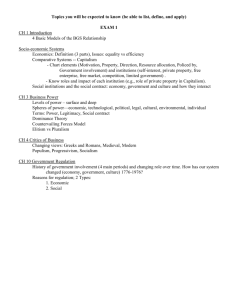

Resource Pack for Social Care

advertisement