UNIVERSALS IN THE CONTENT AND STRUCTURE OF VALUES

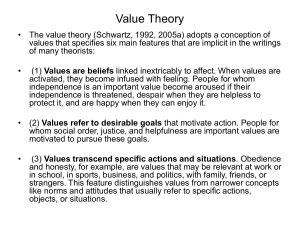

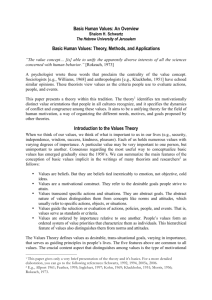

advertisement