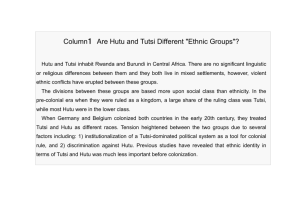

4. Rwanda - The University of Michigan Press

advertisement