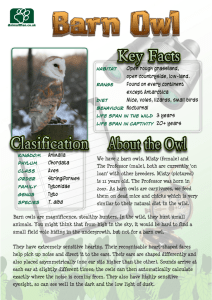

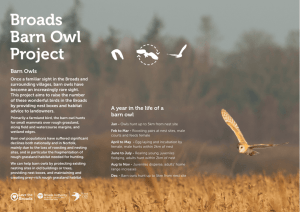

draft national recovery plan for the barn owl and its habitat

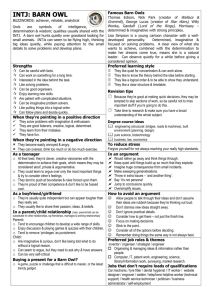

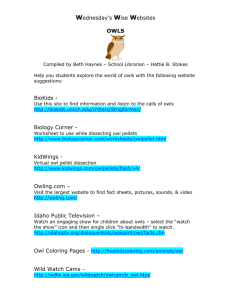

advertisement