Chapter 4 Family Planning

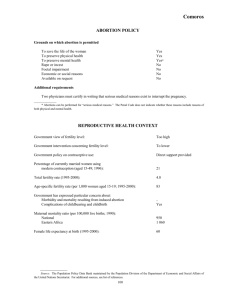

advertisement