The Washington Post John Philip Sousa

advertisement

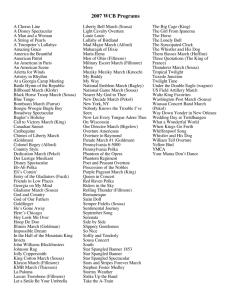

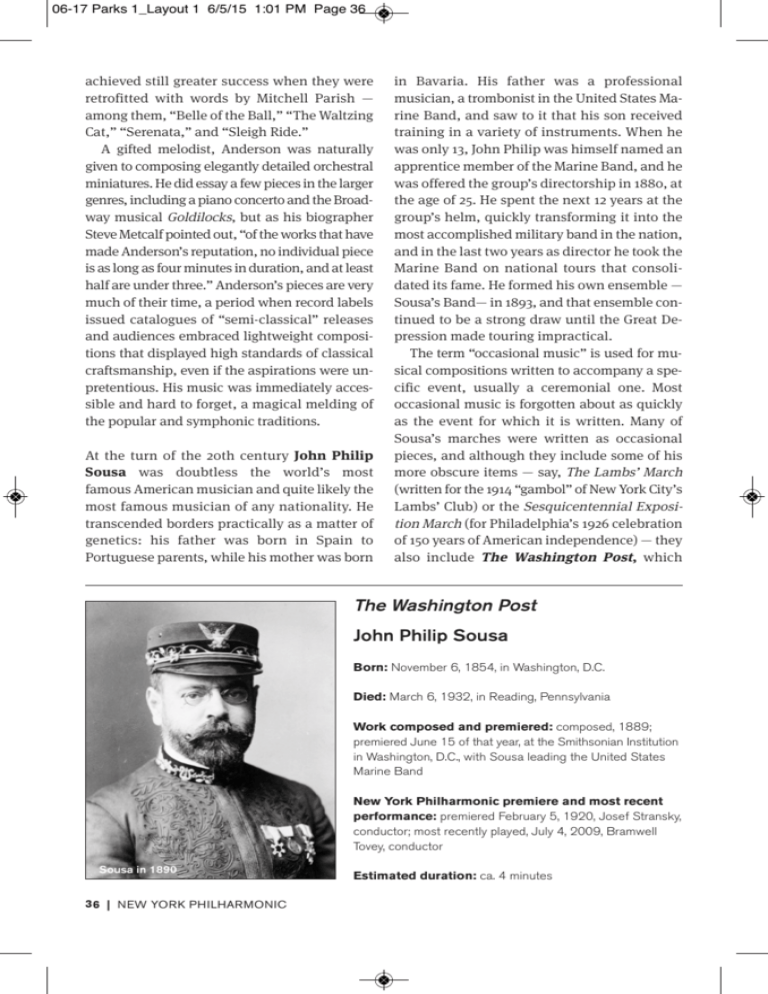

06-17 Parks 1_Layout 1 6/5/15 1:01 PM Page 36 achieved still greater success when they were retrofitted with words by Mitchell Parish — among them, “Belle of the Ball,” “The Waltzing Cat,” “Serenata,” and “Sleigh Ride.” A gifted melodist, Anderson was naturally given to composing elegantly detailed orchestral miniatures. He did essay a few pieces in the larger genres, including a piano concerto and the Broadway musical Goldilocks, but as his biographer Steve Metcalf pointed out, “of the works that have made Anderson’s reputation, no individual piece is as long as four minutes in duration, and at least half are under three.” Anderson’s pieces are very much of their time, a period when record labels issued catalogues of “semi-classical” releases and audiences embraced lightweight compositions that displayed high standards of classical craftsmanship, even if the aspirations were unpretentious. His music was immediately accessible and hard to forget, a magical melding of the popular and symphonic traditions. At the turn of the 20th century John Philip Sousa was doubtless the world’s most famous American musician and quite likely the most famous musician of any nationality. He transcended borders practically as a matter of genetics: his father was born in Spain to Portuguese parents, while his mother was born in Bavaria. His father was a professional musician, a trombonist in the United States Marine Band, and saw to it that his son received training in a variety of instruments. When he was only 13, John Philip was himself named an apprentice member of the Marine Band, and he was offered the group’s directorship in 1880, at the age of 25. He spent the next 12 years at the group’s helm, quickly transforming it into the most accomplished military band in the nation, and in the last two years as director he took the Marine Band on national tours that consolidated its fame. He formed his own ensemble — Sousa’s Band— in 1893, and that ensemble continued to be a strong draw until the Great Depression made touring impractical. The term “occasional music” is used for musical compositions written to accompany a specific event, usually a ceremonial one. Most occasional music is forgotten about as quickly as the event for which it is written. Many of Sousa’s marches were written as occasional pieces, and although they include some of his more obscure items — say, The Lambs’ March (written for the 1914 “gambol” of New York City’s Lambs’ Club) or the Sesquicentennial Exposition March (for Philadelphia’s 1926 celebration of 150 years of American independence) — they also include The Washington Post, which The Washington Post John Philip Sousa Born: November 6, 1854, in Washington, D.C. Died: March 6, 1932, in Reading, Pennsylvania Work composed and premiered: composed, 1889; premiered June 15 of that year, at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., with Sousa leading the United States Marine Band New York Philharmonic premiere and most recent performance: premiered February 5, 1920, Josef Stransky, conductor; most recently played, July 4, 2009, Bramwell Tovey, conductor Sousa in 1890 36 | NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC Estimated duration: ca. 4 minutes 06-17 Parks 1_Layout 1 6/5/15 1:01 PM Page 37 probably ranks as the second most popular of his 136 marches, trailing only The Stars and Stripes Forever. The Washington Post newspaper had been founded in 1877 as a four-page “Democratic daily journal.” In 1889 the paper sponsored an essay contest for public school students, an incentive it unveiled under the name Amateur Authors Association. Sousa and the U.S. Marine Band were enlisted to play at the awards ceremony, which was to be held at the Smithsonian Institution on June 15, 1889. In the run-up to the event, the Post’s co-publisher, Frank Hatton, asked Sousa to consider writing a new march for the occasion, and the band leader consented, dedicating his new work to — and in fact naming it for — the newspaper itself. Although marches are typically thought of as being in simple-duple time (2/4 or 4/4 meter), they can just as easily be written in a more skipping compound-duple meter (usually 6/8). The Washington Post is of the latter variety, and the piece owes a good measure of its popularity to the fact that marches in 6/8 time were at that moment being pressed into use for the newly devised social dance called the two-step. In fact, The Washington Post became the prototypical two-step, which made it an instant international hit for both parade grounds and ballrooms. Notwithstanding its tremendous success, this march did practically nothing to enrich its composer. As with all his early marches, Sousa had sold this one outright to his publisher — in this case for $35. Not until he produced his march The Liberty Bell, in 1893, would Sousa strike a publishing deal that would ensure him ongoing royalties. In the Composer’s Words In his autobiography, Marching Along (1928), John Philip Sousa wrote (perhaps with a touch of geographical imprecision) of how inescapable The Washington Post had become: I have smiled almost incredulously many a time at proofs of the world popularity of that march. It seems there is no getting away from it — even in the fastnesses of a Borneo jungle! Major Coffin of the Army, told me that one day as he was walking through a forest in Borneo he heard the familiar sound of a violin and suddenly came upon a little Filipino boy, with his sheet music pinned to a tree, diligently working away on The Washington Post. As for more conventional places, the wildfire spread with even greater vigor. When I went to Europe I found that the two-step was called a “Washington Post” in England and Germany, and no concert I gave in Europe was complete without the performance of that march. It was the rage, too, in staid New England, for an orchestra leader in a New England town declared that, at one ball, the only obstacle to his playing the thing twenty-three times was the fact that there were only twenty-two dances on the programme. Even during the recent World War its cadences clung. One of our soldiers told me that he had stopped for a drink of water at a little house in a French village and the old peasant who came to the door invited him in and, learning that he was an American, immediately commanded his little girl to play some American music for the guest. The child obliged — with The Washington Post. The “Washington Post” two-step JUNE 2015 | 37