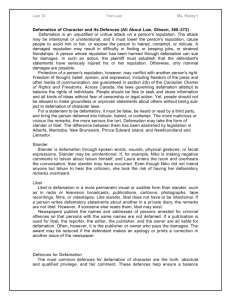

View Article - Singapore Academy of Law

advertisement