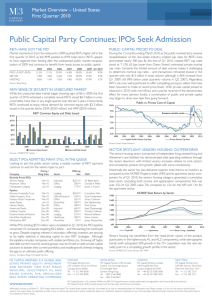

Effectsof Regulatory and Market Constraints on the Capital Structure

advertisement