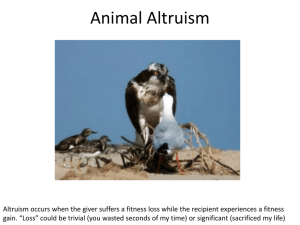

Advantageous Altruism - Rutgers Business School

advertisement