1 JOHN KEATS LETTERS (1817-1818) Letter to Benjamin Bailey

advertisement

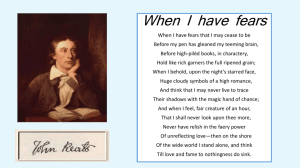

Richard L. W. Clarke LITS2002 Notes 10 1 JOHN KEATS LETTERS (1817-1818) Letter to Benjamin Bailey, November 22, 1817 “I wish you knew all that I think about the about Genius and the Heart” (301):“Men of Genius are great as certain ethereal Chemicals operating on the Mass of neutral intellect” (301). They “have not any individuality, any determined Character” (301-302). Arguing that this is a subject that he knows little about and which deserves much greater study, Keats turns his attention to the “authenticity of the Imagination” (302). “I am certain of nothing but of the holiness of the Heart’s affections and the truth of Imagination – What the imagination seizes as Beauty must be truth” (302). (See “Ode on a Grecian Urn” where he utters the famous phrase: “‘Beauty is truth, truth beauty’–that is all / Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know” [ll. 48-9].) The “Imagination may be compared to Adam’s dream – he awoke and found it truth” (302). “I have never yet been able to perceive how any thing can be known for truth by consecutive reasoning - and yet it must be - Can it be that even the greatest philosopher ever arrived at his goal without putting numerous objections” (302). “O for a Life of Sensations rather than of Thoughts!” (302). Praising those who “delight in sensation rather than hunger . . . after Truth” (302), Keats argues that “Imagination and its empyreal reflection is the same as human Life and its spiritual repetition” (302). The “simple imaginative Mind may have its rewards in the repetition of its own silent Working coming continually on the spirit with a fine suddenness” (302): have you never by being surprised with an old Melody . . . by a delicious voice, felt over again your very speculations and surmises at the time it first operated on your soul – do you not remember forming to yourself the singer’s face more beautiful than it was possible and yet with the elevation of the Moment you did not think so – even then you were mounted n the Wings of Imagination so high. . . . Sure this cannot be exactly the case with a complex Mind – one that is imaginative and at the same time careful of its fruits – who would exist partly on sensation partly on thought – to whom it is necessary that years should bring the philosophic Mind. (302-303) “The world is full of troubles and I have not much reason to think myself pestered with many . . . for really I do not think of my brother’s illness connected with mine” (303). “I scarcely remember counting upon any Happiness – I look not for it if it be not in the present hour – nothing startles me beyond the Moment” (303). Keats writes that I become “a part of all I see” (303): “if a sparrow come before my window I take part in its existence [sic] and pick about the gravel” (303). Letter to George and Thomas Keats, December 21, 1817 “The excellence of every art is its intensity, capable of making all disagreeables evaporate, from their being in close relationship with beauty and truth. Examine King Lear and you will find this exemplified throughout” (304). In bad art, however, you “have unpleasantness without any momentous depth of speculation excited, in which to bury its repulsiveness” (304). Richard L. W. Clarke LITS2002 Notes 10 2 What Keats terms “negative capability” (305) (what he calls elsewhere “Humility and the capability of submission” [301]) is a “quality” (305) characteristic of the greatest writers and “which Shakespeare possessed so enormously” (305). It is “when man is capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason” (305). Keats argues that “with a great poet the sense of beauty overcomes every other consideration, or rather obliterates all consideration” (305). Letter to J. H. Reynolds, February 19, 1818 “When Man has arrived at a certain ripeness in intellect any one grand and spiritual passage serves him as a starting point towards all ‘the two and thirty Pallaces.’ How happy is such a ‘voyage of conception,’ what delicious diligent indolence” (305). The “honors paid by Man to Man are trifles in comparison to the Benefit done by great Works to the ‘Spirit and pulse of good’ by their mere passive existence” (305-306). Memory should not be called knowledge – Many have original Minds who do not think it – they are led away by Custom – Now it appears to me that almost any Man may like the Spider spin from his own inwards his own airy Citadel – the points of leaves and twigs on which the Spider begins her work are few and she fills the Air with a beautiful circuiting: man should be content with as few points to tip with the fine Webb of his Soul and weave a tapestry empyrean – full of Symbols for his spiritual eye. . . . (306) But the Minds of Mortals are so different and bent on such diverse journeys that it may at first appear impossible for any common taste or fellowship to exist between two or three under these suppositions – It is however quite the contrary – Minds would leave each other in contrary directions, traverse each other in Numberless points, and all last greet each other at the Journeys end. . . . Man should not dispute or assert but whisper results to his neighbour, and thus by every germ of Spirit sucking the Sap from mould ethereal every human might become great, and Humanity instead of being a wide heath of Furse and Briars with here and there a remote Oak or Pine, would become a grand democracy of Forest Trees. (306) [I]t seems to me that we should rather be the flower than the Bee. . . . Now it is more noble to sit like Jove than to fly like Mercury – let us not therefore go hurrying about and collecting honey-bee like, buzzing here and there impatiently from a knowledge of what is to be arrived at: but let us open our leaves like a flower and be passive and receptive--budding patiently under the eye of Apollo and taking hints from every noble insect that favours us with a visit – sap will be given us for Meat and dew for drink. (306) Keats says that he “was led into these thoughts . . . by the beauty of the morning operating on a sense of Idleness – I have not read any Books – the Morning said I was right – I had no Idea but of the Morning and the Thrush said I was right” (306). Letter to John Taylor, February 27, 1818 (from Critical Theory Since Plato, ed. Hazard Adams) Here, Keats offers a few “axioms” (494) about poetry: Richard L. W. Clarke LITS2002 Notes 10 3 I think poetry should surprise by a fine excess and not by singularity – it should strike the reader as a wording of his own highest thoughts and appear almost a remembrance – Second, its touches of beauty should never be halfway thereby making the reader breathless instead of content: the rise, the progress, the setting of imagery should like the sun come natural to him – shine over him and set soberly although in magnificence, leaving him in the luxury of twilight – but it is easier to think what poetry should be than to write it. . . . (494) Keats concludes: “if poetry comes not as naturally as the leaves to a tree it had better not come at all” (494). Letter to Richard Woodhouse, October 27, 1818 Here, Keats offers “some observations . . .about genius” (307): As to the poetical Character itself (I mean that spirit of which, if I am anything, I am a Member; that sort distinguished from the wordsworthian egotistical sublime; which is a thing per se and stands alone) it is not itself – it has no self – it is everything and nothing – It has no character – it enjoys light and shade; it lives in gusto, be it foul or fair, high or low, rich or poor, mean or elevated – It has as much delight in conceiving an Iago as an Imogen. What shocks the virtuous philosopher, delights the camelion Poet. It does no harm from its relish of the dark side of things any more than from its taste for the bright one; because they both end in speculation. A Poet is the most unpoetical of any thing in existence; because he has no Identity – he is continually in for – and filling some other body – The Sun, the Moon, the Sea and Men and Women who are creatures of impulse are poetical and have about them an unchangeable attribute – the poet has none; no identity – he is certainly the most unpoetical of all God’s Creatures. . . . It is a wretched thing to confess but: but is a very fact not one word I ever utter can be taken for granted as an opinion growing out of my identical nature – how can it, when I have no nature? When I am in a room with People . . . then not myself goes home to myself: but the identity of everyone in the room begins [to] press upon me [so] that, I am in a very little time annihilated. . . . [E]ven now I am perhaps not speaking from myself; but from some character in whose soul I now live. (307-308) I am ambitious of doing the world some good: if I should be spared that may be the work of maturer years – in the interval I will assay to reach as high a summit in Poetry as the nerve bestowed upon me will suffer. The faint conceptions I have of Poems to come brings the blood frequently into my forehead – All I hope is that I may not lose all interest in human affairs – that the solitary indifference I feel for applause even from the finest Spirits, will not blunt any acuteness of vision I may have. I do not think it will – I feel assured I should write from the mere yearning and fondness I have for the Beautiful even if my night’s labours should be burnt every morning and no eye ever shine upon them. (308)