THE ANNALS OF HUMANITIES COMPUTING: THE INDEX

advertisement

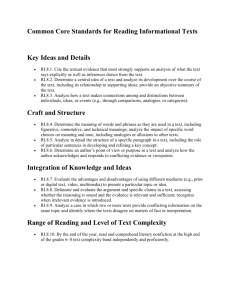

THE ANNALS OF HUMANITIES COMPUTING: THE INDEX THOMISTICUS R. BUSX Introduction I entered the Jesuit order in 1933. I was then 20. Later my superior asked me: "Would you like t o become a professor?" "In no way!" My wish was t o be a missionary to take care of the poor. "Good. You'll do it, all the same." By 1941, when Italy entered the Second World War, I had been assigned t o work towards a Ph.D. in Thomistic philosophy at the Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome. My research was aimed at exploring the concept of presence according t o Thomas Aquinas. At that time the Italian Navy was interested in drafting me as a chaplain, an assignment which would have greatly appealed to me. My superior, however, managed t o have someone else take the post. Thus, up until the end of 1945, my principal interest was focused on philosophy and philosophical texts whlle I was surrounded by bombings, Germans, partisans, poor food and disasters of all sorts. According to the scholarly practices, I first searched through tables and subject indexes for the words of praesens and praesentia. I soon learned that such words in Thomas Aquinas are peripheral: his doctrine of presence is linked with the preposition in. My next step was to write out by hand 10 000 3" X 5" cards, each containing a sentence with the word in or a word connected with in. Grand games of solitaire foilowed. On January 28, 1946, I defended my doctoral thesis, which was published in 1949: La Terrninologia Tomistica dell'lnteriorita: Saggi d i metodo per una interpretazione della rnetaftsica della presenza (Milano: Bocca). While I was involved with this research, two major considerations became evident. I realized first that a Fr. Roberto Busa, S.J., CAAL-Aloisianum, 21013 G d a r a t e , Italy. philological and lexicographical inquiry into the verbal system of an author has t o precede and prepare for a doctrinal interpretation of his works. Each writer expresses his conceptual system in and through his verbal system, with the consequence that the reader who masters this verbal system, using his own conceptual system, has to get an insight into the writer's conceptual system. The reader should not simply attach t o the words he reads the significance they have in his mind, but should try t o find out what significance they had in the writer's mind. Second, I realized that all functional or grammatical words (which in my mind are not 'empty' at all but philosophically rich) manifest the deepest logic of being which generates the basic structures of human discourse. It is .this basic logic that allows the transfer from what the words mean today t o what they meant t o the writer. In the works of every philosopher there are two philosophies: the one which he consciously intends t o express and the one he actually uses t o express it. The structure of each sentence implies in itself some philosophical assumptions and truths. In this light, one can legitimately criticize a philosopher only when these two philosophies are in contradiction. In 1946 as a result of these preliminary conclusions, I started to think of an Index Thornisticus (henceforth IT), i.e., a concordance of all the words of Thomas Aquinas, including conjunctions, prepositions and pronouns, t o serve other scholars for analogous studies. This project has been considered favorably by such scholars as Aldo Ferrabino, Etienne Gilson, Werner Jaeger and the Jesuits Rink Arnou, Charles Boyer, Paul Dezza, Ludwig Naber. It was clear t o me, however, that t o process texts containing more than ten million words, I had t o look for some type of machinery. In 1949, accompanying an Italian student, Giulio Crespi Ferrario from Busto Arsizio, I visited approximately 25 American Universities from 84 R. Busa / The Index coast t o coast, asking about any gadget that might help in prod'ucing the type of concordance I had in mind. Mr. H.J. Krould, Chief of the European Affairs Division of the Library of Congress, provided me with the answer in the person of Jerome Wiesner of M.I.T., who sent me t o IBM in New York City, where someone was assigned t o examine my project. I knew, the day I was to meet Thomas J. Watson. Sr., that he had on his desk a report which said that IBM machines could never do what I wanted. I had seen in the waiting room a small poster imprinted with the words: "The difficult we do right away; the impossible takes a little longer," (IBM always loved slogans). I took it with me into Mr. Watson's office. Sitting in front of him and sensing the tremendous power of his mind, I was inspired t o say: "It is not right t o say 'no' before you have tried." I took out the poster and showed him his own slogan. He agreed that IBM would cooperate with my project until it was completed "provided that you do not change IBM into International Busa Machines." I had already informed him that, because my superiors had given me time, encouragement, their blessings and much holy water, but unfortunately no money, I could recompense IBM in any way except financially. That was providential! In addition Mr. Watson appointed Paul Tasman t o assist me in the project. His broad mind realized immediately the feasibility and values of the project, as did Dorothy Tasman, his wife. His role in this project has been an essential one: without his contribution it could have failed many times. In the next days, Cardinal Spellman informed Mr. Watson, through the gracious efforts of Fr. Robert I. Gannon SJ, the former president of Fordham University, that my project was a valuable one, and that I had the proper academic qualifications. In the three decades it took t o complete the project, a time fdled with changes, the support of my superiors, the management of IBM and the Italian Financing Committees continued even when it was not clear how long the project could take. When I returned to Italy, the IBM office in Milan offered full assistance. I succeeded in producing single word-cards from sentence-cards, progressively scanning the blanks in each column of the sentence-cards. In 195 1 at the XVIII World Conference of Documentation held in Rome, my volume entitled S. 7'homae Thornisticus Aquinatis Hymnorum Ritualium: Varia Specimina Concordantiarum: A First Example of a Word Index Automatically Compiled and Printed by IBM Punched Card Machines (Milano: Bocca 1951) was exhibited. The many Italian IBMers who had collaborated were happy: G. Vuccino, Cl. Folpini, A. Cacciavillani (I regret that I might have skipped over some names, but they know how grateful I am t o them). Although some say that I am the pioneer of the computers in the humanities, such a title needs a good deal of nuancing. A propos of this, Mr. Lee Loevinger in the Minnesota Law Review, 3 3 (5) April 1949), in an article on jurimetrics said: "Machines are now in existence which have so far imitated thought processes that they can solve differential equations. Why should not a machine be constructed to decide lawsuits?" (p. 471). And on the stacks of the IBM library in New York City I had spotted a book (whose title I have forgotten), which was printed some time between 1920 and 1940: in it someone mentioned that it was possible to make lists of names by means of punched cards. Maybe others too may claim that they have worked in this area prior to me. Yet, isn't it true that all new ideas arise out of a milieu when ripe, rather than from any one individual? If I was not the one, then someone else would have dealt with this type of initiative sooner or later. To be the first bne having an idea is just chance. If there is any merit, it is in cultivating the idea. During the following years I experienced the wisdom of another slogan, attributed t o an American, Thomas Edison: Genius is 1% inspiration, 99% perspiration. From punched cards to magnetic tapes Obviously, I started with punched cards equipment, and as a consequence confronted two objectives. The first was t o establish a file of punched cards, with one word on each card including reference and typological codes. On the back of each card a maximum of 12 lines, printed in the spaces between the rows of holes, formed the context of the word that was punched on the card. For this task I was given an IBM 858 Cardatype, which was a kind of a transitional link between unit record and data processing machines. Its input was made up of sentence- R. Busa / The Index Thornisticus ina [ex 9M vas Ilaacver to he a ,ee 5) [ani:nInhe ad :h it :ts rs :a se le se 3r e. a. n is PC- cards that were already punched and verified. It had two outputs: on one side, a card, punched and interpreted, with reference and codes, for each single word occurring in the sentence; on the other, a maximum of 12 sentence-cards on a lithographic master plate. This plate was then used (in an American Davidson machme imported t o Gallarate and operated by a Jesuit brother, Federico Masiero) t o print the context on the back of the corresponding word-cards. I still remember how difficult it was t o calibrate the lines between the punched holes, as the paper plate stretched progressively during operation. I still have a file of 800000 such cards. The second objective was to find out a practical way for listing a concordance using sentence-cards to be sorted and grouped for each key-word. One day I learned from the newspapers that an Episcopalian minister, Rev. John W. Ellison, who was preparing a concordance of the Revised Version of the Bible (he published it in traditional ways in 1957), had used Remington magnetic tapes, which at that time were not plastic but iron. 1 went t o shake hands with him and said: "You are a great ally of mine!" Immediately after I went t o IBM: "See what Remington is doing?" Since that time the processing of the IT has been done malnly by computers and punched card equipment was used only peripherally. A project of many facets In Italy I worked in IBM offices for a few years. In 1954 I started my own punching and verifying department; two years later I established my own processing department, but employing large computers always in IBM premises. That year I started a training school for keypunch operators. For all those admitted, the requirement was that it was their first job. After a month of testing, only one out of five was accepted for a program of four semesters, eight hours per day.. The success was excellent: industries wanted t o hire them before they had finished the program. Their training was in punching and verifying our texts. To make the switch from the Latin t o the Hebrew and Cyrillic texts, only two weeks were needed, and it was not even necessary t o attach these new alphabets t o the keys of the puncher. In punching 85 these non-Roman alphabets, the process was less speedy but with fewer errors. This school continued until 1967, when I completed the punching of all my texts. In that same year I moved my operations t o Pisa, two years later t o Boulder, Colorado, and in 1971 t o Venice, wherever IBM provided computer time. In addition to the 10 600 000 words of the IT, I processed five million more words, Italian, English, German, Russian, ancient Greek and Hebrew, Aramaic and Nabataean, using Cyrillic, German Gothic, Greek and Hebrew alphabets and going from right to left in Hebrew. The subjects ranged from nuclear physics and mathematics abstracts t o Qumran Scrolls and works of Dante,Kant, and Goethe. The processing of the Dead Sea Scrolls was publicized throughout the world on the front pages of newspapers in the spring of 1958. The method for what I called the 'linguistic analysis' of natural texts had t o be tested. (I do not use this expression in any of those specific and fluid meanings which it has in some contemporary fields of the philosophy of language.) A parallel activity was the formation of the Promoting Committee for the IT, listing eminent Italian scholars, and the establishment of a group of friends, professionals and businessmen, into a Finance and Administration Committee. (Among the founders, Emilia and Nino Crespi of Busto Arsizio and Carlo Pensotti of Legnano have already passed away.) Cardinal G.B. Montini accepted the presidency and later Cardinal A. Luciani succeeded him. Was it mere accident that both these men who recognized the value of wedding the old and the new were chosen to be Popes? Two more lines of my activity merged with my daily teaching of philosophy at Gallarate College and the production of the IT. One was the promotion of similar projects in Europe. Up t o the present day I have been active in around 6 0 conferences most of which were international, from Russia t o California and Brazil. Three have been organized and presided over by me: in Tubingen University, November 2426, 1960 (Internationales Kolloquium uber maschinelle Methoden der literarischen Analyse und der Lexikographie); in Pisa, March 27-29; l 9 6 8 (SCmimire intern. sur le Dictionnaire l a t h de Machine); and in Venice, April 27-28, 1979 (Seminario di Lem- 86 JOS RIC THI PHI KA' STE MA1 I. G WAI THE HU( CH1 OK1 THC STA EM1 R01 AN1 HEE BAR PAL DO1 DA\ FRE ROE DA\ WIL HAP HA1 WIN DOI' DOI' DO I CIA Corn scrip currl If nc Subs Ams @N rem'. with R. Busa / The Index Thomisticus matizzazione Computerizzata). In 1967 Professor Antonio Zampolli, up t o then my ,assistant, founded in Pisa the laboratory for computational linguistics which has made him internationally famous. In Tiibingen at the final session the audience wanted me to accept the task of standardizing codes and methods. I refused. "My Big Boss above wanted t o standardize religion. See how He succeeded? Could I expect to be more efficient than He?" Many centers, from Israel to Czechoslovakia, Belgium, France, and Germany, have been inspired by Gallarate Center. Since 1949, I have visited America 35 times. First, I needed to keep in touch with IBM technicians. My second purpose was to exchange ideas with people starting to make use of computers in scientific documentation, soon rebaptized as information retrieval and now as information science. The late Prof. James W. Perry, then at M.I.T. and later at the University of Arizona, the author of many books, introduced me to people, centers, publications and problems of the field. Third, my activities became mixed with those of machine translation, the gold rush which was dampened by the ALPAC report in 1966 that identified the major obstacle to machine translation not as the inadequacy of computer knowledge but rather as our insufficient comprehension of natural language. At that time I associated LCon Dostert's Georgetown Project with the Euratom Center at Ispra, which is a few miles from Gallarate. Thirty years of work In the meantime the operations at Gallarate flowed along without interruption. From 1962 to 1967 we were a team of more than 6 0 full-time participants. Three main tasks were as necessary as they were timeconsuming: pre-editing, lemmatizing, correcting. Various text-typologies had to be identified, codified in the texts, and then properly punched in the sentence-cards. For example, all sentences and single words which the author quoted from other authors had to be specified as such. I still react negatively to those who transfer from a text onto magnetic tape merely the unedited words and the punctuation marks, for in all texts there are features which carry additional information, e.g., those from which a reader understands that here the author quotes ver- batim or summarizes a paragrah of another writer. This information is lost when someone puts into machine-readable form only the words and the punctuation. Our pre-editing demanded scanning all the texts, word by word, at least twice. Associated operations were detecting text printing errors and fixing a system to reference each word t o its location in the text sequence. It was evident, furthermore, that in text of 1 700 000 lines and 1 0 666 000 words, tables and concordances should not represent only non-lemmatized graphic forms of words. Such unspecified information in these quantities would be too bulky and consequently useless. Therefore, a team of ten priests worked with me for two full years to design a Latin machine dictionary. Called the Lexicon Electronicum Latinum (LEL), it is a set of tables by which a computer is able to lernmatize the words of Latin texts. I defined lemrnatizing as two operations: (1) grouping all the forms of an inflected word (e.g., sum, es ... fui, fuisti ... essem, esses, fore, futurus ...) under their 'lemma,' i.e., the title or entry-word which' represents it in a dictionary (here, the verb sum), and (2) coding the morphological categories of each form and lemma. For this, we first punched, sequenced and numbered the 9 0 000 lemmas in the Forcellini's Lexicon Totius Latinitatis (Padua, 1940). Then, we alphabetically sorted all the words of our texts and got a list of 130 000 graphically different forms of words occurring there. We next compared each of these forms with the list of the lemmas. We established in which lemma, either one or several, each of these forms could belong. Finally we defined its morphological categories. In this way, each word-form was examined in isolation from any context; only *its generative possibilities were considered. All problems and aspects of ambiguity (I called it homography) had to be faced and systematized. As the computer demands full systematicity and absolute fullness, we had to reorganize Latin grammar and the Latin lexicon. This operation entailed tracing the borders between the morphological and the syntactical; the distinction between adjectives and nouns, for example, appeared without doubt to be syntactical. It varies, in fact, according to different contexts. Thus a lexicon should provide this category as inducted statistically from the uses of the word or as following semantic R.Busa l T h e Index Thornisticus er. It0 1C- the raga the in le S mied ky :en na roha tin ns: )rd re, or re, ~ch .ed ius lly of urms ich ms cal led ive nd to lds to his .he on .ed ct, on UY tic preclusions. At least in Latin, however, no morpheme in the structure of a word ever differentiates an adjective from a noun. The LEL now contains 150000 Latin forms fully lemmatized and lemmatizing. When applied to any other Latin text it will signal the forms which it does not possess. The proceedings of the Pisa Seminar (Revue [LiCge, 1969, pp. 1-176) record the features which differentiate my 'morphological' Latin dictionary from the 'syntactical' one developed at LiCge by Prof. L. Delatte, which lemrnatizes every occurrence of a word in its contest. The ten fields of my morphological codes plus the four fields of homography codes of my LEL could be defective, but if so, only in the line of too much and not of too little. I had completed the keypunching of all my texts before the opportunity of correcting texts on tape at a video-terminal existed. Less than 20% of the time was spent on the first punching and more than 80% on cleaning the input. Verifying all the text-cards on a verifier, we corrected the errors and then listed the corrected cards. In teams of two, we checked the list by reading it against the text. Then we repeated the process by listing, checking and correcting everything again. Even after these three checks, however, we still discovered 1600 punching errors and one full line lost because of an homoteleuton. The ratio of human work t o machine time was more than 100 : 1. Computer hours were less than 10000 while man hours were much more than one million. In fact we had to scan our texts word by word with human eyes and fingers at least 9 times: twice for pre-editing; once for punching; once for verifying; twice (two people each) for checking; twice for lemmatizing and sorting the homographs; and once for final arrangements and checkings. All this would be about equal to scanning 95 000000 separate words. That means that in 25 years we processed an average of 2200 words per working hour or 4 lines of text per minute. I imagine that a similar quantity of text could be processed today in ten or even six years, using video terminals and optical character recognition. But then I had to solve problems which no longer exist today. Without assistance and in addition to fmding financial support, I had to develop and test a method which had no predecessor and had to use a technology which developed progressively. 87 Retrospective criticism I was never trapped in a major cul de sac or distracted by a major U-turn. Nevertheless I realize already three defects in my procedures. First, as we processed the reference as a field in each line- and word-record, it would have been more practical to have the reference as a record in itself and to develop it automatically into each word reference only after the final text corrections: we could have avoided needing to correct the referencing of all the following words when adding or deleting a word. Then, in the Concordantia Prima, we sorted the key-words according to the contiguous following word only when it was one of those having a grammatical or connective function. It would have been more useful, in sorting each key-word, to attach to it any type of following word (obviously with no major punctuation between), as D.W. Packard did in his Livy concordance. Finally, in the Concordantia Altera all trinomiums having the same words were sorted first by speech typologies and then by their punctuation marks. It would have been better to do vice versa, i.e., to sort them first by punctuation and then by speech typology. Were I to begin a similar project today, however, I would process it the same way. After 3 0 years of research I am still convinced that: pre-editing and lemmatizing are necessary in processing large texts; an important scientific role is played by processing of function and high-frequency words (pronouns, et, non, sum, etc.); this was almost never done previously because it is infeasible manually, but it is practical using a computer; adding summary tables with quantitative information to concordances provides so valid a research tool that I cannot see any good reason for omitting it. I was able to complete my IT 33 years after the conception of the project and 3 0 years after my first meeting with IBM. At that time it was the first undertaking in computer linguistics. Even today it is the only published work of its kind with such dimensions and such characteristics. I feel like a tight-rope walker who has reached the other end. It seems to me like Providence. Since man is child of God and technology is child of man, I think that God regards technology 88 JOS RIC THI PHI KA' STE MA1 I. G WAI THE HU( CHd OK1 THC STA EM1 R01 AN1 HED BAR PAL DO1 D A\ FRE ROE D A\ WIL HAE HAI WIN DOP DOP DOI GIA Subs Ams @N retri with Sub! sum; cop: 191; R. Busa / The Index Thornisticus the way a grandfather regards his grandchild. And for me personally it is satisfying to realize that I have taken seriously my service to linguistic research. Anyone comparing the typographical quality of the IT with offset computer printouts will understand why I am now happy that I did not complete the project before photocomposition was available. Before publishing the IT in book form, we'debated publishing it on microfiche or simply keeping it available in a data bank. Since half of the 500 printed copies were sold in two years, it is clear that we made the right decision. Research with books or on a computer terminal should not yet be considered alternative but rather complementary. In most cases only printed volumes can provide the information necessary for computer-aided research, and very often one can locate in a few seconds in the printed volumes information whch would require the scanning of 10 million records if it were to be located on tapes. The computerization of language in its present state: a personal reflection In sketching the status artis in the electronic processing of language, spoken language and written language must first be distinguished. By processing spoken language I mean speech synthesis and speech analysis, which is much more than recording, transmitting, reproducing the human voice. The techniques by which the computer has a human voice as its output have already surpassed the laboratory phase. In speech analysis a computer has a human voice as its input, as in dictation to a Typewriter. These techniques-are still caught in slow and laborious laboratory research, Written language has to be divided into handwritten and printed texts. Here, too, input and output must be distinguished. Post offices are extremely interested in a computer that would read any kind of handwriting. It seems that, altogether, these techniques have not gotten beyond the research stage. In any case, an electronic deciphering of ancient manuscripts would be science fiction. The electronic reading of typed texts, on the other hand, whenever all letters are inscribed in identical spaces, has been in practical use for many years already. But only since a few years ago has the tech- nique. been perfected for reading a printed text where the letter spaces are unequal. As for electronic printing, the 70000 photocomposed pages of my IT bear witness that today it offers no fewer output possibilities and qualities than manual or hot typesetting. Concerning the status artis of the procedures themselves, I need to distinguish two kinds of 'words': on one hand, all digits, any other system of symbols (e.g., musical notes or codings for archeological findings) and, surprisingly enough, proper names; on the other, those words which we commonly call words. The processing of digits and symbols by computer in mathematics, sciences, documentation and all business has reached gigantic proportions. Today's technological explosion is based upon it. The computer processing of those words which we commonly call words, however, has not yet developed beyond the first meager steps. We must not hide the fact that the compiling of tables, indices and concordances of individual words, including their correlations, though so necessary for philology and lexicography, is conceptually a somewhat feeble result, still very far from practical applications. We shall have an information industry in the full sense of the term only when we have computer programs performing indexing and abstracting operations. The major obstacle lies in the 'semanticity' of 'words,' which is deeply different from that of numbers and symbols. There is a multiple diversity; only in words, for instance, is metaphor possible. Furthermore, we do not speak in words but in sentences. A sentence has a global meaning which is not the pure sum of the values of its single components. The heart of this problem is whether or not we are able to formalize the global meaning of sentences with something less than the whole sentence itself; in other words, whether or not we can succeed in identifying in each sentence something which can be taken as characteristic of its global meaning. I am not sure whether artificial intelligence will eventually solve this problem. Computerization provides humanities with new qualitative dimensions The use of computers in linguistic analysis is first of all very different from scientific computation: the R. Busa i / The Index latter has comparatively little input. little output, huge processing; the former has huge input, huge output, comparatively little processing. One could say that our job is similar to computerizing bank accounts, but there is still a tremendous difference: bank processings are repetitive functions, while in linguistic research, precisely because it is research, most of the programs are used only once, for the phase for which they have been designed; the following phase will demand a new and different program. In other fields, the computer is used to give those who have to make decisions about events a summary of a flow of those events as they take place. In these cases the computer should be as close as possible to be contemporaneous with the events. In computerizing linguistic analysis there is obviously no such urgency. In this field one should not use the computer primarily for speeding up the operation, nor for minimizing the work of the researchers. It would not be reasonable to use the computer just to obtain the same results as before, having the same qualities as before, but more rapidly and with less human effort. Imagine a research project which without the computer would require a man to work one year: in my opinion it would not be the optimal use of the computer to complete the same research in a month. But the optimal and specific use of the computer would be for two years on a research project one thousand times larger and one hundred times more profound, aiming at results which would be unobtainable without it. During these two years the researcher's work will not be diminished but rather increased, yet concentrated in those higher levels of analytic and creative functions whlch are the prerogative of the human mind. To repeat: the use of computers in the humanities has as its principal aim the enhancement of the quality, depth and extension of research and not merely the lessening of human effort and time. In fact, the computer has even improved the quality of methods in philological analysis, because its brute physical rigidity demands full accuracy, full completeness, full systematicity. Using computers I had to realize that our previous knowledge of human language was too often incomplete and anyway not sufficient for a computer program. Using computers will therefore lead us to a more profound and systematic knowledge of human expression; in principle, it can help us to be more humanistic than before. Thornisticus There is another reason for saying this: insofar as linguistic research attacks the semantic content of the words, sampling is no longer sufficient. Whereas it can be a valid method, in phonetics, for example, it cannot be in lexicography. Linguistic research must tend to be based on full inventories of words at least of large corpuses. Semantics is the description of the kingdom of the creative freedom of spirit: in man it is his soul which talks. Consequently scientific description of how we talk can be nothing but probabilistic. Today's academic life seems t o be more in favor of many short-term research projects which need to be published quickly, rather than of projects requiring teams of co-workers collaborating for decades. But, going back t o what I have just said, to put into practice the electronic processing of human sentences as such, much more induction is needed. The magnificent store of mathematical methods we have today has to be based on linguistic censuses of natural texts of millions of words. Sometimes a splendid amount of mathematics is applied to too small a base of linguistic data. It would be much better to build up results one centimetre at a time on a base one kilometre wide, than to build up a kilometre of research on a one-centimetre base. The human factor in the computerization process A few final notes on the type of human work required. In terms of time, the most demanding phase has been the preparation of the input. Only a few organizing decisions have been conceptually complex and difficult. Most of the human operations were simple but had to be repeated over and over again tens of thousands of times. Particular attention was given to the necessity of being consistently inductive and analytical; that is to say, ready to recognize only those categories effectively emerging from the data. In other words, we endeavored to avoid forcing the data into preformulated or imaginary a priori categories. The computer has been a great help in this process, as it allowed us to check the validity of our categories on the full inventories of all involved data. Other aspects of human commitment required in this project were those Comnon to any teamwork, yet two were given special care. The first was utmost attention to every minimal detail. A dogma was that 90 JOS RIC THI PHI KA' STE MA1 I. G WAI THI HU( CH) OK1 TH( STA EM1 R01 AN'I HE1 BAN PAL DO I DA\ FRE ROE DA\ WIL HA? HAF WIN DOP DOP DO 1 CIA scrip CUIIi If nc Sub! Ams re trz. with Sub1 sum, COP. 191; R. Busa / The Index no one should allow himself, or allow any other person, to overlook an error or a defect or a doubt on the assumption that it was a small one and seemingly of no importance. No one can afford to ignore even a single loose screw in a machine or the entire works may fail. The second was the need to armor oneself with inexhaustible patience and perseverance to cope Thornisticus with snags, accidents, machine failures, errors and ur foreseen events, which have rendered linguistic ana ysis very similar to an obstacle race. That is the reason why the use of computers i linguistics demands a lot of dedication and har work. Without them, computers would only produc 'in real time' monuments of waste.