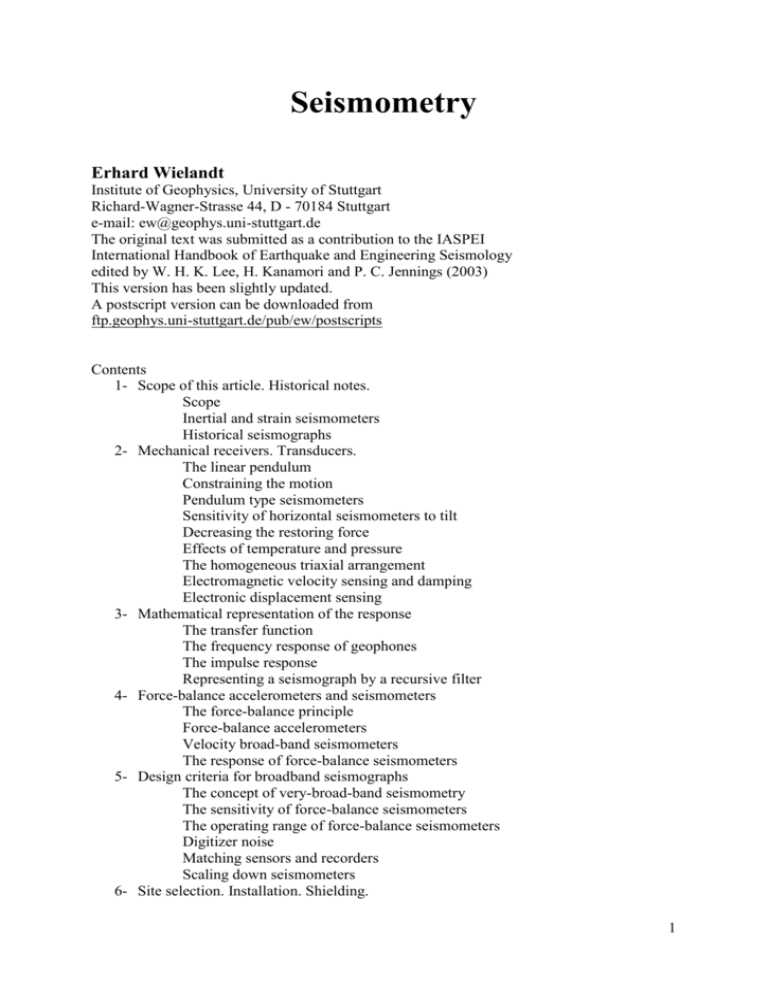

Seismometry

advertisement