The Historical and Linguistic Analysis of Turkish Politicians' Speech

advertisement

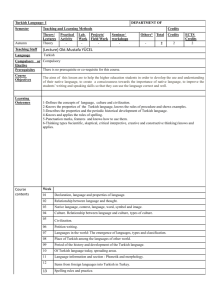

Int J Polit Cult Soc DOI 10.1007/s10767-010-9103-7 The Historical and Linguistic Analysis of Turkish Politicians’ Speech Baburhan Uzum & Melike Uzum # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2010 Abstract The current study investigates Turkish politicians’ code mixing in their public speeches and the variation among the speakers as well as the historical and linguistic factors influencing this variation. It is hypothesized that the variation either consciously or unconsciously outlines the identity of the speaker in the direction that s/he wants to be identified by their audience. The findings are interpreted with reference to the language reform (a linguistic change during the transition from the Ottoman Empire to the Turkish Republic) that Turkish language went through in 1928. Keywords Linguistic reform . Politics of language . Identity transformation . Speech analysis . Language change Introduction In order to shed light onto the use of contemporary Turkish, it is obligatory to investigate the historical and sociopolitical factors that paved the way for the language reform. After the collapse of the Ottoman Empire during the First World War in 1918, the Turkish Republic was founded in 1923. The Ottoman Empire, being the home of numerous ethnicities for more than 600 years, did not have a strict language policy and granted the public the independence to speak the language they chose. In the nineteenth century, there was an enormous discrepancy among the citizens of the empire. While minorities used their heritage language, the majority of Turkish people used Turkish, and the Ottoman language was confined within the walls of the palace spoken only by the elite. Ottoman language was heavily influenced by Arabic and Persian due to their prestigious status at the time. Aydıngun and Aydıngun (2004) maintain that the language reform was imperative to B. Uzum (*) Second Language Studies, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48823, USA e-mail: baburhan@msu.edu M. Uzum Turk Dili ve Edebiyati, Konya Selcuk Universitesi, Meram, Konya, Turkey Uzum and Uzum maintain the unity of the empire which had been invaded by the greatest powers of Europe. In order to diminish this discrepancy and unite the people of the infant republic with a common ideal, Turkish Language Reform was adopted in 1928. It is interesting to note that Turkish language was not a prestigious language either in the Seljuq Dynasty (before the Ottoman Empire) or the Ottoman Empire. The Seljuq dynasty greatly admired Persian for being the language of science and literature during the eleventh and twelfth centuries, while the Ottoman Empire attributed much prestige to Arabic for the language of Quran and Islam. Turkish language, formerly being perceived as a nomad language, was chosen to be the language of the Republic. In addition to the language, “Turk” was the new identity of the public. In order to refute the old beliefs about Turkish language and Turkish identity and build a nation from its ashes, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk—the founder of the Republic —emphasized the significance of the language in his speeches. Bear (1985) quotes Ataturk: The language of the Turkish nation is Turkish. The Turkish language is the most beautiful, the richest and the simplest language in the world. For that reason, every Turk loves his language greatly and seeks to glorify it. Furthermore, the Turkish language is a sacred treasure for the Turkish nation. Because, the Turkish nation realizes that in the many difficult situations which it has experienced, it has preserved its morals, its traditions, its memories, its interests, in short, everything which makes up its own nationality through the medium of the language. Turkish language reform, promoted by Ataturk with the goal of rescuing Turkish from the influence of other languages such as Ottoman, Persian, and Arabic, included the process of purification. This involved excluding non-Turkish words from its lexicon, replacing these with Turkish words, coining new words from Turkish roots and affixes and adopting the Latin alphabet. However, the course of years that followed brought about new sociopolitical changes causing, some social and linguistic problems to emerge. First of all, nationalism which was originally promoted for nation-building purposes was often associated with racism and ethnocentrism. Ultimately, two extreme theories emerged in the 1930s, over-emphasizing the Turkish identity. These two theories are “the sun-language theory” and “Turkish history thesis.” According to the former, Turkish language had been the most ancient language, and it had provided crucial elements for the creation of other languages (Ayturk, 2004). Turkish history thesis, on the other hand, claims that all nations within Anatolia were of Turkish origin as the people who came from the central Asia were the first residents of the region. Neither of these theories could be supported by scientific evidence; however, they were suggested with the aim of increasing pride in Turkish culture so that Turkish people could claim a respected status in the world history. In addition to the nationalism boosted by these theories, some other problems emerged in the following years due to modernization and westernization. In the 1920s, Ataturk aimed to create a Turkish identity escorted by modernization. The Ottoman Empire had fallen behind other European countries in terms of military, social, and educational improvements. During the speedy transformation, social, political, and educational reforms brought linguistic influences. New concepts were adopted along with their foreign lexicon. French, the lingua franca of the time, penetrated into the Turkish language through such concepts. As the process of modernization brought along its vocabulary, Turkish language was, yet again, under the massive influence of foreign languages. Özen (2003) put his disagreement with the following quotation: Once Arabic and Persian, and then French, in the age of modernization and the Westernization. Everything in the country became ‘German’, including Wilhelm style The Historical and Linguistic Analysis of Turkish Politician Moustache. When train came into the country, it came along with cars filled with French words! Imagine, anything pertinent to trains in this country is not Turkish! Do Germans do that? There was only Atatürk who wanted to lead this train into national lands, and achieved this in his time The current statistics show that Turkish language was heavily influenced from the process of modernization. Modern Turkish Dictionary (2005) includes 104,481 entries, of which about 14% are of foreign origin. Among the word donors, Arabic comes first with 6,463 words followed by French (4,974), Persian (1,374), Italian (632), English (538), and Greek (399). As a result of Turkish Language Reform, Persian and Arabic lost their dominance in the lexicon of the contemporary Turkish language; yet, other European languages penetrated in to the language with the process of modernization. In the contemporary Turkey of the 2000s, the influences of language reform and the subsequent social and linguistic changes could still be observed in language use. Given that speech is always subject to variation and otherwise interpersonal communication would not be possible (Williams 1992), Turkish language along with its history and politics is allowing much room for variation. Thanks to the contributions of different languages to Turkish lexicon, speakers enjoy the independence to switch to different codes or borrow words from different codes depending on their education, political orientation, or background. To clarify, a speaker who identifies himself with the religion Islam may tend to borrow words from Ottoman, Arabic, and Persian, while another speaker, identifying himself with the Turkish identity, follows a more nationalist approach and do not use any borrowed words being loyal to the pure Turkish lexicon. Finally, a speaker believing modernization and westernization thus keeping himself away from both Islamic conservatism and Turkish nationalism tends to borrow words from European languages. To illustrate, to mean “specific,” the first speaker says “mustesna,” the second “ozel,” and the latter “spesifik.” The frequency and the contexts of their lexical choices might be revealing their social identity, political orientation, and educational background. Related Studies Having a similar focus to the current study, the study of Amara (1996) investigated the lexical borrowings from English and Hebrew in Palestinian Arabic. Exploring how social and political pressures are related to the pattern of sociolinguistic change in a speech community, he concluded that language contact with Hebrew speakers triggered an effect on Palestinian Arabic due to its prestigious status stemming from the association of Israeli culture with progress. Studies investigating identity (re)-construction have significant relevance to the current study. Amara and Spolsky (1996) carried out a noteworthy study exploring the construction of identity in a divided Palestinian village. They conducted a sociolinguistic survey of a village for 2 years. A total of 81 villagers were interviewed and recorded creating contexts for careful and more informal speech. They concluded that the construction of Israeli identity is through some borrowed qualities. The Arab–Palestinian identity, on the other hand, encourages standard Arabic features. According to the findings of Amara and Spolsky, the most influential identity is Palestinian, probably due to the linguistic change towards Standard Arabic and the major sensitivity to its use. Another study, investigating Turkish language as a symbol of survival and as an identity marker in the Balkans and in Turkey, was carried out by Balim in 1996. Balim (1996) Uzum and Uzum provided a brief history of the current situation and wrote of the resistance of Turkish people living in the Balkans, before they were forced to migrate to Turkey by the Bulgarian government in the 1950s. As for the language policies in Turkey, there is also a considerable effort to prevent foreignization by translating words and terms of foreign origin and thus make new Turkish words. For example: sabun operası—the direct translation of “soap opera”; doğalgaz—“natural gas”; masaüstü yayıncılık—“desktop publishing.” Reporting the recent attempts of Turkish government to control the penetration of foreign words into Turkish, she concluded that the language to be used can no longer be regulated by law or by government decree. It is the younger generations who will determine the pattern of use. Abu Haidar (1996) had a similar scope to the current study using the opposite direction. Recording the Baghdadi speakers from different ages in England, he studied the Turkish borrowings in the respondents’ speech. According to his research findings, the lexical items found in their speech were mostly (1) substantives (such “fault,” etc.), adjectives (mawi “blue”), and particles (ham “also,” balki “perhaps”). He concluded that Turkish and Baghadi Arabic communities showed a significant similarity in the way they regard Turkish, as a symbol of their ethnoreligious identity. Though Turkish borrowings are decreasing through generations, they continue to be used due to their symbolic value. In addition to the emphasis on religious affiliation, Turkish borrowings create an in-group code encouraging group solidarity and identity in the face of increasing interference from other varieties of Arabic. As for the major events in the history of Turkey that brought about sociolinguistic changes, Turkish Language Reform has a major role. One of the earliest studies exploring the effects of Turkish Language Reform on individual perception is that of Cuceoglu and Slobin (1980). In this study, they investigated the attitudes of the audience towards the speakers with varying frequencies of different codes. They found that learners were able to identify the speakers as leftist and rightist, evaluating their speech, and thus favor or dismiss them depending on their own political orientation. On the other hand, the claim of this study for an imaginary or a third space through code-switching was also reflected in a recent study by Bhatt (2008) which investigated the use of Hindi in English newspapers in India. In this study, he argues that code-switching creates a third space where two systems of identity reflection come together in response to global/local tensions and identities formed through resistance and appropriation. He concludes that speakers in this space have the capability to synthesize and to transform. Therefore, code-switching serves as a marker of this transformation, the inventive adaptation to communicate a kind of multiplicity which is highly contextual and a new “habitus” for its speakers with a slightly changed representation of social order. Method The current study hypothesizes that the politicians’ lexical choice is not arbitrary and may follow a pattern because of conscious or unconscious choices they make between the languages. The data for this study come from unplanned public speeches made by the politicians belonging to different parties from September 2006 and July 2007 during the election campaigns that happened in Turkey. The sampled parties are (1) AKP and (2) SP (Islamic-conservative groups-right wing), (3) MHP and (4) BBP (Turkish nationalist groups-right wing), and (5) CHP and (6) DSP (secular-modernist groups-left wing). One or two speakers will be selected from each party. The reason for selecting politicians are (1) the parties they are from represent the group they belong to, so that they will be associated The Historical and Linguistic Analysis of Turkish Politician to a social group in the society, (2) if there is a conscious effort to choose a code, this must be most marked in their case as they would like to be perceived in a certain way by their interlocutors, (3) the data they provide are publicly available and share similar contexts among the speakers including topics formality and interlocutors. Data Analysis The public speeches are transcribed and coded for analysis. A coding scheme, including the structure of the borrowed word (noun, verb, etc.), the origin of the borrowed word (Arabic, English, Persian) the preceding and following words, the position in the sentence, the context of utterance, the topic of utterance (law, education, etc.), the frequency of the word in this data set, stress, and phonological variation (following and preceding pause) is created. According to the preliminary analysis of the coding scheme, token words are selected for in-depth analysis. The findings are interpreted using quantitative and qualitative analysis (content analysis) methods. For qualitative analysis, the frame of reference of Johnstone (2000) is used for design and methodology issues. Some tokens which have political meanings (democracy, republic, election) and are used without variation among all the speakers, are excluded from analysis. Results and Discussion According to the statistical findings, the speakers did online borrowings from other languages including Arabic, Persian, French, English, etc. during the elapsed time of their speech. In order to investigate which speaker refers to which language for borrowing a word, variable rule analysis has been conducted. The distribution of borrowings according to the languages and the speakers are investigated within the framework of eight factors which are shown in Table 1. According to the variable rule analysis: Binominal up and down (which is a logistic regression test identifying the factor groups contributing to the model, and eliminating those without any significant contribution), factors 2–8 were eliminated and factor 1, part of the speech, was identified to be the only factor with most contribution (likelihood=−139.048, p<0.05). In addition to the binominal up and down test, descriptive analyses are used to show the differences between the variables, which might have an influence on the dependent variable not yet statistically large enough to be detected by the logistic regression tests. Figure 1 shows the scatter gram for probability of influence. The descriptive analysis of the factors is given in the order they have appeared in Table 1. According to the statistical findings, the percentage of the speakers’ use of borrowed words is 41.2% (N=93), while the use of Turkish-origin words has a percentage of 58.8% (N=133). Table 2 illustrates the percentage and frequency of borrowed and Turkish-origin words within this data set. An example of the use of Turkish words is given in sentence (1), and an example of the use of borrowed words is given in sentence (2) below: 1. Bu ne anlama gelir biliyorsunuz. (Speaker ZS: secular modernist group) You know what this means. 2. Bunun manası bir merkezden yönetilir. (Speaker NE: the conservative group) Uzum and Uzum Table 1 The distribution of borrowings according to the languages and the speakers Factors Focus of the factors Factor 1 Part of speech of the word Factor 2 Topic of the utterance Factor 3 Stress Factor 4 Position in the sentence Factor 5 Pauses Factor 6 The language of origin Factor 7 Speakers Factor 8 Area of utterance This means that it is organized from a single source. In sentence (1), the speaker-ZS uses a Turkish-origin word which means (meaning); whereas NE uses an Arabic word, though there is a Turkish equivalent to give the same meaning. These two words co-exist in contemporary Turkish language with varying degrees of frequency. In this example, the borrowed word is a noun. There are also other instances with verbs, adjectives, and adverbs. In this data set, nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs are sampled for statistical analysis. Table 3 shows the distribution of Turkish and borrowed words according to the structure of the token. As Table 3 illustrates, nouns have the greatest frequency (N=154) in this dataset and shows a similar distribution in the categories of borrowed (N=78) and Turkish-origin (N= 76) words. The second-most frequent part of speech is the verbs (N=52). The use of Turkish-origin verbs is observed in 46 tokens, while a borrowed verb is used only six times. In the category of adjectives and adverbs, there is also a similar distribution between borrowed (N=8) and Turkish-origin (N=10) words. Another variable is the topic of the speech in which the token is analyzed. Table 4 shows the topics included in this analysis. As can be seen from Table 4, the most common topic of speech is politics (N=187), followed by history (N=23), business and economy (N=13), and religion (N=3). There are Fig. 1 The scattergram of probability of application/nonapplication The Historical and Linguistic Analysis of Turkish Politician Table 2 The frequency of Turkish-origin and borrowed words The use of Turkish words The use of borrowed words Total 58.8% (N=93) 41.2% (N=133) 100% (N=226) not significant differences among the categories in terms of the use of borrowed or Turkishorigin words. However, the greatest difference can be observed within the categories of business and economy, religion, and politics. The following variable is the phonological variable to investigate whether the speakers stress the word they borrow. Table 5 shows the frequency of borrowed and Turkish-origin words according to the stress (stress, no stress) made on the token word. As could be seen from Table 5, the instances of stress on the token word (N=31), are significantly less than no stress instances (N=195). The speakers stressed on the token word more, when it is a borrowed word (N=19), than when it is a Turkish-origin word (N=12). In addition to the phonological variables that might have influenced the onlineborrowing, the position of the word in the sentence (beginning, middle, end) is analyzed. Table 6 shows the distribution of tokens according to the position of the word. As shown in Table 6, most of the token words are located in the middle of the sentence (N=196), very few of them are positioned at the beginning (N=13), or at the end of the sentence (N=17). When the token word is at the beginning of the sentence, it can be either a borrowed word (N=6) or a Turkish origin word (N=7). The token words in the middle of the sentence are generally in Turkish (N=112) and less frequently in other languages (N= 84). When the token word is at the end of the sentence, where the verb is located in Turkish, it tends to be in Turkish-origin (N=14) rather than other languages (N=3). This could be explained with the fact that Turkish is a verb-final language, and most of the borrowings are in the noun category as shown in Table 3, whereas it is less often in the verb category. Another phonological variable that might have influenced the online-borrowing is the pauses that take place before or after the token word. Table 7 shows the distribution of the token words according to the preceding and following pauses. As Table 7 shows, there are 20 instances of preceding pauses. Speakers paused (more than 2 s) before a borrowed word (N= 15), and a Turkish-origin word (N= 5). While the following pauses are more often after a Turkish-origin word (N= 14) than a borrowed word (N =8), most of the tokens do not indicate any pause before or after a token word (N= 184). One of the most significant factors in this study is the language from which the online borrowings are made. Speakers mix words from different languages such as Arabic, Persian, French, English, etc. in their speech. Although these words exist in the Modern Table 3 The distribution of tokens according to the part of speech Nouns Borrowed Verbs Adjectives and adverbs Turkish Total Borrowed Turkish Total Borrowed Turkish Total 50.6% 49.4% 70.8% 11.5% 88.5% 23% 42.9% 57.1% 6.2% N=78 N=76 N=154 N=6 N=46 N=52 N=8 N=10 N=14 Uzum and Uzum Table 4 The frequency of borrowed and Turkish-origin words according to the topic Religion Borrowed Politics Turkish History Borrowed Turkish Borrowed Business and economy Turkish Borrowed Turkish 66.7% 33.3% 40.6% 59.4% 47.8% 52.2% 30.8% 69.2% N=2 N=1 N=76 N=111 N=11 N=12 N=4 N=9 Turkish Dictionary (2005), they actually have their Turkish-origin equivalents which coexist with the borrowed ones. Table 8 shows the distribution of tokens according to the languages. Figure 2 shows the visual illustration of the distribution of tokens according to the languages of origin and the speakers. According to the findings shown in Table 8, Islamic conservative group speakers have the tendency to use Arabic-origin words (42.4%) almost as often as Turkish-origin ones (48.4%). Turkish nationalist group speakers show a preference to use Turkish origin words (63.4%) more than other languages. Secular modernist group speakers show a similar pattern to the latter exhibiting a tendency to use Turkish origin words (78.2%) more often than the borrowed words. According to these findings Arabic is the most common code to borrow lexical items from; whereas, borrowings from Persian, French, and other languages are not as frequent in this dataset. Another significant factor which is hypothesized to influence the online-borrowings, is the political orientation of the speaker. As mentioned in the previous section, speakers are using the opportunity to have access to different codes within the same language. These codes have given hundreds of words to the Turkish language. However, these borrowed words were either modified with Turkish affixes or replaced by their Turkish equivalents during the language reform in 1928. Therefore, the speakers are making choices to choose Turkish origin words or borrowed ones. Thus, the speakers have the freedom to use different codes according to their political orientation or other possible variables which are out of the scope of this study. Table 9 shows how often the speakers do online borrowings during their speech. As can be seen from Table 9, there are no significant differences between the speakers in terms of the frequency they do online-borrowing. While the Islamic conservative speakers use borrowed words (N=43) slightly less often than Turkish-origin words (N=56), Turkish nationalist group speakers show a similar pattern with almost equal use of borrowed words (N=27) and Turkish origin (N=28) words. Unlike these two right wing groups, both the secular modernist group which includes the left-wing parties, show significant differences in terms of their preference for Turkish origin words (N=49), rather than borrowed words (N=23) in their speech. Table 5 The distribution of tokens according to stress Stress on the word Borrowed No stress on the word Turkish Borrowed Turkish 61.3% 38.7% 37.9% 62.1% N=19 N=12 N=74 N=121 The Historical and Linguistic Analysis of Turkish Politician Table 6 The distribution of tokens according to the position of the word in the sentence At the beginning In the middle Borrowed At the end of the sentence Borrowed Turkish Turkish Borrowed Turkish 46.2% 53.8% 42.9% 57.1% 17.6% 82.4% N=6 N=7 N=84 N=112 N=3 N=14 As the data were collected from the public speeches of the politicians, the speakers tended to refer to other political parties from time to time in their speech. When the speakers are talking about other political parties or their leaders, the pattern of their borrowing shows some interesting results which are briefly discussed in this paper. Table 10 shows the distribution of tokens according to the area of speech. The categories are: (1) general area, (2) conservative group, (3) nationalist group, and (4) secular-modernist group. According to the findings shown in Table 10, the speakers talked about general issues staying within a general area using more Turkish-origin words (N=43) than borrowed words (N=34). However, when they get out of the general area and start talking about other political leaders, the pattern of borrowing shows some differences which were identified through qualitative and quantitative methods of analysis. Most of the speakers made more references to the conservative group switching into their imaginary area. When the speakers from modernist and nationalist groups are within the area of the conservative group, they used slightly more Turkish words (N=72) than borrowed words (N=54). When the speakers are talking about the nationalist group, they are showing more preference for Turkish origin words (N=7) than borrowed words (N=2). In the case of secular-modernist group, there is also more preference for Turkish-origin words (N=11) than borrowed words (N=3). This study hypothesizes that the speakers create an imaginary area in which they reflect their identity through their preferences for Turkish origin or borrowed lexical items. While some of the speakers show a more obvious pattern which could also be detected through qualitative analysis, some can only be identified using statistical methods. In the sentence below (1), there is a sample transcription in which the speaker shifts from the general area and starts talking about another political leader, thus getting into his imaginary area and using the borrowings that this political leader is claimed to use more often. (1) Bu sorunların altından kalkamayan, bu sorunların altında ezilen ruh haliyle de bu sorunları kaldıramayacağını açık açık gösteren gösteren başbakanı 22 Temmuz’da evine göndereceksiniz, istirahat edecek. Tabi bugün yaşanan yolsuzlukların cezasini çekecek, hesap sorulacak. Bundan kimsenin şüphesi olmasın. (Italicized words are borrowed from Arabic). This speaker belongs to the secular-modernist group, and thus is normally using more Turkish-origin words (68.1%) than borrowed words (31.9%) in this data set. However, his Table 7 The distribution of the tokens according to the pauses Preceding Pause Borrowed Following Pause No pause Turkish Borrowed Turkish Borrowed Turkish 75% 25% 36.4% 63.6% 41.7% 58.3% N=15 N=5 N=8 N=14 N=75 N=109 Uzum and Uzum Table 8 The distribution of tokens according to the languages and the speakers Arabic Turkish Persian French Other Islamic conservatives 42.4% 48.4% 2.4% 4.8% 1.8% Turkish nationalists 25.2% 63.4% 5.6% 4% 1.6% Secular modernists 15.6% 78.2% 2.6% 4.3% 1.7% use of Arabic words shows a drastic increase when he enters into the imaginary area of the Islamic-conservative leader who tends to use more Arabic words in his speech. Another example (2) is from the speech of the Turkish nationalist leader who has a tendency to use borrowed words at 49% in this dataset. (2) Yoksa, aklını, inancını ve milli duygularını mı kaybettin? Avrupa bile ciddiyeti gördü. Peşmerge bile akıbetini fark etti. Sen hala kavramadın. (Italicized words are borrowed from Arabic). In sentences (1) and (2), the speakers address the islamist-conservative leader who was the former prime minister. The speakers address this leader like talking to him in person and ask him why he acted passively in national security issues as well as economic concerns. As can be seen in the statistical findings and the example sentences, there is a tendency to adapt to the addressed speaker’s area and style of speech. This study suggests evidence for the existence of an imaginary area in which a speaker reflects his identity, and the other speakers adapt to that once they are involved. This interesting finding will be investigated using a larger dataset in a subsequent study. Conclusion The above discussion shows that the main source for online lexical borrowings is linguistically structure of the word, and historically the language reform in 1928 and the linguistic diversity that followed. Linguistically speaking, speakers do most lexical borrowings in the category of nouns probably due to two facts: (1) the grammatical structure of Turkish is different from Arabic, Persian, and French, which makes it less likely to fit a borrowed verb into a Turkish sentence; (2) these nouns represent some concepts that came into the language long ago with its language attached. Historically speaking, although these words were replaced with their Turkish equivalents in 1928, some speakers still show Fig. 2 The bar graph illustration of the tokens according to languages of origin and the speakers Distribution Among Languages Percentages 90 80 DB Nationalist 70 ZS Modernist-Secular 60 NE Religious-Conservative 50 40 30 20 10 0 Arabic Turkish Persian Languages French Other The Historical and Linguistic Analysis of Turkish Politician Table 9 The frequency of borrowings according to the speakers Islamic conservatives Borrowed Turkish nationalists Turkish Borrowed Secular modernists Turkish Borrowed Turkish 43.4% 56.6% 49.1% 50.9% 31.9% 68.1% N=43 N=56 N=27 N=28 N=23 N=49 preference to use them as evidenced with the descriptive findings above. The speakers do online lexical borrowings from the languages they associate with their political orientation. These findings are parallel to the assertion of Balim (1996): The more conservative or religious press and authors abstain from using Western terminology and stay within the rules of a more conservative word order, strictly subjectobject-verb. However, the majority of Turkish authors seek to use Turkish words…the language now reflects the more pluralistic identity of Turkey and Turkish culture. (p.112) Applying this insight to the current study and merging it with the recent study of Bhatt (2008) which suggests a third space created with code mixing, it could be argued that the speakers in this study create an imaginary space for themselves in which they position themselves with regard to the associated community and the outside community. Other speakers/actors who trespass this area are also adapting themselves to this private area and follow the sociolinguistic pattern of the owner. The imaginary space, in which the speakers negotiate their identities and participate in the meaning making process through political speech, is undoubtedly built at the nexus of history and linguistics as the analysis of current study attempted to evidence. The findings presented in this paper are in the direction to support the assertion that sociolinguistic patterns reflect and transport social and political changes. This notion is also reflected in the seminal work of Trudgill (2002). Due to a recently reformed society, the ongoing process of modernization in Turkey seems to coincide with the resistance from more conservative grounds. The power relations between these political groups take several forms and are observed in several aspects of life. The same play has been performed on the same stage with different actors since the language reform in 1928. Having been established with modernist goals and started by a secular government in 1923, Turkey has seen different groups of leaders with different political orientations over the past 85 years. Given the fact that historical and political changes are inevitably mirrored in sociolinguistic changes, Turkey and Turkish language is going through another process of change due to the current conservative government as well as its future integration into the European Union. Further studies could investigate the sociolinguistic change in the society led by major historical events, political leaders, or the attitudes of society towards these leaders with respect to the current sociopolitical conjuncture. Table 10 The distribution of tokens according to the area of speech General area Conservative group Nationalist group Borrowed Borrowed Turkish Secular modernist Borrowed Turkish Turkish Borrowed Turkish 44.2% 55.8% 42.9% 57% 22.2% 77.8% 21.4% 78.6% N=34 N=43 N=54 N=72 N=2 N=7 N=3 N=11 Uzum and Uzum References Abu Haidar, F. (1996). Turkish as a marker of ethnic identity and religious affiliation. In Y. Suleiman (Ed.), Language and identity in the Middle East and North Africa (pp. 117–133). Richmond: Curzon. Amara, H. M. (1996). Hebrew and English borrowings in Palestinian Arabic in Israel: A sociolinguistic study in lexical integration and diffusion. In Y. Suleiman (Ed.), Language and Society in the Middle East and North Africa. London: Curzon. Amara, M., & Spolsky, B. (1996). The Construction of Identity in a divided Palestinian village: Sociolinguistic evidence. In Y. Suleiman (Ed.), Language and identity in the Middle East and North Africa (pp. 81–100). Richmond: Curzon. Association, T. L. (2005). Modern Turkish Dictionary, 2005, Retrieved on September 22, 2010 from http:// tdk.org.tr/TR/Genel/BelgeGoster.aspx?F6E10F8892433CFFAAF6AA849816B2EFB40 CE59E171C629F. Aydıngün, A., & Aydıngün, İ. (2004). The role of language in the formation of Turkish National Identity and Turkishness. Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, 10, 415–432. Ayturk, I. (2004). Turkish Linguists against the West: The Origins of Linguistic Nationalism in Atatürk’s Turkey. Middle Eastern Studies, 40(6), 1–25. Balim, C. (1996). Turkish as a symbol of survival and identity in Bulgaria and Turkey. In Y. Suleiman (Ed.), Language and identity in the Middle East and Africa (pp. 101–117). Richmond: Curzon. Bear, J. M. (1985). Historical factors influencing attitudes towards foreign language learning in Turkey. Journal of Human Sciences of Middle East Technical University, 1, 27–36. Bhatt, M. R. (2008). In other words: Language mixing, identity representations, and third space. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 12(2), 177–200. Cuceoglu, D., & Slobin, D. (1980). Effects of Turkish language reform on person perception. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 11(3), 297–326. Johnstone, B. (2000). Qualitative methods in sociolinguistics. New York: Oxford University Press. Özen, Ö. F. (2003, January 5). Dil Yarası: Dog-Shop [Language Fault: Dog Shop] Cumhuriyet. Retrieved on February 8, 2007 from http://www.dilimdilim.com/icerik/makaleler/dil_yarasi.htm. Trudgill, P. (2002). Sociolinguistics variation and change. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. Williams, G. (1992). Sociolinguistics: A Sociological Critique. London: Routledge.