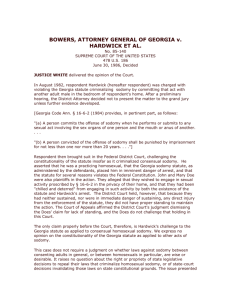

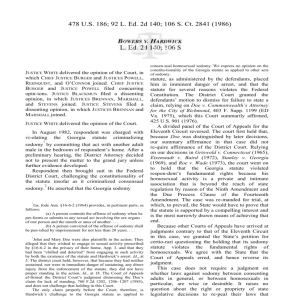

Bowers v. Hardwick: The Invasion of Homosexuals' Right of Privacy

advertisement